Supercharged with Wit, Magic, and Talent: The Artists’ Soap Box Derbies

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/collage5.jpg)

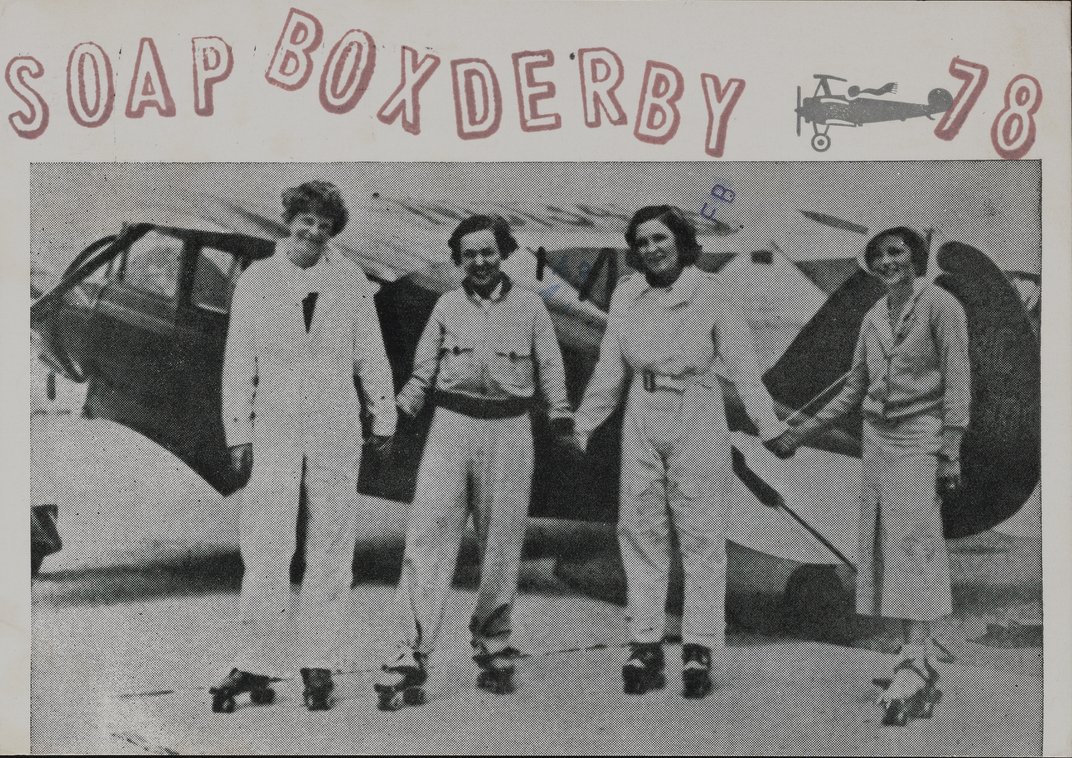

While on a walk one summer day in 1933, Myron Scott, the chief photographer for the Dayton Daily News, came upon a group of boys riding down a steep hill in makeshift cars they had fashioned out of old roller skate wheels and crates that had held peaches or soap, or any other materials they could cobble together. Watching them launch themselves down the hill in their homemade, gravity-propelled vehicles, he thought up the idea of holding a bona fide race and he asked the boys to come back the following week and bring friends. Nineteen boys turned up with their cars, and Scott took photographs and the idea of a sponsored race back to his editors. On August 19, 1933 the first soap box derby was held in Dayton, Ohio, with 362 drivers—including one girl, Alice Johnson, who came in second and stunned the crowd when she took off her helmet revealing her long hair—and forty thousand fans in the stands. By 1934 it was a national contest, the All-American Soap Box Derby, with thirty-four newspapers and the Chevrolet Motor Company serving as sponsors. Over the next several decades, the Derby would become a national obsession that, as writer Melanie Payne notes, showed “the effects of the Depression, World War II, the baby boom, the Civil Rights movement, and the rise of feminism.” But in 1975 and 1978, on sunny May days in a San Francisco park, the racetrack belonged to artists.

Billed as the “most unique” event ever produced by the San Francisco Museum of Art (SFMA), co-chairs Margy Boyd and Wally Goodman promised the Artists’ Soap Box Derby would be a race “supercharged with wit, talent, magic, and the honest sweat of nearly 100 Bay Area artists.” The idea for an artists’ derby was sparked by Ohio-born sculptor and painter Fletcher Benton as a fundraiser for the museum. Artists were recruited for the May 18, 1975 event to create original works of art in the form of cars or trophies—a few opted to do both—with an expense budget of $100 and $25 respectively. Seventy-nine artists built cars and thirty artists created award trophies in categories such as Most Amorphous, Fastest-Looking, Most Macabre, Most Literary, Best Pun, Most Bio-degradable, Funkiest, Most Joyful, Most Humane, Most Illusory, and The Booby Prize. Though the race was a non-competitive event, there were also awards for the three fastest cars.

Artists who created cars include Viola Frey, Clayton Bailey, and the counter-culture artist collective Ant Farm. Jo Hanson, Robert Arneson, Leo Valledor, and Ruth Asawa participated as trophy artists. A short documentary about the Derby by filmmaker Amanda Pope, The Incredible San Francisco Artists’ Soap Box Derby, surfaced online in 2007. The film opens with a shot of Dana Draper’s cycloptic orb covered in thousands of shiny copper pennies—aptly titled for the year 1975, Runaway Inflation—taking a downhill curve in McLaren Park where the race was held.

Also featured is Dorcas Moulton’s entry Moulton’s Edible Special—a replica of a classic English Morgan kitted out with freshly baked bread, which was immediately devoured by spectators as soon it rolled across the finish line. Other food-inspired cars took to the hill as well: a giant box of animal crackers, a Volkswagen Beetle made of chocolate, and a giant banana on wheels.

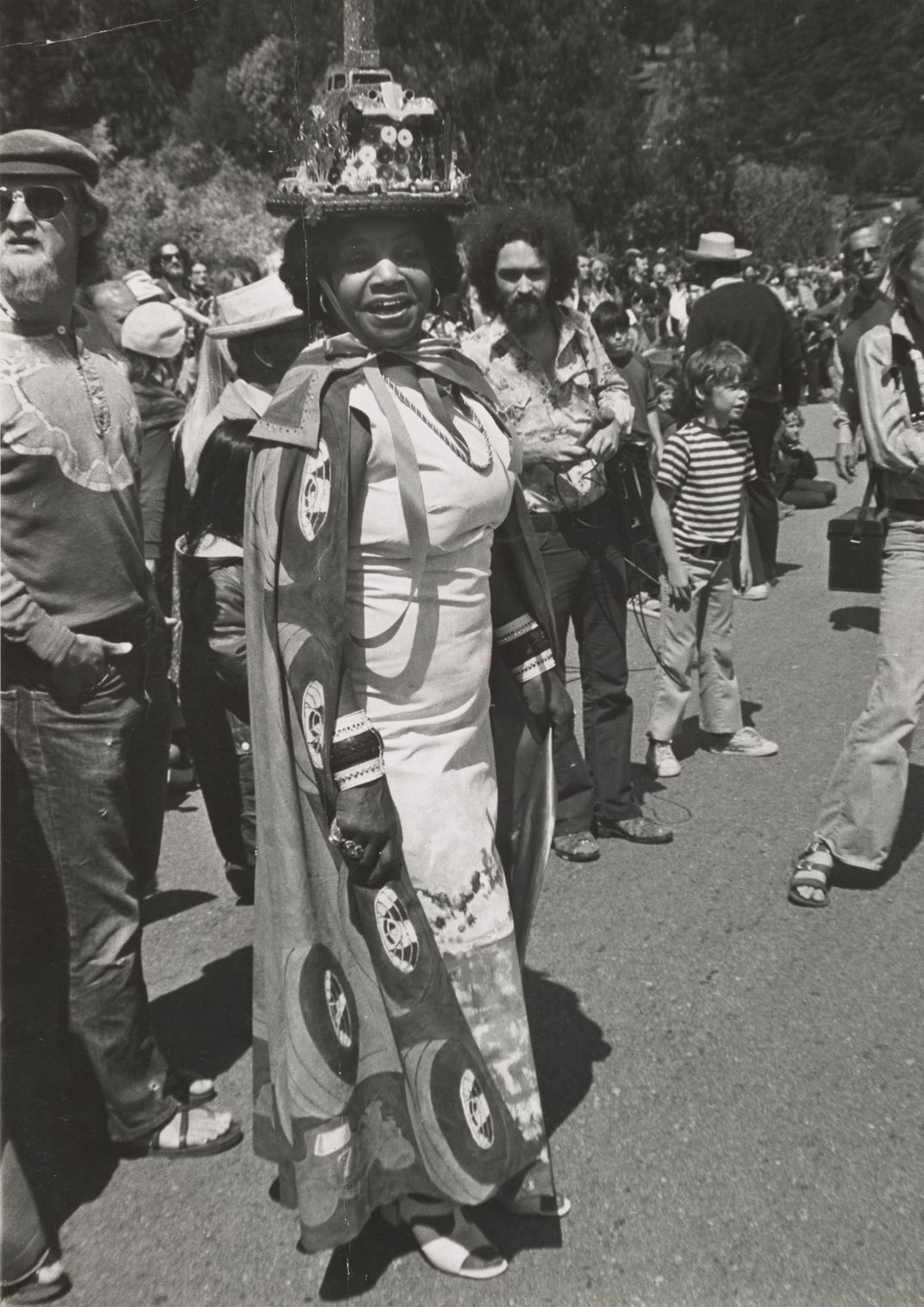

The day even included a derby queen, artists’ model Florence Allen. Having posed for such artists as Elmer Bischoff, Diego Rivera, Joan Brown, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and Mark Rothko, and often described as “San Francisco’s most famous artists’ model,” she was the natural choice to fill this role. Fiber artist K. Lee Manuel designed her jewel-toned costume, which featured a cape covered in stylized wheels and a black and white checkered flag. Topped off with a kitschy, glitter-covered car, miniature palm trees, and colorful cars racing around the brim, Allen's crown, secured under her chin with a pink satin bow, sparkled in the sunshine.

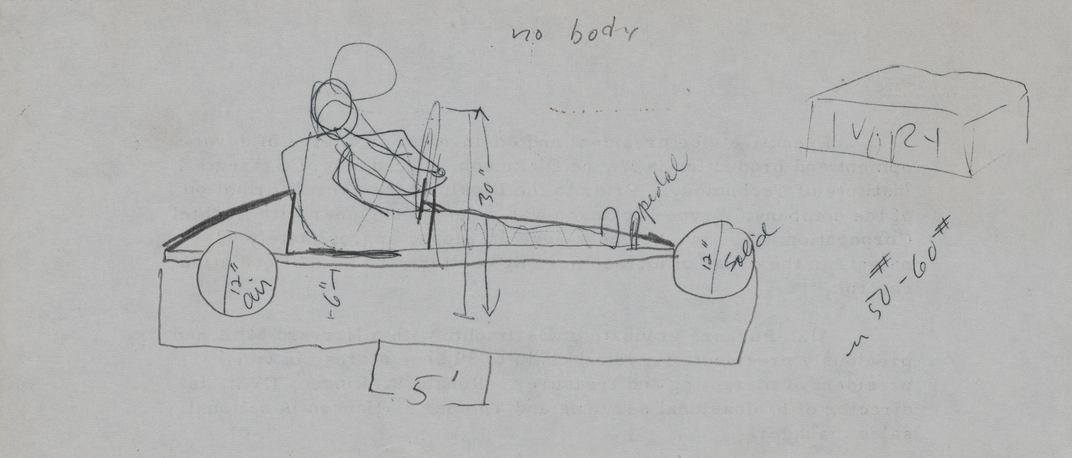

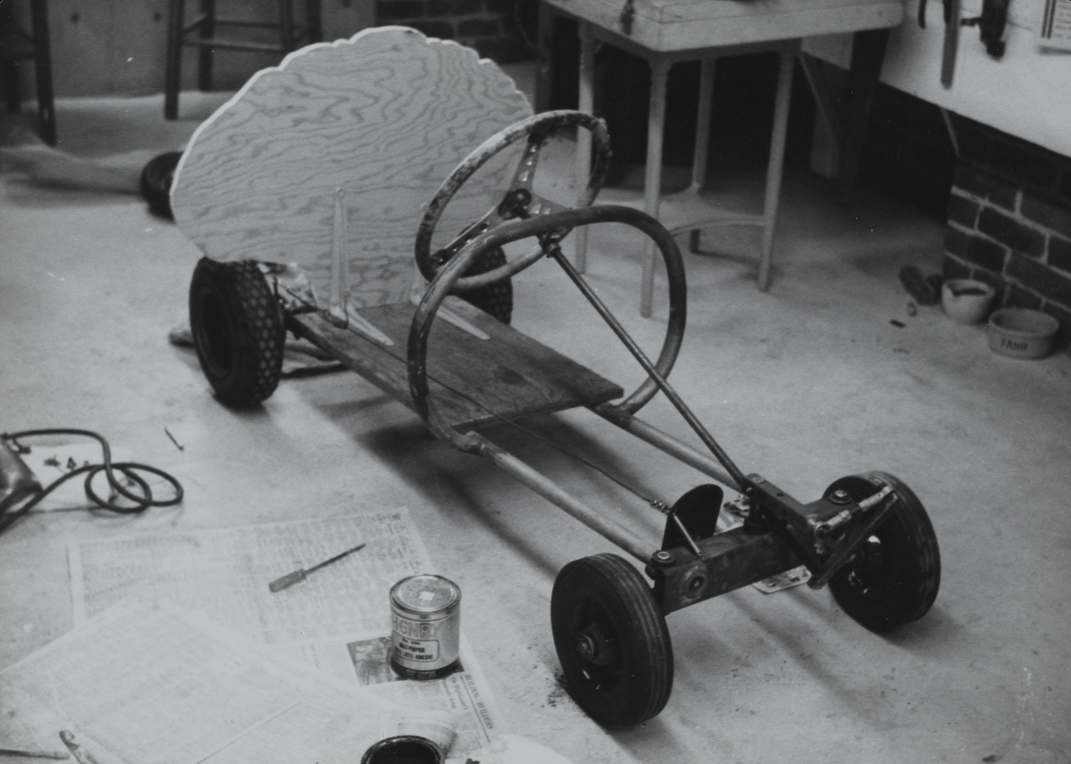

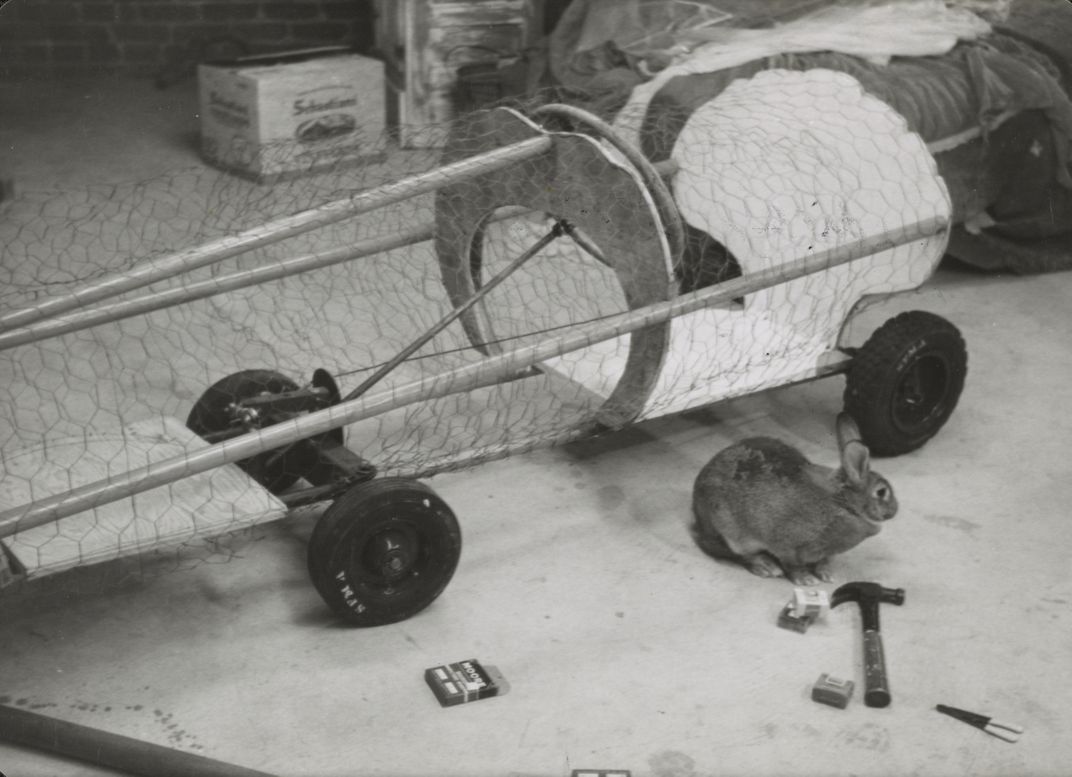

However, the car that grabbed my interest was created by Eleanor Dickinson. She is seen forty-five seconds into Pope’s film being wheeled by her husband Wade to the starting line in her entry, a giant tongue. The Archives holds Dickinson’s papers, where I found material on the Derbies. In the file for the 1975 race are correspondence and press releases from the museum, notes and schematic drawings of her car, and photographs documenting the construction of the car from frame to finish. A list of potential titles for the car includes well-known phrases such as Slip of the tongue, On the tip of my tongue, and Bite your tongue. In an email to me, Dickinson’s daughter Katy wrote that the car was ultimately called Tongue-tied and that her father likely did the engineering design.

Dickinson was a competitor in the second Derby held on May 21, 1978—also held in McLaren Park but now under the auspices of the re-named San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). This time in a contraption best described by the artist herself in a letter to public television station KQED, where she donated her car after the race for a fundraising auction:

The car is called “Model T”, is a modified 1934 Ford chassis with pipes etc. bolted to the top and painted bright colors like a Rube Goldberg sculpture (Citroen designed the chassis). The donation does not include the stuffed skunk, the live 8' python, or the five nude models on top (tho’ possible publicity of the same may help your auction!).

It is not a surprise that Dickinson created an entry on the subject of artists’ models; they were central to her work as both an artist and educator. On the subject teaching figure drawing, she told me via email in 2013 that the “models always posed nude, which upset some students who had never seen a very elderly person nude—or one very fat or scarred . . . but I thought it was a very important aspect of dealing honestly and well with the human form.” Dickinson frequently filmed interviews with those who modeled for her, which she compiled in a 1977 documentary The Models. A later iteration of the film from 1985, Artists’ Models of San Francisco, includes color footage of Model T taking the hill. One of Dickinson’s favorite models, Katy Allen, who was an active member and president of the San Francisco Models’ Guild, holds a prime seat at the front of the car. Four other models striking classical poses, a python named Gideon, and the artist herself, driving but fully clothed in a red leotard, round out the ensemble. Katy Dickinson recalled that her mother “was so proud [of her Derby trophy] that she kept it in the front hall for many years.”

There are not any photographs documenting Dickinson’s 1978 car found in her papers, but the Archives of American Art does have a first-hand account of the day written by Jan Butterfield. In her essay, “Thrills, Chills and Spills — The Second Artist’s Soapbox Derby,” Butterfield provides a detailed description of Model T:

While nudity was not the order of the day—San Francisco’s often chill wind (which fortunately held off through the day) forestalled much of that—one entrant topped all others for its lack of costumery. Representing the local models guild, the car/float created by Eleanor Dickinson and sponsored by Forrest Jones, Inc., “unveiled” its attendants just before the starting signal was given—to reveal a 300 pound naked woman as the figurehead—whose mounds of quivering flesh shook with each bump as the car took off. Attending her were a topless black woman with a live boa constrictor, two naked men assuming classic sculptural poses, and variety of other activity—too much to be seen clearly at that speed, and all the more remarkable for it.

Butterfield’s eyewitness narrative also provides a thorough accounting of other cars in the race: A “‘Constructivist’ car designed by Matt Gill . . . topped with silver feelers and balloons” which was maneuvered down the hill via radio signal. The entry by Penelope Fried and Gary Lichtenstein, “an exquisite oriental fish in coral and yellow with soft painted scales an[d] a curvilinear tail with fushia [sic] tassels.” A giant Black Forest cake created by Barbara Spring “was literally a birthday cake, and the crowd was asked to sing ‘Happy Birthday to Loren,’ as it rolled by.”

Butterfield describes two standout human entries: An assemblage of “pigtailed girls in satin shorts, visors and rainbowed socks” dubbed the “East Bay All Stars” was sent down the hill by Ray Saunders, gripping a rope to maintain balance on the curves. And a creation by Bryan Rogers, Butterfield writes, brought “suspense and theater” to the day.

Halfway down the track [the car] stopped, the back door opened and eight giant paint tubes jumped out, followed by eight enormous brushes. The tops to the tubes were unscrewed, and ribbons of colored crepe paper spewed forth, and were carried up and down the track by the cavorting brushes. Bobbing and weaving, the human paint tubes—which comprised Rogers entire sculpture class from room 511 at San Francisco State, danced—to the delighted cheers of the crowd.

The crowd certainly expected something more than a beat up old peach crate, and they got it in McLaren Park.

The organizers proposed that the first Artists’ Soap Box Derby would be significant for “the enjoyment that everyone derives from the day, the bringing together of artists with themselves and with the general public. . . .” Contemporary newspaper accounts attest to the event’s success. Quotes from artists describe how the Derby brought the Bay Area art community together and inspired creativity among them. Artist David Best credited working on his car entries with setting his approach to art making in a new direction by allowing him to create something outside of the confines of “serious” art. Not that there weren’t any serious aspects to the day—as the organizers implored in a pre-event letter to race participants, “P.S. If you have a crash helmet, please bring it Derby Day.” But, among the thrills, chills, and spills, the Artists’ Soap Box Derbies were indeed supercharged with wit, talent, and magic.

This post originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog.