Udder Madness: One Artist’s Adventure with 4,000 Cows

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_dickelea_65758_sv.jpg)

Imagine you are out for a Sunday drive in the country. There is bucolic scenery all around: clear blue skies, rolling green pastures, sturdy red barns. And cows, lots of cows. Except, there is something strange about these cows. None of them are swatting flies with their tails or lackadaisically wandering through the field, lowering their heads to nibble on grass as it suits them. They are all very still and very skinny—too skinny—as thin as a piece of cardboard to be exact. Then you notice another peculiarity. Some of these cows are pink, purple, and red.

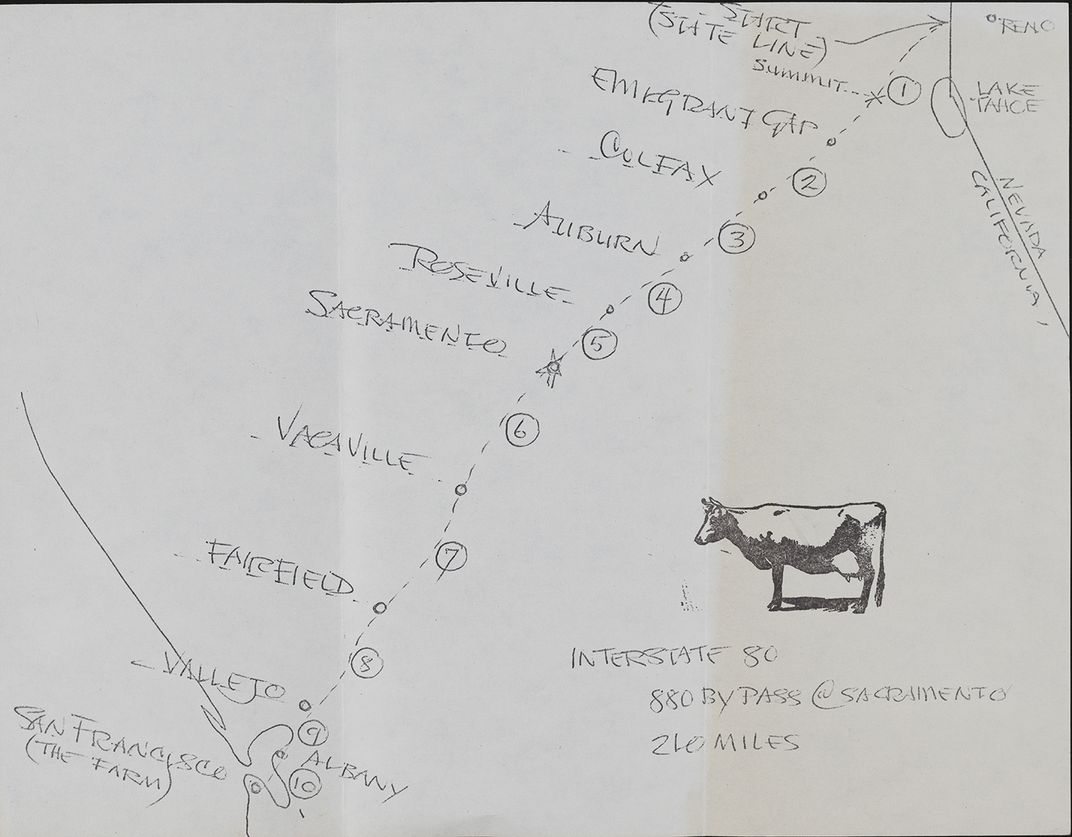

If you were traveling between Reno and San Francisco along Interstate 80 and the 880 North Sacramento Bypass on December 5, 1976, you would have come across many curious herds of cows. The Celebration of Wonder (COW) was a large-scale, one-day action conceived by artist Mel Henderson where 4,000 cardboard Holstein cows—half of the cutouts in standing or grazing shapes, and the other half the leftover silhouettes—were staked along a 205-mile route to “surprise and delight” passing motorists.

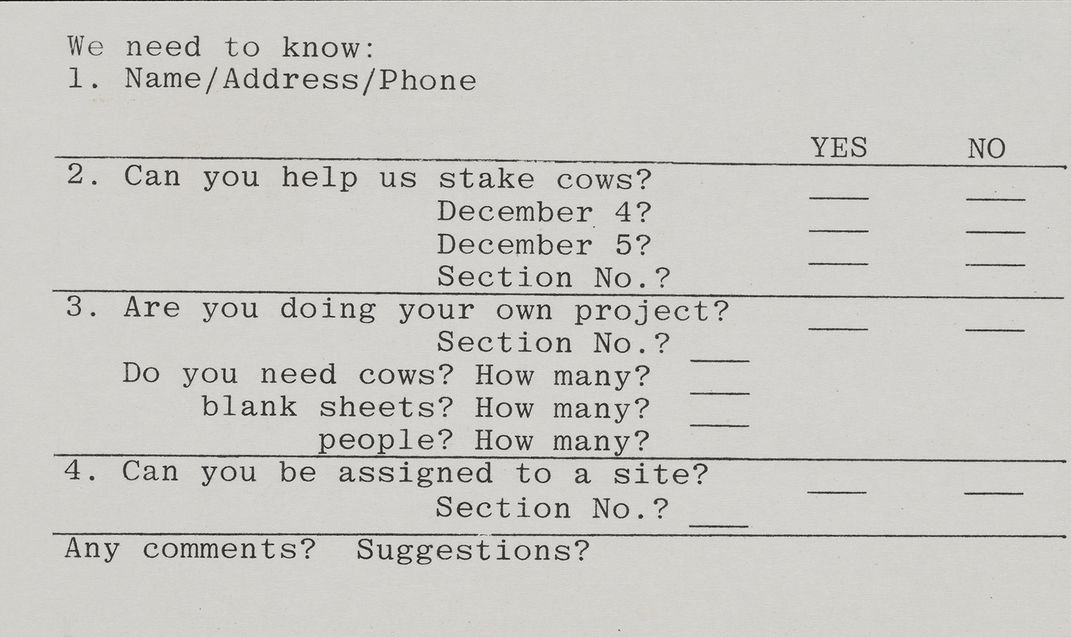

For all of its lightness, it was a serious and intricate undertaking which took nearly a full year of planning. A letter announcing the project was sent out on Christmas Day in 1975, and things were underway in earnest by mid-January. Henderson reached out to about fifty artists—including Eleanor Dickinson in whose papers this source material is found—to invite them to a planning meeting, and he charted a Greyhound bus that same month to select sites where “at intervals certain ideas or events will be presented depending on what is conceived by individuals or groups participating.” He also noted that “We can attempt the most absurd of ideas and should.”

The scope of the project required a large number of volunteers, so Henderson, a faculty member at San Francisco State University, coordinated with four other colleges and universities to bring in students. Initially he had planned to outsource the fabrication of the cows, but the costs were prohibitive so the volunteers took on the job. Sheets of cardboard measuring 67” x 87″ were cut out and painted. Doing this work “in-house” also meant the cows were easy to customize. Several, reportedly, wore Superman capes and at least one Holstein had a face with five eyes.

It is worth noting another well-known project that took place in Northern California the same year. While I have not found any evidence that COW was created as a response, Henderson’s cows were installed almost three months to the day after Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Running Fence snaked its way through roughly twenty-five miles of Sonoma and Marin counties for two weeks in September of 1976. Running Fence was a controversial and highly politicized piece. While the artists worked closely with fifty-nine ranch owners to obtain permission for Running Fence to be on their land, held multiple public hearings about the project, and produced an environmental impact report, they ran into trouble with the last 1000 feet of fencing which descended into the Pacific Ocean. Or rather, they ran afoul of the California Coastal Commission, which issued an injunction to stop the fence from being built on land under their jurisdiction. Christo and Jeanne-Claude went ahead anyway—The People v. Running Fence wasn’t even litigated until after the fence structure and white nylon cloth came down. As Robert Campbell wryly noted in the Boston Globe, it was “the first time anyone has ever made art out of the process of real estate development.”

Newspaper accounts about COW mentioned the timing of the two projects, but tended to focus more on its playful aspects, something the headline writers in particular reveled in: “The Non-Thundering Herd—A Cardboard Creation” came from the San Francisco Chronicle, while the Los Angeles Times declared, “Udder Madness on Interstate 80.” In the New York Times, John Brandon Albright conjured up the nonsense poet Gelett Burgess by quoting some of his best-known lines: “I never saw a purple cow, I never hope to see one; but I can tell you anyhow, I’d rather see than be one.”

In a planning letter sent to COW participants a month before the action would take place, Henderson laid out the ultimate vision for the action.

As [the observers] travel along, they will be greeted by more and more recognizably flat cows placed in simple lines or patterns or arrangements. Cow tableaux. Children undoubtedly will immediately enter into the game of “what’s next?” “where?” and “I would put one there!”

While some of Mel Henderson’s most important projects were large-scale actions investigating issues around prison reform, the environment, and peace, a sense of wonder also informed his work. As Tanya Zimbardo writes, “As a veteran for peace, he made several antiwar works over his lifetime as well as more playful expressions of the right to peaceful assembly.” With COW, Henderson demonstrated that it is possible to have an artistic practice rooted in serious engagement with the world, even while delighting in the absurd.

The exhibition Off the Beaten Track: A Road Trip through the Archives of American Art is on view through June 3, 2018 in the Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery at the Donald W. Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture (8th and F Streets NW, Washington, DC). Admission is free.

This post originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog.