Acquisitions: Allan Frumkin Gallery Records

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_allafrum_65720_detailA_siv.jpg)

In the typescript of an undated essay titled “On Art Dealing,” Allan Frumkin (1927–2002) advised that “the dealer should love the artist,” but he or she should also be a “stern critic” who “help[s] the artist . . . realize himself and his art.” The records of the Allan Frumkin Gallery, which operated in Chicago (1952–1980; 1979–1980 as Frumkin & Struve) and New York City (1959–1995; 1988–1995 as Frumkin/Adams), offer multitudinous examples of how thoroughly Frumkin followed his own paternalistic advice. Approximately half of the thirty-four linear feet of papers is comprised of correspondence with gallery artists, a number of whom he gave a monthly stipend for many years. The remainder consists of artists’ files, financial records and sales correspondence, printed material, and photographs of artists, artwork, and gallery installations. In meaty letters to and from painters such as Joan Brown, Alberto Burri, Roberto Matta, and Peter Saul, Frumkin’s pursuit of a now vanished kind of artist-dealer relationship shines through.

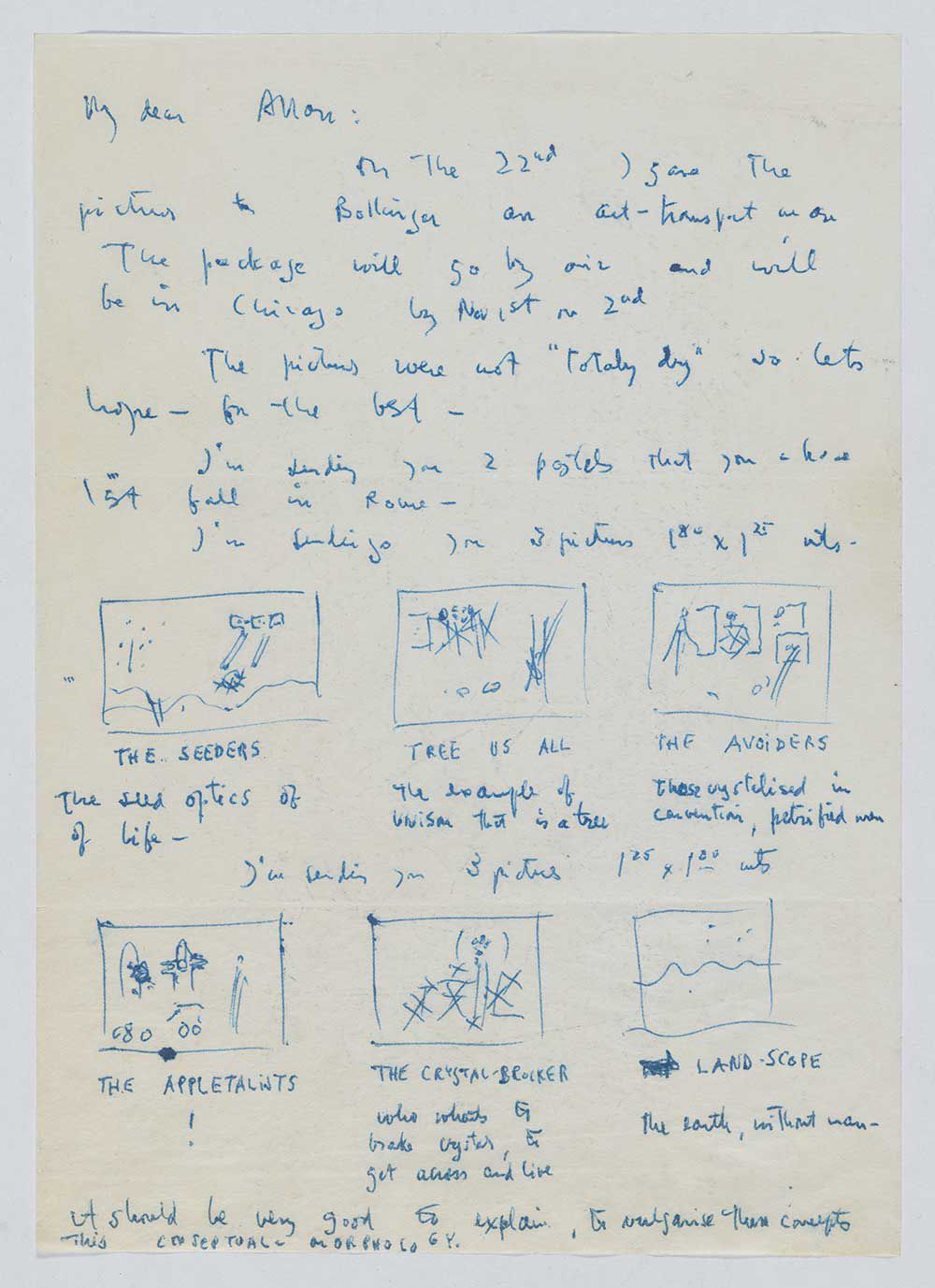

Frumkin’s main advisor, Chilean artist Matta, belonged to the international world of surrealism. “I think we will make a very good team,” Frumkin wrote to Matta in a December 1952 letter, confiding that taking down Matta’s first show at his Chicago gallery felt like “burying a dear friend.” Matta introduced Frumkin to the Italian artist Burri, whose work the dealer exhibited within his gallery’s first year of operation, along with that of Matta and Spanish-born Esteban Vicente. These Europeans helped contextualize the imaginative and often offbeat work of the American artists whom Frumkin increasingly folded into his exhibitions, including Saul, Louise Bourgeois, Joseph Cornell, Leon Golub, Red Grooms, June Leaf, and H. C. Westermann. He also mined California for artists previously unseen in Chicago and New York, including Brown, Roy De Forest, Richard Diebenkorn, Robert Hudson, and William T. Wiley. What emerged at the Frumkin Gallery was an aesthetic that contrasted sharply with the austere, mysterious abstractions of contemporaries such as Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt—a visual world in which surrealism’s dreams edged into idiosyncratic, parodic visions.

Beginning in 1976 Frumkin published a newsletter that offered well-written profiles of gallery artists in their studios, which were often far from urban centers. A full run of the thirty-one issue newsletter can be found in the records, along with drafts of articles, editorial comments, and mailing lists. In a brief history of the gallery, Frumkin’s wife and newsletter editor Jean Martin recalls that Frumkin “always followed closely the developments in the art world of his time, including the quick rise and fall of the East Village scene, the gradual decline of Soho, and the explosive rise of Chelsea.” Through each of these dramatic changes in the art world, Frumkin remained true to his instincts. “The art dealer who hasn’t the strength to maintain his own convictions . . . is lost,” Frumkin wrote in “On Art Dealing,” concluding, “The difficult and conflicting requirements involved suggest why a great art dealer is perhaps as rare as a great painter.”

This essay was originally published in the spring 2018 issue (vol. 57, no. 1) of the Archives of American Art Journal.