A Friendship in Letters: Miné Okubo and Kay Sekimachi

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_stockbob_62472_siv.jpg)

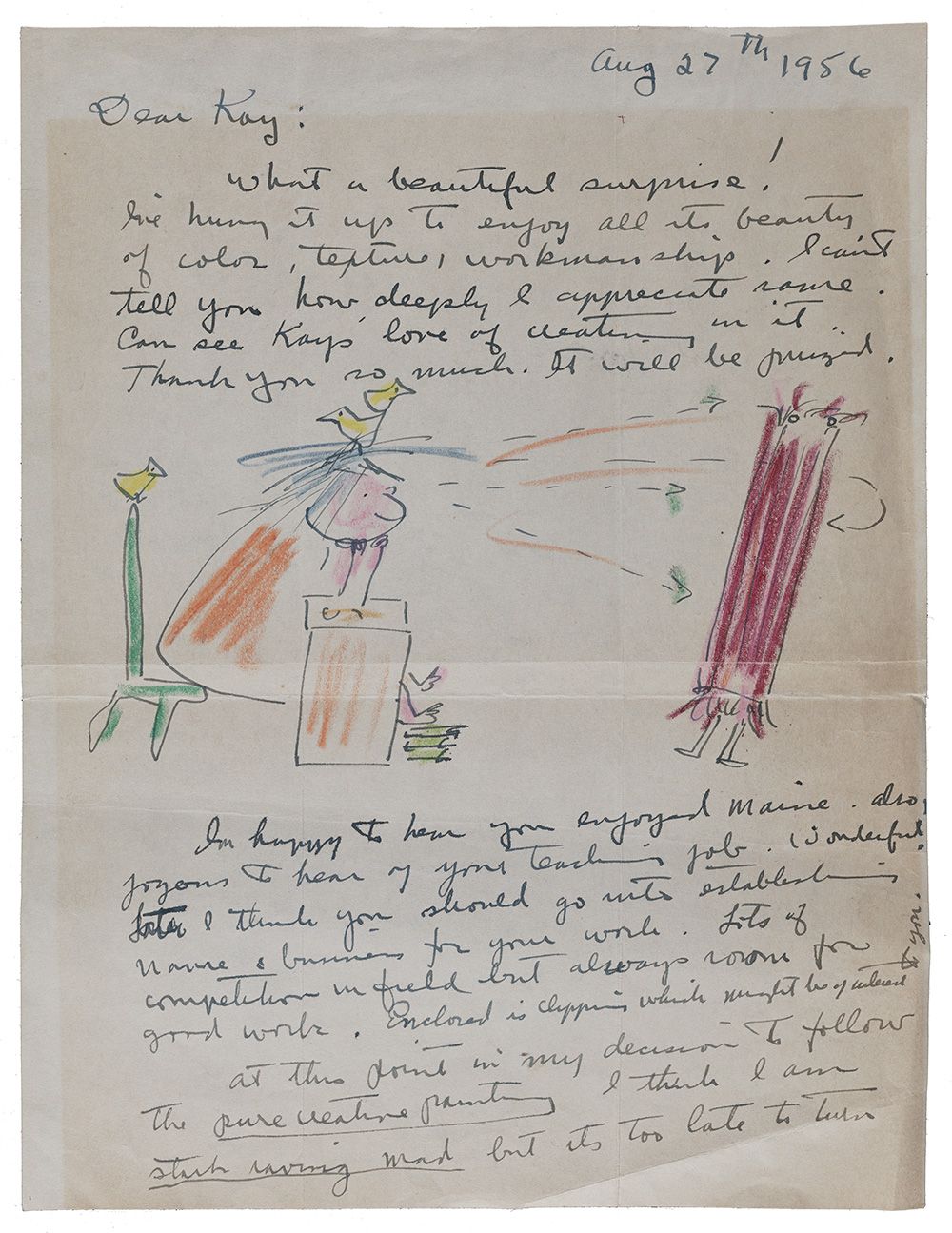

In a letter to Kay Sekimachi dated August 27, 1956, Miné Okubo wrote (grammar and emphasis Okubo’s own), “At this point in my decision to follow the pure creative painting I think I am stark raving mad but it’s too late to turn back for I’ve put too much into the fight.” Found in the Bob Stocksdale and Kay Sekimachi papers are several folders of letters from Okubo and they all reflect this fiery spirit and determination.

Kay Sekimachi and Miné Okubo met during World War II when they were both at Tanforan Assembly Center in California, before being relocated to the Topaz internment camp in Utah during roughly the same period (1942–1944). Okubo was already an accomplished artist before the internment, having received a bachelor’s and master’s degree from the University of California, Berkeley, and traveling to Europe on a fellowship where she studied under the painter Fernand Léger. Okubo, fourteen years older, taught art at the high school Sekimachi attended that was mostly run by internees inside the Topaz camp. They went separate ways after the war—Okubo to New York City to work for an issue of Fortune Magazine, Sekimachi to Ohio with her mother and sister before eventually settling in California—but they kept in touch. Both went on to become successful, prolific, and highly respected artists: Kay Sekimachi for her fiber art, Miné Okubo for her paintings and drawings. Their friendship which began during their time in the internment camp spanned more than five decades until Okubo’s death in 2001.

Over the years, the two frequently attended each other’s art exhibitions, offered feedback, exchanged art, and kept each other updated about their work. Okubo typically does not hold back. In an undated letter (circa 1956) she recalls seeing Sekimachi’s weaving in an unnamed show and remarks, “If I wasn’t looking for a ‘Sekimachi Masterpiece’ I would have never found this cut-off hallway off the 1st floor where your stuff is hung. . . . I liked the piece but felt the fuzzy wuzzy fringe distracted from the design. Too much chaos the way it was hung. It was hung loosely on rod and upper fringe was like rat’s nest.”

Okubo was an older and more established artist at the outset, her book Citizen 13660 about the internment camps was published in 1946, and her early letters are sprinkled with advice, “You and your sister can go into business together if she is going into commercial art. Lots of luck to both of you. Creative dreamers need lots of it to buck the tide of non-dreamers in this world” (August 27, 1956). As Sekimachi gets older and starts to exhibit more regularly the relationship transitions from that of student and teacher to colleagues.

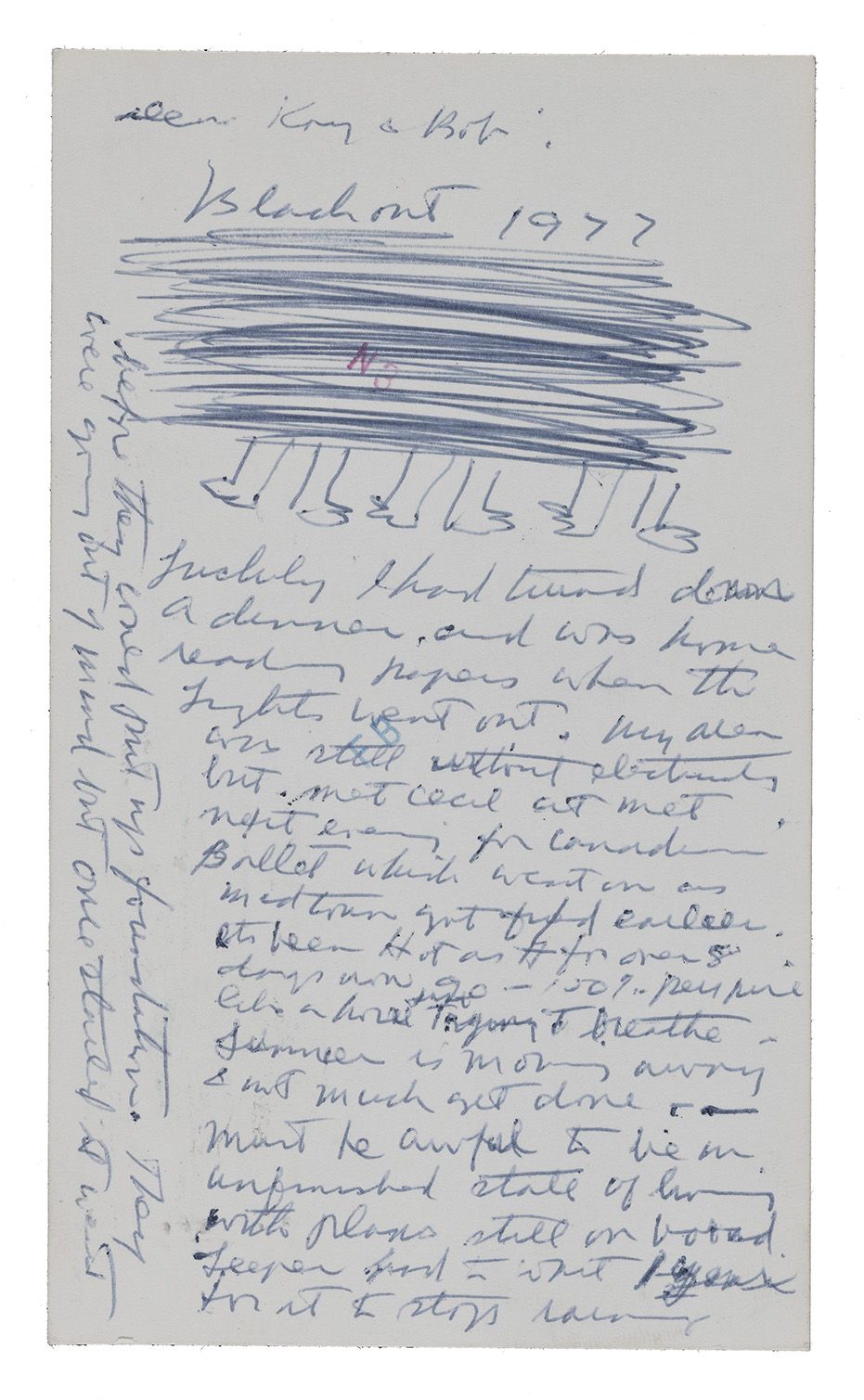

Okubo remains steadfast in her encouragement over the years, telling Sekimachi to keep going as she tries to make a living from her art. Although Sekimachi’s letters are not among the papers, Okubo must have relied upon her friend for support. By all accounts, Okubo had an austere lifestyle and lived in a small Greenwich Village apartment for years, and she often mentions troubles with her living situation such as quarrels with landlords and repeated break-ins at her apartment: in a letter dated December 30, 1971 Okubo wrote, “Kay, Holiday Season here in N.Y. is not exactly a Roman Holiday. … I tell you this place gets robbed all the time.” Another mentions a gaping hole was left in her wall and ceiling for a week while plumbers try to locate the source of a leak (March 9, circa 1971), and a cleverly illustrated postcard describes the New York City blackout of 1977 (July 22, 1977). Often the letters provide a portrait of New York City life that is as embattled and restive as Okubo’s personality.

Despite what must have been a difficult life for a young Japanese American woman living alone and working as an artist after the war, Okubo’s letters often have playful drawings of birds, cats, and rabbits; these imbue her writing with levity. Sometime around 1970 on September 8, she wrote, “I am glad you have cats—they sound real goofy and delightful. Cats alone know how to live because they maintain their personality and independence. They give one just enough for room and board and that’s that.” She was formidable, undaunted by challenges, and proud of her achievements and independence.

Nonetheless, comments about the fickleness of the public’s attention, the weather, health issues, and housing problems arise with increasing frequency in her letters beginning in the mid-1980s: “I have finally accepted the fact that I am alone on a total odds road on a universal values so it is my own challenge—picking up the pieces and now trying to build forward again. My generation gone so I will have to find imaginative ways of my own. It’s a hell road but I’m walking on—[illegible] eviction is a worry” (April 22, circa 1992).

At a glance, the word that I see over and over again in Okubo’s letters is “work.” In the final batch of letters from the mid to early 1990s, the word I see repeated often is “alone” and the phrase “my generation gone.” In a 1984 New Year’s greeting, Okubo expressed regret with having lost many friends over the years. The constant nature of her friendship with Sekimachi must have been invaluable.

In many ways, theirs is a unique friendship between two Japanese women who experienced the hardships of forced relocation and internment during World War II and shared a vision of becoming artists. The similarities aside, the letters provide a window into the lives of two people who saw each other through sickness and health, successes and disappointments, and shared the quotidian details of daily life, as friends do. The romantic image of artists struggling alone eclipses the fact that artists rely on support systems. Sekimachi viewed Okubo as a role model, but the help they offered each other must have been mutual. It was also lasting. After Sekimachi and her husband took a trip to New York City, Okubo wrote in a letter dated May 9, (circa 1984), “When we see friends we like it is as though time has not passed. It was good to see you both.”

This post originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog.