AMERICAN WOMEN'S HISTORY INITIATIVE

LGBTQ Women Who Made History

In celebration of Pride Month, we honor LGBTQ women who have made remarkable contributions to the nation and helped advance equality in fields as diverse as medicine and the dramatic arts. Here are a few of their stories, represented by objects in the Smithsonian collections.

When actor/comedian Ellen DeGeneres played the first gay lead character on American network television in the 1990s, she not only broke a barrier in entertainment, she broadened acceptance of LGBTQ people across the country. It was a pivotal moment in American cultural history that echoes today.

In celebration of Pride Month, we honor LGBTQ women who have made remarkable contributions to the nation and helped advance equality in fields as diverse as medicine and the dramatic arts. Here are a few of their stories, represented by objects in the Smithsonian collections.

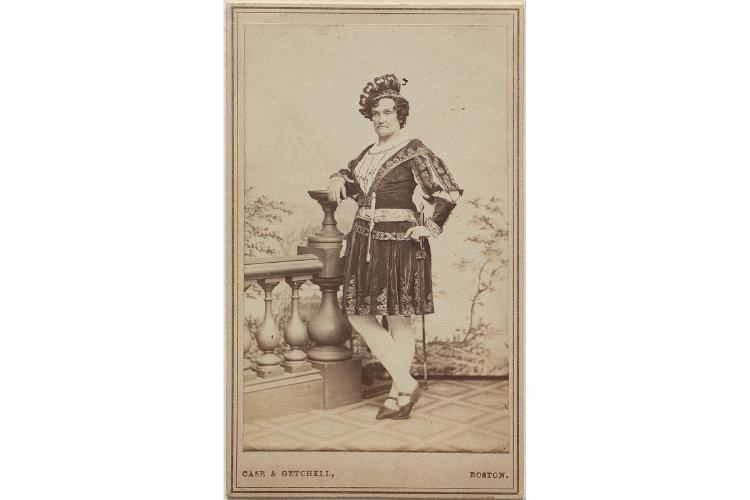

Charlotte Cushman was an icon of 19th century theatre, competing on equal footing with the greatest male actors of the age and winning a loyal following across the United States and Europe. While Cushman played both male and female roles, she was best known for her male roles including Romeo (pictured), Hamlet and Cardinal Wolsey. On stage and off, Cushman challenged conventions of gender and sexuality. In her adult life, she lived in a community of what she called "jolly female bachelors" or "emancipated women," known for producing art, wearing men's clothing, and lobbying for working women.

In 1997, actor and comedian Ellen DeGeneres sparked a national conversation on LGBTQ equality when her character on the ABC sitcom, Ellen, came out as gay—a first for network television. At the same time, DeGeneres came out in real life on the cover of TIME magazine with the memorable words, “Yep, I’m Gay.” Currently host of her own talk show, DeGeneres has won dozens of Emmy Awards and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2016.

Jane Addams wore many hats in the late 19th and early 20th centuries: suffragist, social worker, activist, Nobel Peace Prize recipient. But the work she led at Chicago’s Hull House ensured her legacy as one of America’s great social reformers. Addams founded the settlement house in 1889, when many new immigrants lived and worked in harsh conditions. Hull House provided health care, day care, education, vocational training, cultural and social activities, and legal aid to the immigrant community, creating a new model for social welfare.

This Dunlop tennis racket belonged to Dr. Renée Richards, ophthalmologist, former tennis player and one of the first professional athletes to identify as transgender. In 1976, following Richards’ sex reassignment surgery, the U.S Tennis Association required her to undergo genetic screening to play at the U.S. Open as a woman. Richards refused and was barred from the tournament. She then sued the U.S. Tennis Association for gender discrimination and won in a landmark decision. The following year, Richards was admitted to play in U.S. Open, where she reached the final of the women’s doubles.

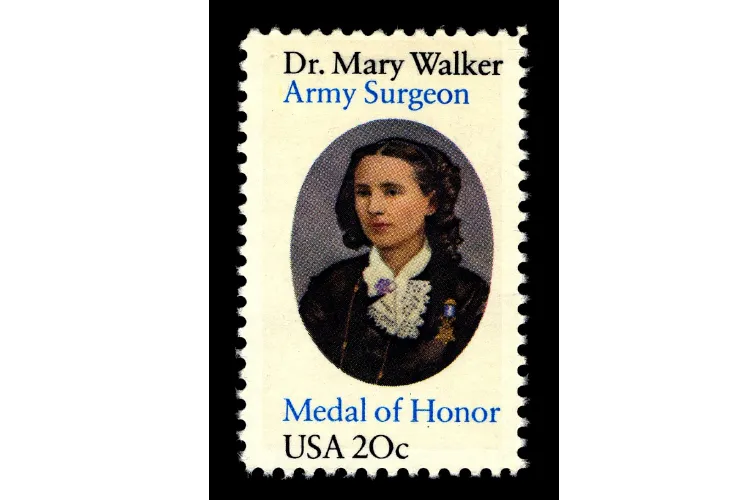

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, commemorated in this 1982 U.S. postage stamp, earned her medical degree from Syracuse Medical College in 1855. At the beginning of the Civil War, she offered her services to the government as a physician but was unable to obtain an appointment due to gender discrimination. She subsequently accepted a volunteer position as an Army surgeon and worked in field hospitals throughout the war, treating both Union and Confederate soldiers.

Astronaut Sally K. Ride wore this in-flight suit during the six-day STS-7 Space Shuttle mission aboard Challenger in June 1983, when she became the first American woman—and the youngest, at age 32—to travel in space. Later in life, Dr. Ride, also an engineer and physicist, became director of the California Space Institute and a professor of physics at the University of California, San Diego.

In 2013, President Obama posthumously honored Ride with a Presidential Medal of Freedom. “She inspired generations of young girls to reach for the stars and later fought tirelessly to help them get there by advocating for a greater focus on science and math in our schools,” he said. “Sally’s life showed us that there are no limits to what we can achieve.”

Alice Hamilton founded the field of occupational medicine at the turn of the 20th century. After earning her medical degree at the University of Michigan, she taught at Northwestern University and worked at Chicago’s Hull House, where she began investigating industrial workers’ illnesses. Hamilton was appointed to the Occupational Diseases Commission of Illinois, the nation’s first such investigative body. In 1919, Hamilton became the first woman to teach at Harvard Medical School. From 1924 to 1930, she served as the only woman member of the League of Nations Health Committee.

Sign Up to Join the American Women's History Community

You'll get the latest news, updates and more delivered directly to your inbox.

The Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative is supported in part thanks to people like you. Make a gift now and help us amplify women's voices, reach the next generation, and empower women everywhere.