Naming Ourselves: Asian American and Latina/o Arts Meet in the Kathy Vargas Papers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/collage1.jpg)

Photographer Kathy Vargas’ papers, in the collection of the Archives of American Art, not only contain valuable documentation of the Chicana/o art scene, but also unexpectedly holds traces of the active nineties Asian American arts community. Nestled between Vargas’ letters to art critics and newspaper clippings of exhibition reviews, the documents reveal a history of these two communities’ intersections through art.

Chicana/o identity encompasses pride in Mexican American culture and ethnicity. In the early nineties, Vargas’ work toured in the watershed exhibition Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation (CARA), which featured works by over one hundred Chicana/o artists. CARA set a strong precedence for other Chicano/a exhibitions that followed by grounding artworks within the context of Chicana/o culture, politics, and history. In 1992, Vargas also participated in the group show The Chicano Codices. In the catalogue for the exhibition, Marcos Sanchez-Tranquilino describes how Chicano/a art concerned itself with investigating its indigenous and colonial roots:

The Chicano art movement, which began with the Chicano civil rights movement in the mid-1960s, established aesthetic structures for examining and understanding the interconnections between historical events and artistic interpretation of those events. Ultimately The Chicano Codices acknowledges the national community of Chicano artists who explore, analyze, and evaluate the processes of historical reconstruction as they pursue personal and collective representation within an expanded definition of American art.

Early in her career, Vargas served as the Visual Arts Director of the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center in San Antonio, Texas. While the center’s mission focuses on Chicano/a, Latino/a, and Native American arts and culture, in 1992, the Guadalupe mounted the exhibition (en)Gendered Visions: Race, Gender and Sexuality in Asian American Art. The exhibition was curated by prominent Asian American art historian Margo Machida, author of Unsettled Visions: Contemporary Asian American Artists and the Social Imaginary. In her curatorial statement, Machida stresses how important it was for the center to provide the space for this particular show:

Hopefully, exhibitions like this will serve as catalysts for dialogue by suggesting that, in the construction of conceptions of self, unique visual vocabularies are being invented that allow Asian Americans—like all groups excluded or ignored by dominant culture—to “name” themselves in a society that offers few precedents capable of engaging the complexity of their experience.

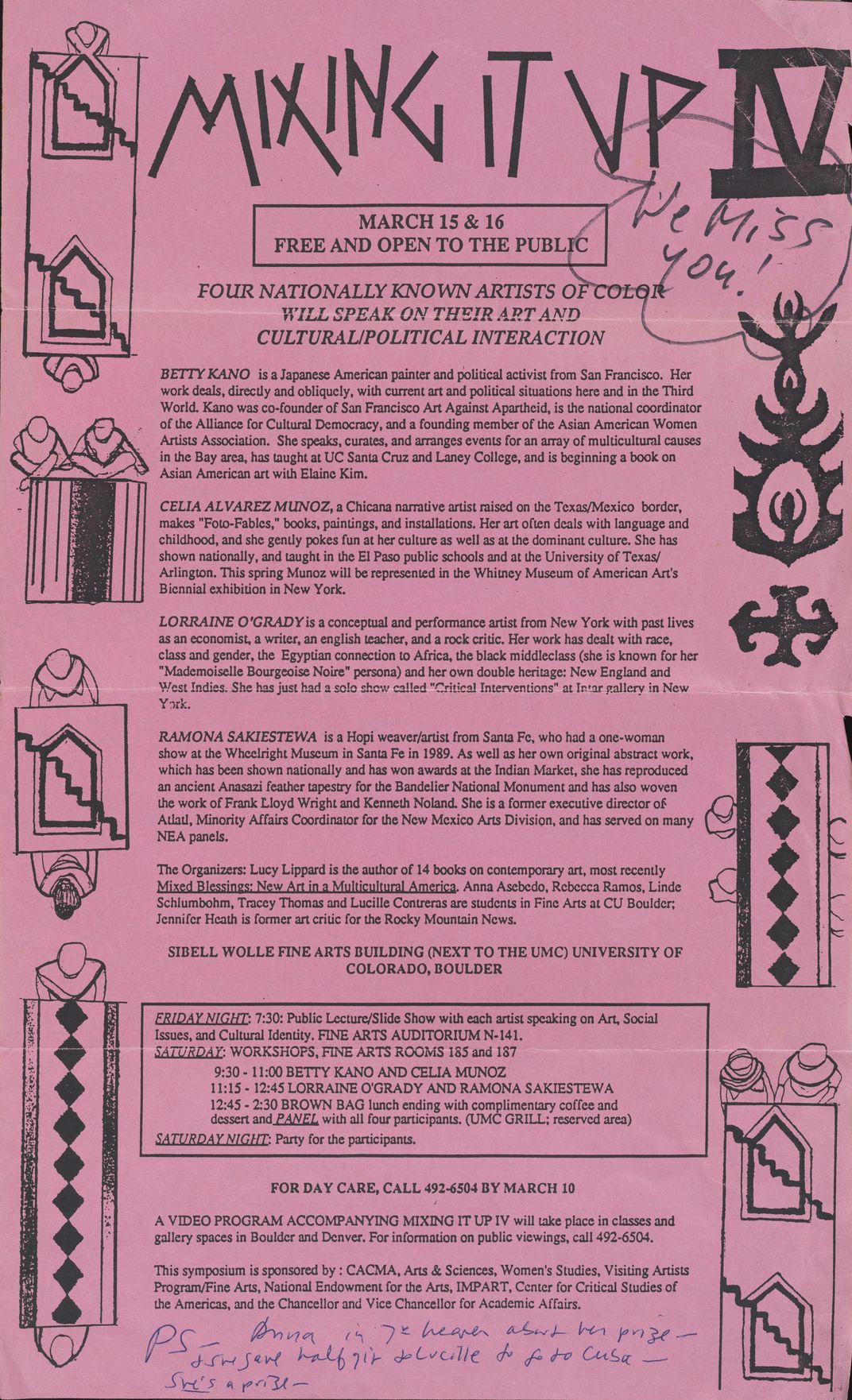

The Unsettled Visions exhibition brochure is one of many examples in Vargas’ papers that demonstrate how Asian American and Latino/a artists worked together to ensure that they could “name” themselves. For instance, the spring 1995 issue of Spot, the Houston Center for Photography’s biannual publication, featured two articles about Latino/a and Asian American art and identity alongside each other—“American Voices: Latino/Chicano/Hispanic Photography in the United States” and “Issues of Identity in Asian American Art.” Vargas’ papers also illustrate how Asian American and Latino/a artists worked in solidarity with other artists of color. Vargas’ close friend, critic Lucy Lippard, organized a three-day symposium, Mixing It Up IV, which revolved around a public lecture and programming about art and “cultural/political” interaction given by four women artists of color: Betty Kano, Celia Alvarez Munoz, Lorraine O’Grady, and Ramona Sakiestewa.

Vargas’ papers reflect how artists from different communities took interest in each other and the different intersecting issues that affected them. While Vargas is a respected figure in the Latino/a art scene, she also subscribed to Godzilla, an Asian American art network’s eponymous newsletter. The summer 1992 issue found in the Kathy Vargas papers features reviews and essays by prominent Asian American art figures: Byron Kim muses on how the Western art world’s privileging of form over content implicates artists of color; Paul Pfeiffer nuances discussions of LGBT issues within the art world by drawing attention to experiences of queerness that are differently racialized and classed; Kerri Sakamoto attempts to further contextualize Asian American positionality within the AIDS epidemic through her review of the group show Dismantling Invisibility: Asian & Pacific Islander Artists Respond to the AIDS Crises. In addition to becoming familiar with Asian American issues within the arts through Godzilla’s newsletter and intercommunity organizing, Vargas’ correspondence reveals that she was personally invited to shows by Asian American artists such as Hung Liu. The two artists exchanged catalogues and pictures, and Liu sent Vargas handwritten invitations to gallery openings for her shows such as “Bad Woman.”

The art histories of many underrepresented groups are lost and forgotten about within the The art histories of many underrepresented groups are lost and forgotten about within the mainstream art world when they are denied canonization. However, we see their cultural legacies and histories of intersectionality carried on today with art collectives such as Brooklyn-based By Us For Us (BUFU)— founded upon queer femme Black and Asian solidarity—and with group shows such as Shifting Movements: Art Inspired by the Life and Activism of Yuri Kochiyama at the SOMArts Cultural Center in San Francisco. This exhibition featured work by Asian American, Latina/o, and African American artists influenced by Yuri Kochiyama’s intersectional activism, guided by the philosophy to “build bridges, not walls.” The Kathy Vargas papers refuse erasure and contain valuable artifacts that testify not only to the strong history of these communities’ individual arts organizing and achievements, but also to the fact that these groups did not work in isolation but were intimately intertwined.

This post originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog.