Love Letters to Michigan

:focal(519x337:520x338)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_saaralin_11386_defaultA.jpg)

“With all the love that keeps flooding the air between New York and Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, it is surprising that planes can get through!”

–Letter from Aline Louchheim to Eero Saarinen, 1953

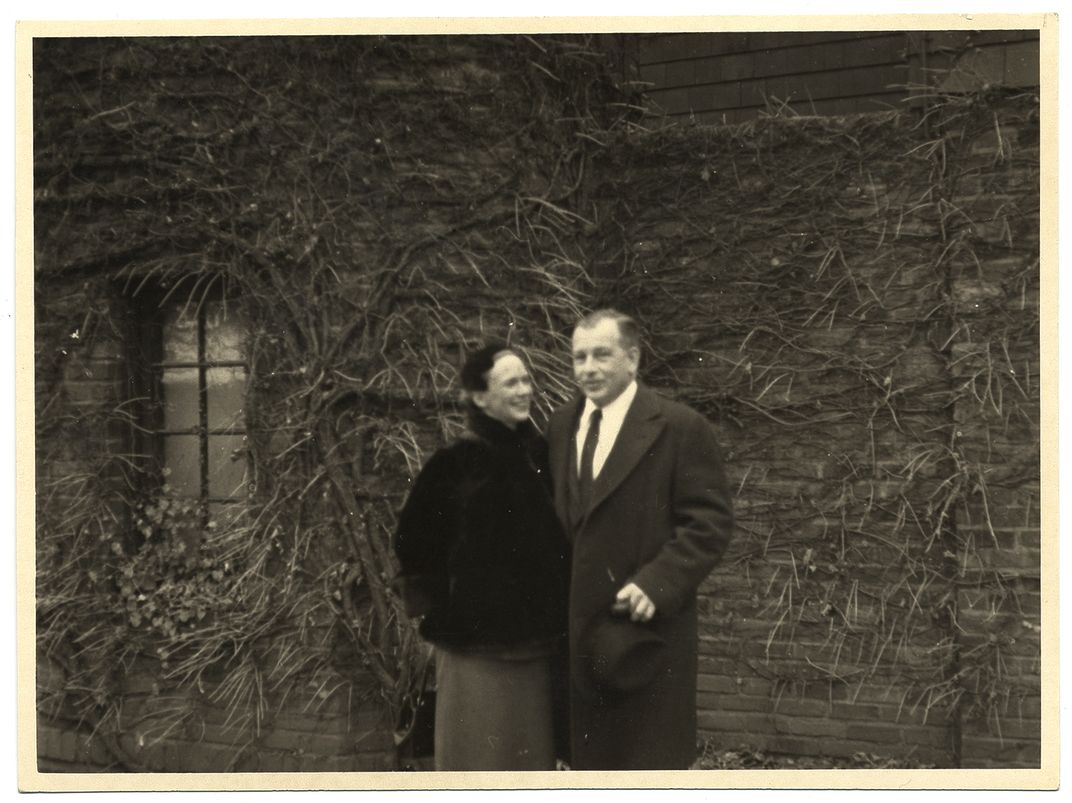

In January of 1953, writer Aline Louchheim was dispatched to Bloomfield Hills, Michigan by the New York Times Magazine to interview architect Eero Saarinen for a profile she was writing on him. Surprising them both, they fell for each other at first sight. By the time the piece ran on April 26, they were months into a secret affair. On February 8 the following year, Aline Louchheim became Aline Saarinen. While Eero’s hectic travel schedule provided opportunities for meeting, and they spoke regularly on the telephone, living 500 miles apart by airplane meant their relationship also developed through letters. These letters establish Michigan as a place central to their love story.

Garnett McCoy, curator emeritus of the Archives, liked to describe the job of an archivist as “reading other people’s mail for a living.” The correspondence between Eero Saarinen and Aline Louchheim satisfies the voyeuristic impulse. These letters, chronicling every aspect of their burgeoning love affair from the passionate to the banal, are rich with the stuff of life. They are brimming with talk about work, gossip, family challenges, erotic longing, and, most especially, love—pet names and darlings are bountiful. All of it was undergirded with a deep respect Eero and Aline shared for the other’s intellect.

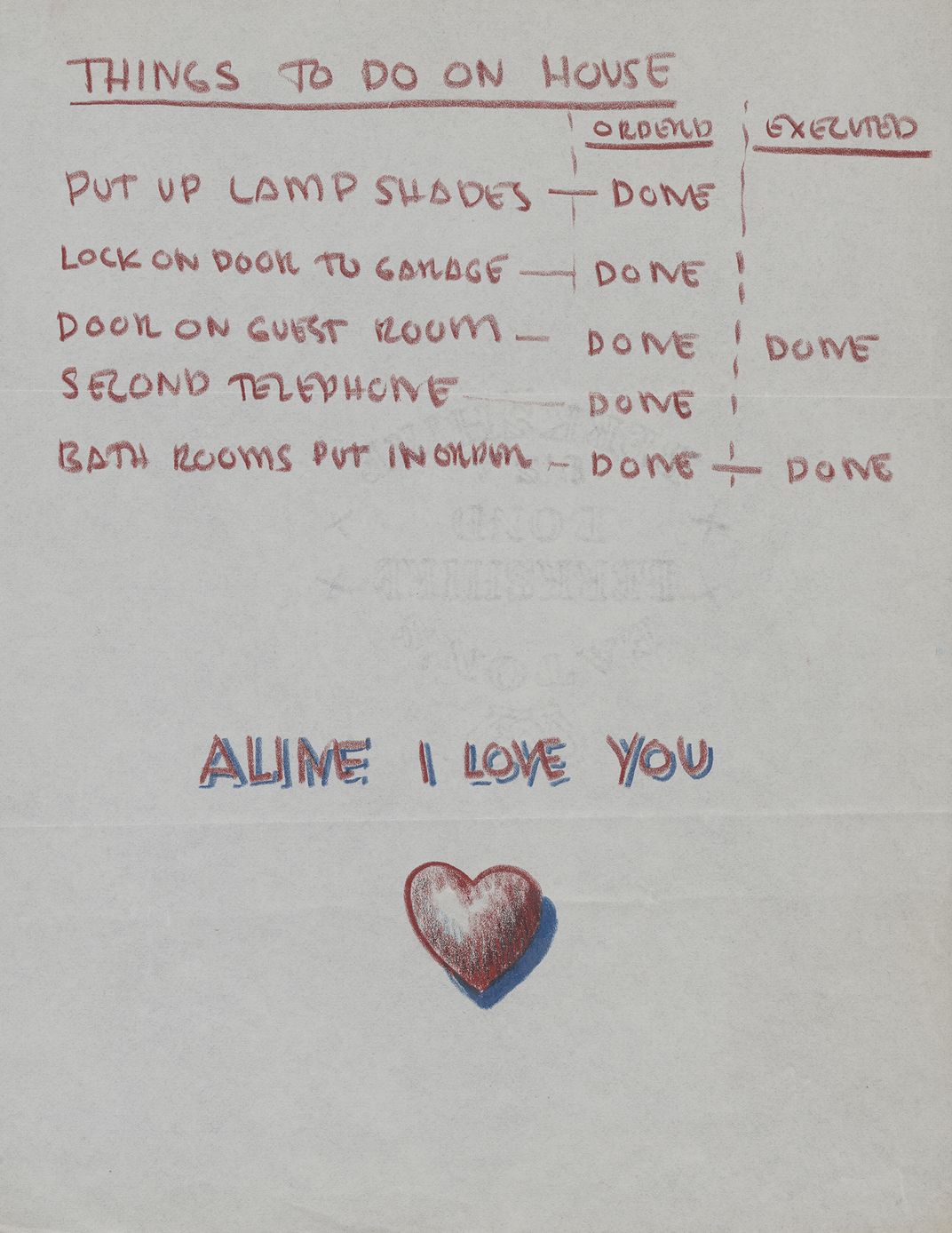

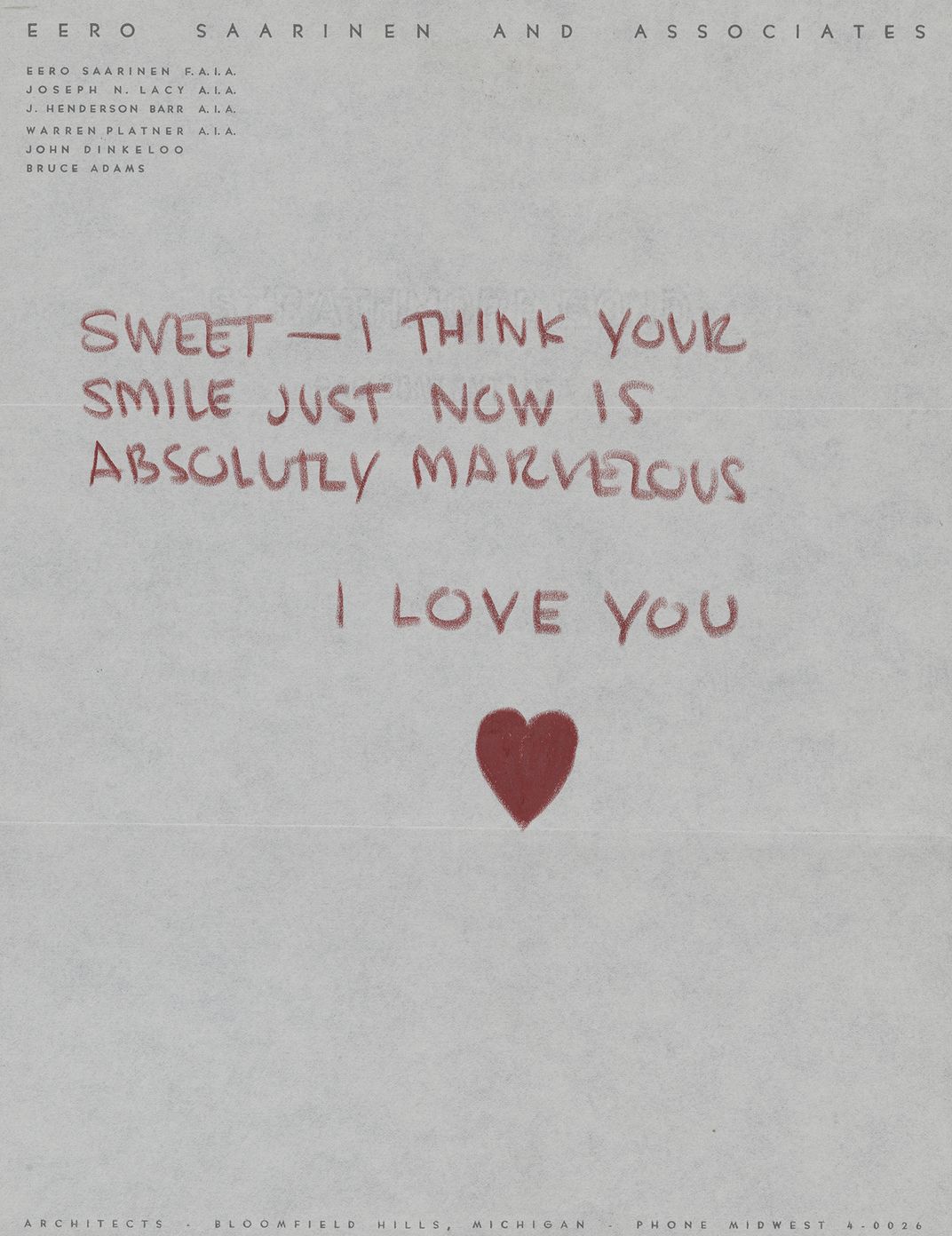

Reading through their letters, one gets to know the writers both as individuals and as a couple. Aline sometimes wrote essays (“First, I want to tell you what I feel about what I might call arts and crafts”), and Eero was a chronic doodler who liked to compose letters in mirror writing and had a tendency to write in lists. Together they developed their own shorthand and quirks of language: a line across the page bounded by cartoonish hands stood in for an embrace, and Eero often wrote, “I love you terribly much.” It is apparent that when they were apart, writing letters to each other was as much of a salve as receiving one.

Eero Saarinen and his family moved to the United States from Finland when he was twelve, and settled permanently in Michigan two years later. His father Eliel was the chief architect of the Cranbrook Academy of Art and first director of the school from 1932–1946. He continued to teach in the architecture department until 1950, and was also appointed a visiting professor of architecture at the University of Michigan. Eero’s mother Loja also taught in the fiber department, and his sister Pipsan was an instructor in the costume and interior design departments at Cranbrook. The family returned to Finland every summer until World War II, but Michigan became their home.

As an architect, Eero created designs that were both intimate (the “Grasshopper,” “Tulip,” and “Womb” chairs produced by Knoll and the Miller House in Columbus, Indiana), and expansive (the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, Missouri and the Trans World Airlines Terminal at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York). One of his most important projects was the General Motors (GM) Technical Center in Warren, Michigan, outside of Detroit.

Initially, General Motors was a project of Saarinen and Saarinen—father and son—before going dormant for several years. GM, later restarted the commission, this time putting Eero in charge of the when it was clear Eliel would not be able to complete the design. Eero has remarked that GM came to the Saarinens for “another Cranbrook,” meaning they wanted a compound that honored the individual needs of disparate departments within a unified environment. Ultimately, a center for cutting-edge technology, which assimilated modern architecture within humanistic surroundings, was created. Aline Louchheim wrote her article “Saarinen and Son” while the project was in mid-construction, noting, “in the huge 813-acre still unfinished General Motors Technical center the vastly complicated technical and engineering demands were scrupulously met. . . the buildings were made architecturally dramatic, expressing the exciting twentieth-century relationship among man, science, and industry.”

It was this same type of total environment that Eero Saarinen planned to bring to his design for the North Campus of the University of Michigan. Just as Aline sent news to Eero on her progress of her article, he often wrote to Aline about his own various projects, even while in their evolutionary stage. In one letter—currently on view in Off the Beaten Track: A Road Trip through the Archives of American Art—he shared, “the big push now is Michigan,” and included a sketch of his proposed design for the university’s School of Music. In his book Eero Saarinen, the first monograph on the architect to be published, Allan Temko lamented that

the largest single commission to follow General Motors—and comparable to it potential significance—was never carried out, to the real loss of American architecture. This was to have been a new north campus for the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, roughly the size of the old campus south of the Huron River, and devoted to the fine arts, engineering, and research. The master plan of 1953 shows an integration of buildings and spaces more richly compact than General Motors, on a more challenging site; and the square central plaza, descending in five terraced planes to a deeply set fountain, would have made a stirring civic space.

While Eero could not have known at the time, the School of Music was the only building from his project designs to be built. It is fitting that in a love letter to his future wife, he illustrated it with a sketch of the only building that was realized.

As their marriage approached, as well as Aline’s move to Bloomfield Hills, Aline and Eero’s letters sketched out plans for their new life together. There is a small cache of short love notes found in their papers—usually illustrated with a big red heart somewhere on the page—that I imagine Eero might have left on Aline’s desk for her to find. Aline, a lifelong New Yorker, made a home for herself in Michigan. While she continued to write for the New York Times, she also became the director of information service at Eero Saarinen and Associates. On September 19, 1964, at the dedication ceremony for the School of Music, Aline—along with Leonard Bernstein and Aaron Copeland—received an honorary degree from the University of Michigan.

In 1961 the Saarinens were preparing to move their family, which now included their young son Eames, and the Saarinen firm to Connecticut, but Michigan would be the last place they would live together. On August 21, Eero was diagnosed with an aggressive brain tumor. He died that September at University Hospital in Ann Arbor after complications from surgery.

Their time together as a couple was short, but from the start the Saarinens considered their relationship in terms of architecture and building. Aline wrote Eero in the early days of their romance,

. . .don’t feel that you ought to hold back any of your feelings—your doubts as well as your love. It’s all part of finding out what kind of a foundation it is—and if it’s to be a cathedral it ought to be a very beautiful one, one of your master works, on very firm foundations worthy of it. . . .We’ve been very good about no confused thinking at the start. What stage is this? Parti? My God, you’ve gotten me thinking in architecture!

Around the time they were married, Eero made a list in red pencil of twelve reasons he loved Aline. After accounting for everything from his admiration of her physical beauty to her organizational habits, he ended with, “XII The more one digs the foundations the more and more one finds the solidest of granit [sic] for you and I to build a life together upon.” And, they did.

The exhibition Off the Beaten Track: A Road Trip through the Archives of American Art is on view through June 3, 2018 in the Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery at the Donald W. Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture (8th and F Streets NW, Washington, DC). Admission is free.

This post originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog.