Fifty Ways to Use an Archive

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_macbgall_20725_SIV.jpg)

Years ago, as a student in American art, I kept coming across the same name over and over again: the Macbeth Gallery. I am even not sure when I first heard about it—perhaps reading about the gallery’s exhibition of “The Eight” in 1908 or while researching Maurice Prendergast, who had his first New York exhibition there in 1900—but as I continued my research on early twentieth century American art, the Macbeth references seemed to be everywhere.

From the seminar paper I wrote on Armory show organizer Arthur B. Davies to my qualifying paper in graduate school on Bryson Burroughs—painter, critic, and curator at the Metropolitan Museum from 1907 to 1934—everything led back to the Macbeth Gallery. Fortunately, I discovered that the Archives of American Art holds these records, which enabled me to delve deeper into my research. Not so fortunately, on my visits to the Archives, I repeatedly went down a rabbit hole enjoying unrelated letters from eager artists, needy collectors, and new museum directors, who counted on the gallery to send pictures for exhibitions. I was so delighted by these detours that I sometimes forgot to find the reference that I had come to look up.

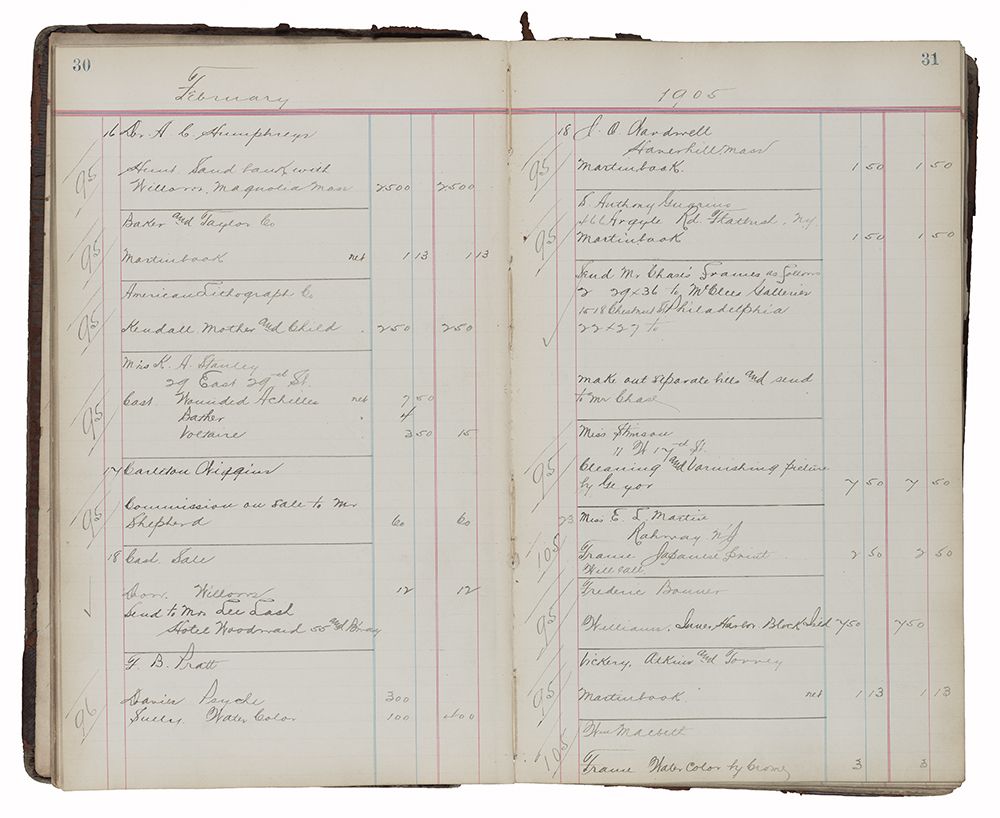

Based on this experience, I decided to focus my research on the gallery itself. What was its contribution? Was its role in American art truly as important as it appeared? With support from the Luce Foundation, I spent six months wrestling with the archive, trying to understand how it operated, putting early sales records in a database, scanning newspaper clippings in the scrapbooks, and reading letters and more letters from artists, writers, and critics, along with the gallery’s own periodical Art Notes, which promoted what was new in art and especially, of course, what was for sale at the Macbeth Gallery. I hired two talented graduate students, John Davis, then at Columbia University, and now Provost and Under Secretary for Museums, Education, and Research at the Smithsonian, and Debora Rindge, at the University of Maryland, who systematically made charts with summaries of the early correspondence and the scrapbooks.

Putting it all together, I gained a clearer picture of the world of art and commerce. My database of sales told me who was collecting art (and where) and how much they were paying. The correspondence demonstrated the gallery’s broad outreach to artists, collectors, critics, and museum directors nation-wide. Much, too, seemed to be happening behind the scenes as what was on view in the New York gallery, as noted in the scrapbooks, was not necessarily what was sold, as documented in the sales records. I had thought I would do an exhibition on the Macbeth Gallery—the best pictures they sold—but the real story, how the gallery operated and the context of the gallery scene, was far more interesting than simply their outstanding sales.

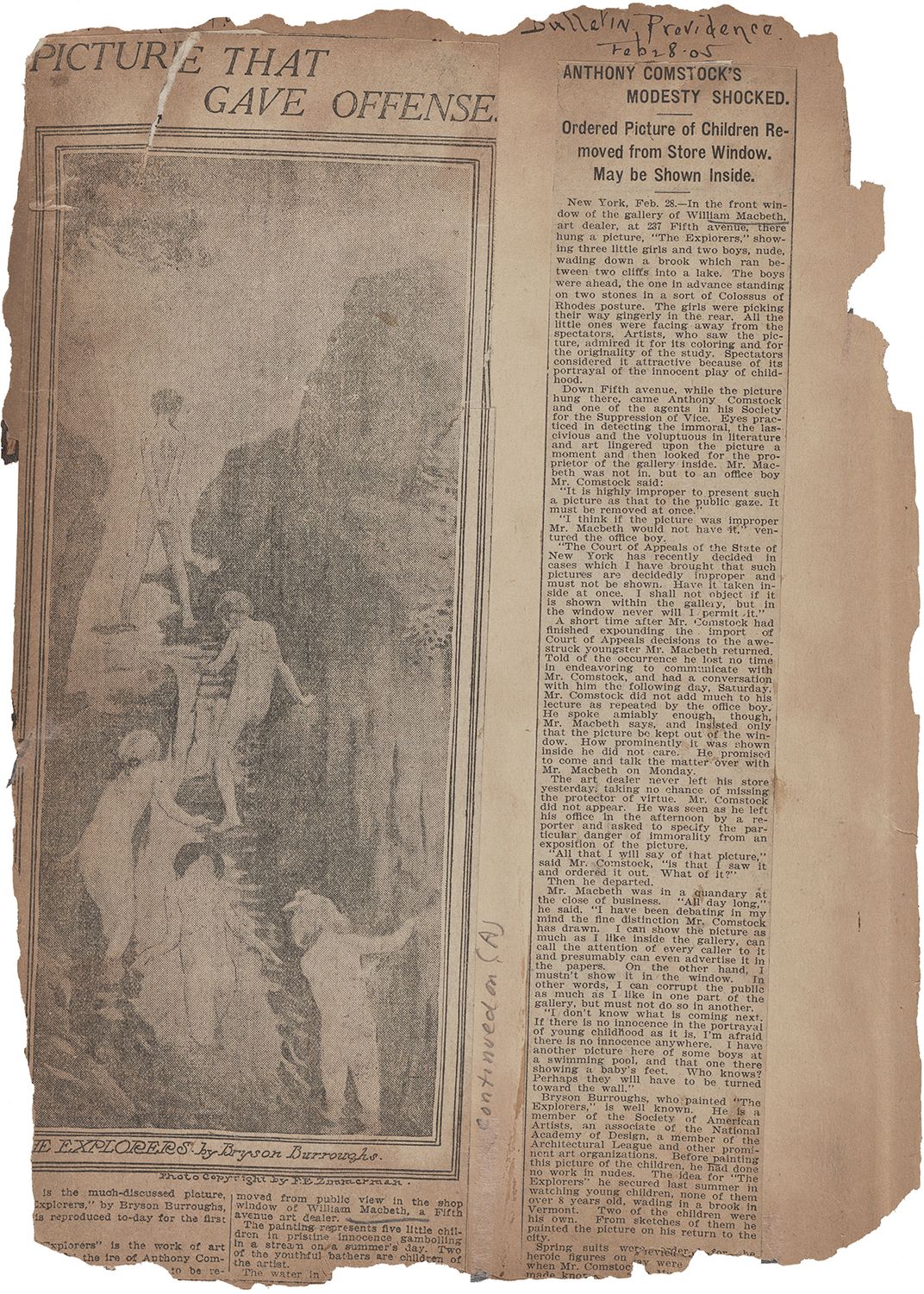

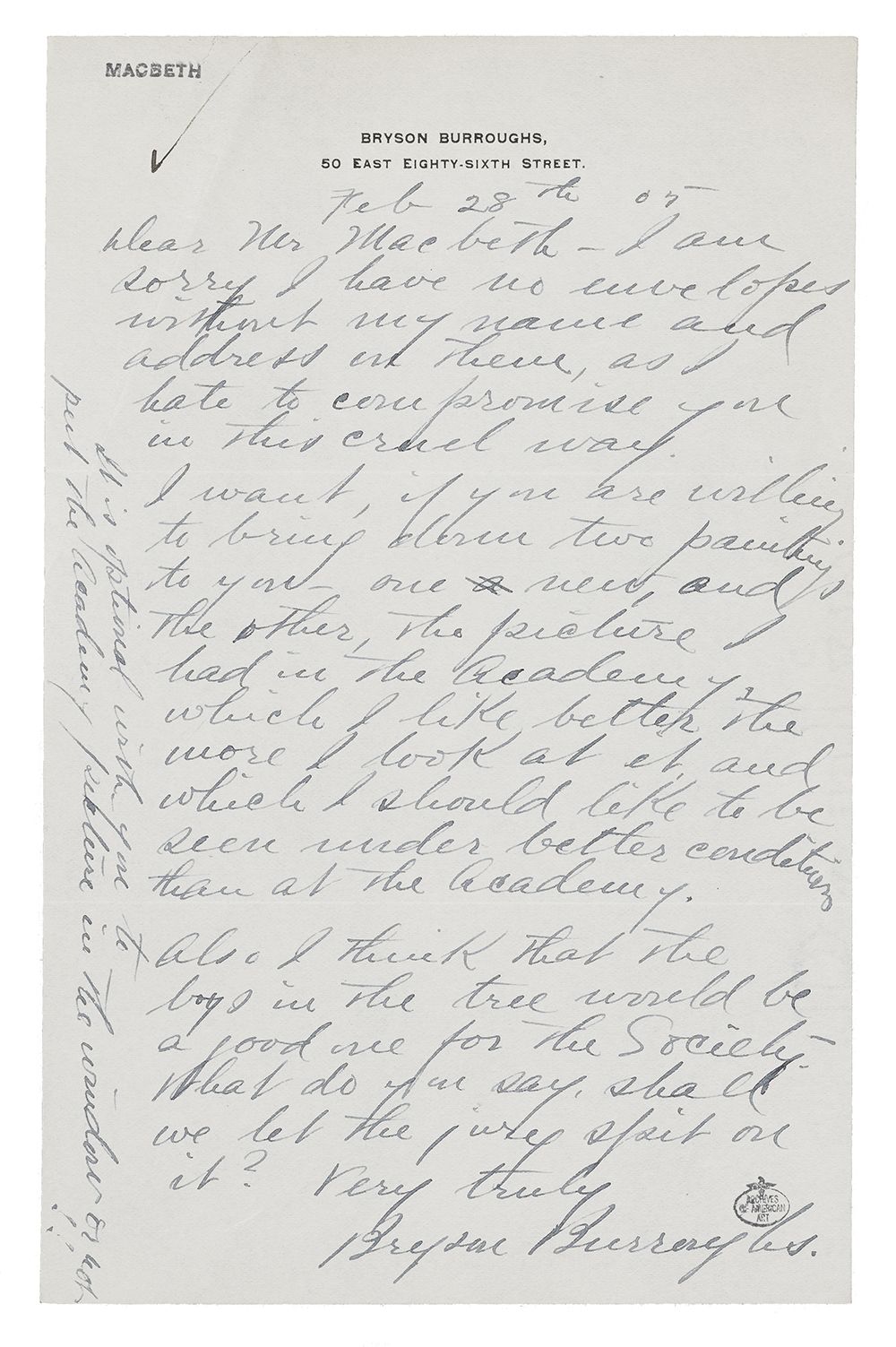

Bryson Burroughs’ daughter, sculptor Betty Burroughs Woodhouse, told me a story about being one of the models in a painting of unclothed children frolicking by a waterfall that was removed from the gallery window because it was judged obscene by Anthony Comstock, a social reformer with very Victorian ideas about morality. I was able to find newspaper clippings in the Macbeth scrapbooks—one with an image of the children that offended Comstock—and a letter from Bryson with a postscript saying that his next paintings need not be put in the window! The sales by the gallery at that moment were by other artists—William Morris Hunt, Alexander Wyant, Sargeant Kendall, and Arthur B. Davies—confirming my theory that what was sold was not necessarily what was on view.

As much as I came to respect the gallery and its operation, I soon realized that many of the claims they made about their role in American art were not completely accurate. The assertion they promoted in the 1930s that said they were the only place to buy American art in the 1890s was untrue; there were other galleries. To keep their own operation afloat in that competitive market, the Macbeth Gallery even sold popular Dutch Hague School paintings; this, however, enabled them to support American artists whose works did not sell as often or as well. We will forgive them for later tooting their own horn and forgetting these details but, for me, it served as a reminder that before you can establish something as fact you need a second source.

Do the records of this one gallery help us to better understand the world of art and commerce in the first half of the twentieth century in New York? Absolutely. Art was a business with standard practices that I now understand. And it was quite a business. The 1905–6 American Art Annual lists forty-six galleries in New York including four (Clausen, Katz, Montross, and Macbeth) who are noted as specializing in American art. (Many more likely included American art in the range of material they exhibited and sold.) Every gallery wanted to promote its artists, get newspaper reviews, and encourage sales. Based on the number of Macbeth artists who have made it into the American art canon—everyone from George Inness to Andrew Wyeth—we know that William Macbeth and his son, Robert Macbeth, and nephew Robert McIntyre were good at their jobs. The obvious comparison is with photographer and gallery director Alfred Stieglitz, who was also a master at convincing critics and collectors that his artists were outstanding.

Today, we can see through broader research that perhaps the judgment by a Macbeth or a Stieglitz was not absolute; all artists did not necessarily get a fair shake. There were good artists who exhibited elsewhere, including in other cities. For whatever reason—an art dealer who was perhaps not as good at attracting collectors or critics or an artist who did not produce enough art (a key element for developing a reputation)—certain talented artists failed to build a following.

To have this amazingly comprehensive documentation of one important gallery—now progressively available online—is an incredible resource. Everything I write involving American art of that era—about artists, museums, and collectors—draws on my Macbeth research and to be able to dip back into the Macbeth primary source material remotely is great as I work on new projects. For me, however, the danger remains of again falling down the rabbit hole: reading the unrelated letter or just one more review in the scrapbook that leads to another intriguing story. Sometimes, it’s just too much fun to stop.

This post originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog.