Aesthetics of Disobedience

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_lipplucy_66599_SIV_crop.jpg)

Part I: A Piscataway Mural Made in Solidarity with Chile

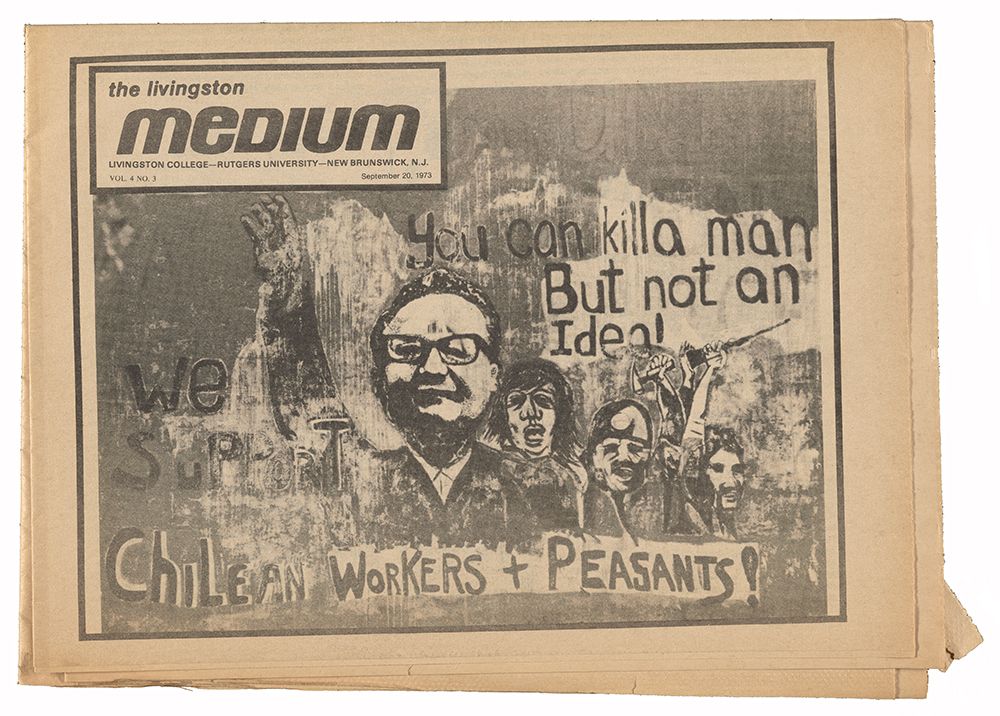

Found among the papers of art critic Lucy Lippard is the September 20, 1973 issue of The Medium, the student newspaper of Livingston College at Rutgers University. On the cover, a black and white reproduction of a mural made by students on campus shows Salvador Allende, the Chilean politician who was elected president in 1970. Wearing his signature black-framed glasses, and sharply illuminated from above, Allende, the first ever Marxist democratically elected president, is portrayed with a confident smile, his head and arm raised, addressing the people, el pueblo.* He is celebrating the victory of his left-wing coalition, Unidad Popular (Popular Unity), and thus the victory of his socialist program centered on the redistribution of land and wages, free access to health care and education, and the nationalization of natural resources owned by multinational foreign corporations. Accordingly, Allende is not alone in the image. Behind him, three men—embodying the indigenous and the peasant, the working class, and the socially committed student and intellectual—march with Allende sharing his joy. Raising their voices, hammers, and arms, they represent individual identities but also a united body that seeks the same ideal: a society with equal rights built on collectivity and solidarity.

Significantly, in this image the representation of collectivity and solidarity expands the temporal and geographical framework of the Unidad Popular’s years in Chile that ended on September 11, 1973, when a military coup, backed by the United States, destroyed the democratically elected government provoking the exile, torture, and death of thousands, among them Allende. This is evident not only in the fact that both this image and its reproduction were made in Piscataway, New Jersey after the coup, but also in the conceptual ways in which these ideas are addressed with the combination of image and text. The text on the upper right declares, “You can kill a man but not an idea!” For People’s Painters, the muralist collective who first created the image—and by extension The Medium, the socially-committed outlet reproducing it—collectivity and solidarity were ongoing and translational models for resisting the capitalist world system. Something similar occurs with the phrase “We support Chilean Workers + Peasants!” The choice to fracture the text, highlighting “Chilean Workers + Peasants!” at the bottom of the image, functions as both an identity politics banner—carried enthusiastically by the Chilean pueblo before the coup—and a post-coup motto made collectively by US cultural workers in a spirit of Pan-American solidarity. The continuity of the notion of pueblo as an international collective and solidarity network is exactly what these two Piscataway-based organizations intended and achieved. This perpetuation of ideas is even more evident in the formation of People’s Painters in the early 1970s, who took as their core influence the Brigada Ramona Parra (BRP), a Chilean muralist collective dedicated to promoting the agenda of the Unidad Popular.

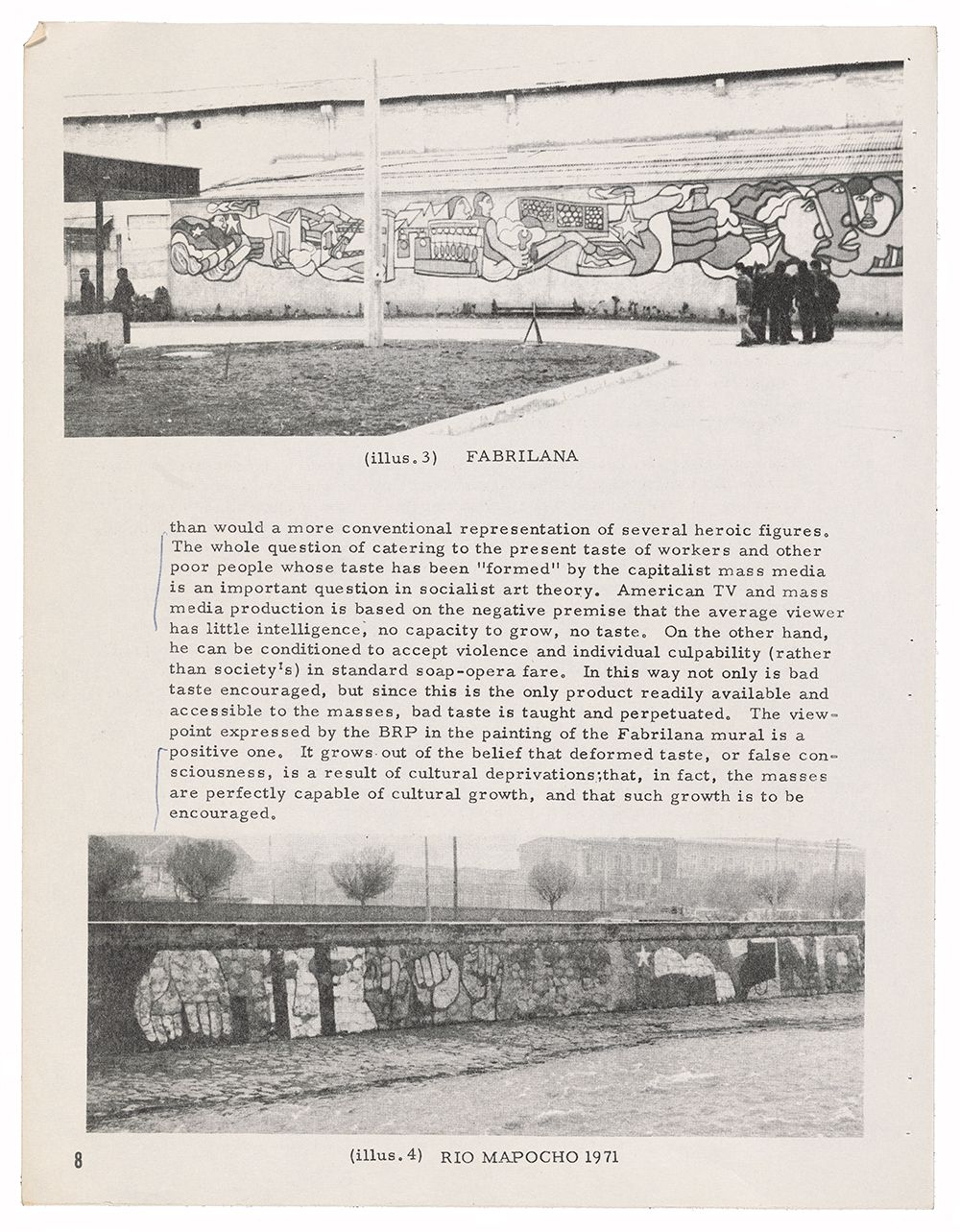

Founded in 1968 by the communist youth organization Juventudes Comunistas de Chile (JJCC) in solidarity with victims of the Vietnam War, the BRP developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s, making politically-charged, anonymous murals throughout the country, garnering the attention of socially concerned peoples internationally. In the United States, Eva Cockcroft, then an art history student at Rutgers, learned about the BRP in the spring of 1972. Influenced by the previous decade’s anti-imperialist and feminist movements, Cockcroft felt the need to experience Allende’s democratic revolution with this muralist collective first-hand. Thus, in the summer of 1972, she made a one-month trip to Chile, contacting members of the BRP, talking to them, painting with them, and photographing their work. It was upon her return to New Jersey that Cockcroft, alongside her husband James, then a professor of sociology at Rutgers, founded the People’s Painters collective. As she wrote in her essay “People’s Painters,”

On my return from Chile, I presented some [BRP] slides shows at area colleges to let people know what was happening in Chile. . . . It was in this spirit that our group was formed. After the slides show, a number of people from the audience gathered to talk more about forming a Chilean-style mural collective.

But it was not simply their style—rapid strokes, flat colors with bold black outlines, simple iconography, and the overlapping of image and text—that the New Jersey group took from the Chileans. They understood that the BRP’s formal strategy was in the service to a larger and more complex aesthetic project, making work by and for people with shared histories of repression or in solidarity with them. In so doing, People’s Painters also understood that at the heart of the BRP’s aesthetics was the making of murals that could be covered and repainted as the political agenda changed in the ongoing lucha (fight) against capitalist and neoimperialist repression.

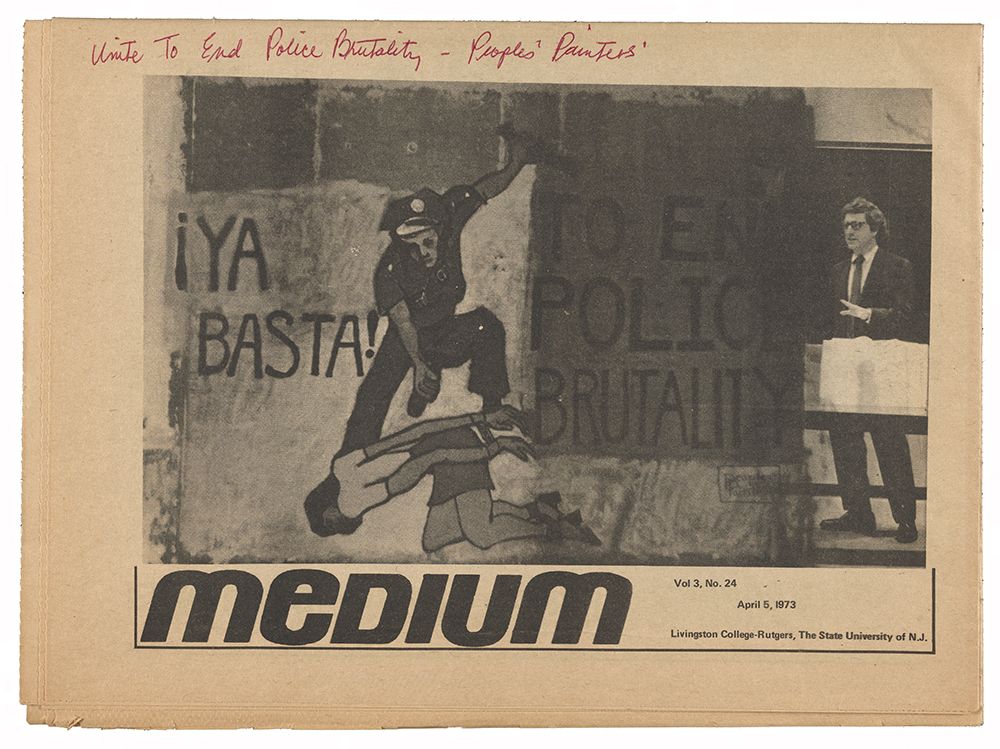

The Allende mural, for instance, was created on the same wall where People’s Painters had made another mural five months before. This earlier mural was also reproduced by The Medium for its April 5, 1973 issue, also saved in Lippard’s archive. Representing an episode of police brutality against the Latinx community that had just occurred on campus, a Puerto Rican woman, with her hands tied and knees and head on the floor, is shown at the center of the mural being beaten by a white policeman. She is painted to human scale, and at her right is the Spanish expression “¡Ya basta!” (Stop! Enough!), making visible the long and continuous history of injustice toward Puerto Ricans living in the mainland United States. On the right side of the image is the English phrase “United to end police brutality,” highlighting the urgency to collectively end police aggression toward minorities in a multilingual and multicultural nation.

Tellingly, traces of the phrase, “United to end police brutality,” are still visible on the Allende mural. On the upper right, fragments of the words “United,” “End,” and “Police” appear as ghosts of a collective and shared past that refuses erasure. This overlapping of past and present vis-à-vis police brutality against minorities in the North and state violence in South America is even more striking considering the origin of the name Brigada Ramona Parra.

A twenty-year-old Marxist from the JJCC, Ramona Parra was shot by the police in Santiago in 1946 while protesting labor rights in solidarity with striking nitrate workers. More than twenty years later, the BRP decided to honor a female, non-heroic subject whose struggles in the public space were anonymous but collective, whose death, and therefore life, went unnoticed. Fulfilling a promise made by the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, who upon Parra’s death wrote in “Los llamo” (“I Invoke Them”) from Canto General, “Ramona Parra . . . juramos en tu nombre continuar esta lucha” (“Ramona Parra . . . we swear in your name to continue this struggle”), the BRP identified itself with a luchadora del pueblo. In so doing, the collective linguistically challenged the modernist idea that public interventions—strikes, protests, art—are only organized or performed by masculine, heroic and authorial subjectivities, differentiating itself from the names used by other brigades in Chile. This linguistic strategy was also central for the People’s Painters. As Cockcroft explained in her essay “People’s Painters,” the collective used their own form of identification: the English translation of the Spanish notion of pueblo followed by the word painters. In so doing, they embodied an art made by and for the people; an art in which collectivity and solidarity were performed together to uphold the always changing demands of those left aside by modernity’s hierarchical structures.

Across the top of the April 5th issue of The Medium, the phrase “United to End Police Brutality” is written in red ink, and next to it “People’s Painters.” It is thus fair to believe that Lippard—who also told me via email that she “. . .may well have met [Cockcroft] in the 60s,” and who knew about Latin American practices merging art and politics after her well-documented trip to Argentina, chronicled by Julia Bryan-Wilson in her book Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era—was aware of the BRP and the origins of it name on the one hand, and about the relationship between People’s Painters, Allende’s Unidad Popular, and international solidarity on the other. Not surprisingly, as I will describe in the second part of this essay, Lippard participated in, and significantly helped to document and disseminate, an important art action in which a BRP mural—painted originally on the banks of the Mapocho River in Santiago and destroyed by the new military regime—was reproduced in New York in October 1973.

Part II: Reconstruction of a Chilean Mural in New York

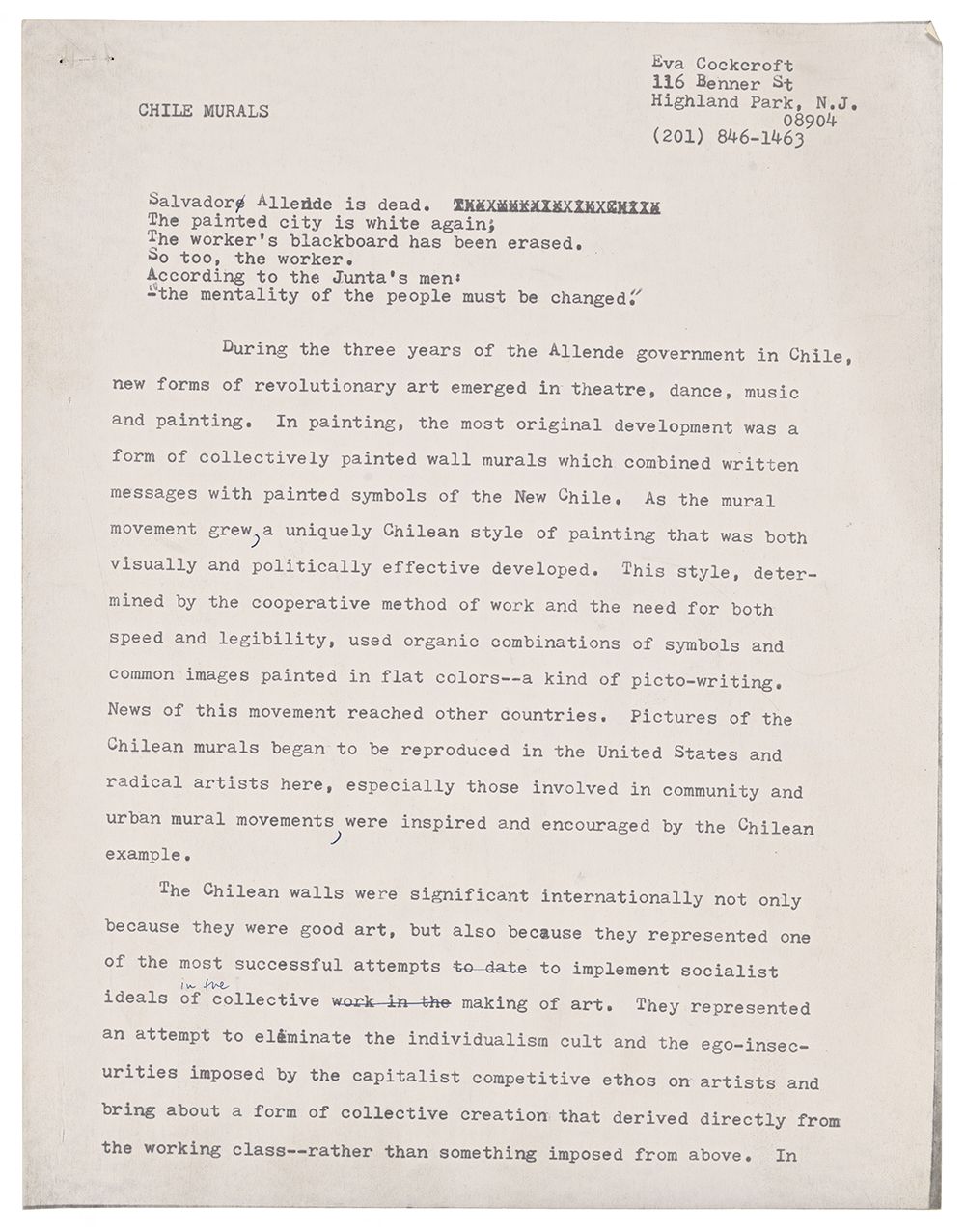

Salvador Allende is dead.

The painted city is white again;

The workers’s blackboard has been erased.

So too, the worker.

According to the Junta’s men:

“the mentality of the people must be changed.”–Epigraph to Eva Cockcroft’s unpublished essay, “Chile Murals”

On September 11, 1973, a civic-military coup backed the United States government overthrew the Chilean democracy, inaugurating a seventeen-year dictatorship that left thousands tortured, disappeared, or dead, among them the democratically elected president, Salvador Allende. In support of the Chilean victims, left-leaning artists, activists, journalists, and intellectuals in the United States—many of them former participants in the antiwar movement—protested the regime and the US’s role in that massacre through a variety of forms. In the realm of the visual arts, an important art action was the reproduction in New York of a mural originally made by the Brigada Ramona Parra in Santiago, Chile, which had been destroyed by the military in the wake of the coup.

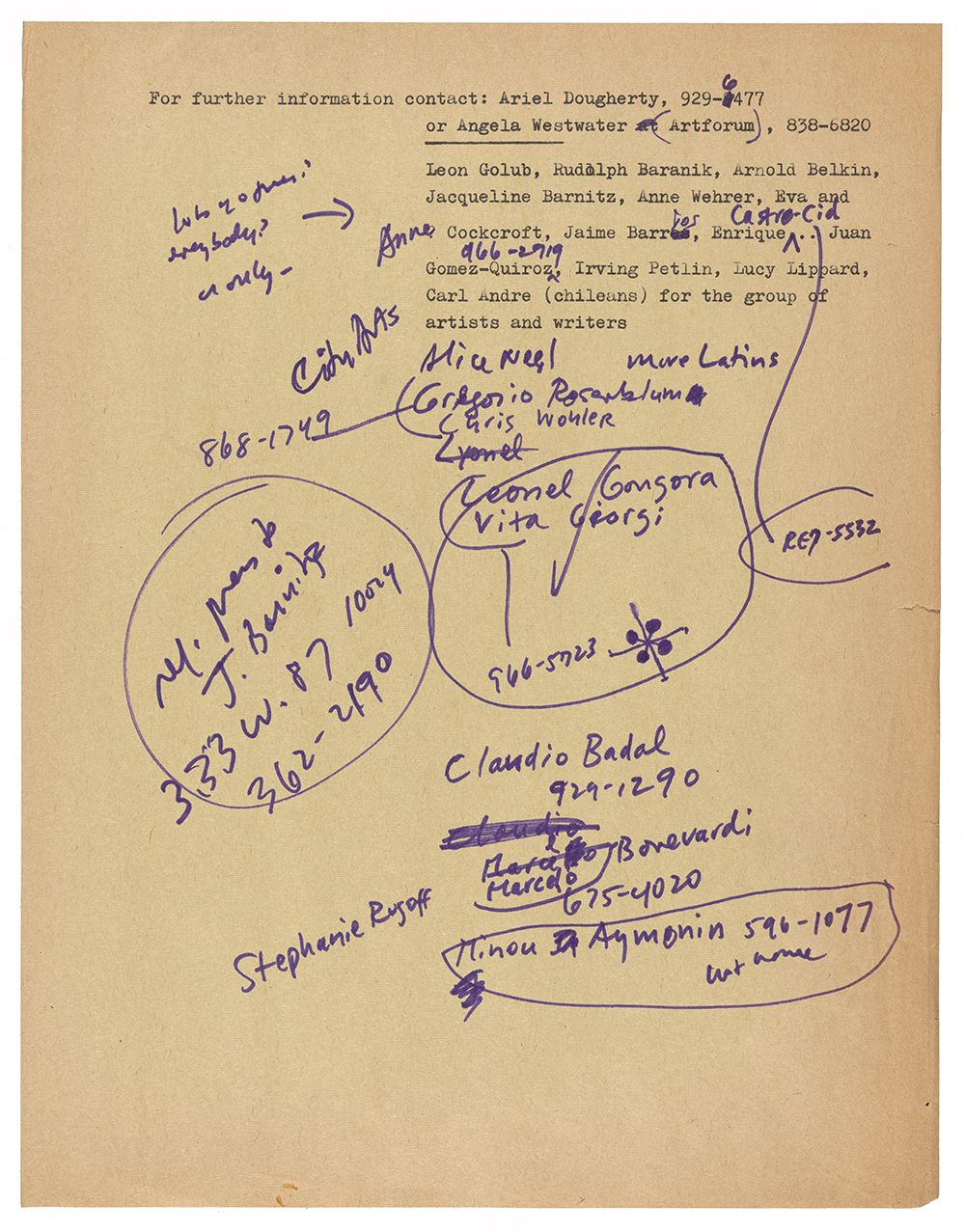

The very first in a series of art events that took place in New York, this action was organized by a group of cultural workers—including US citizens and expatriates living there at the time—in solidarity with Chile. While this collective action was undertaken anonymously, notes from art critic Lucy Lippard’s archive reveal many of the participants: Lippard herself, Angela Westwater, then an art writer for Artforum, filmmaker Ariel Maria Dougherty, and art historian Jacqueline Barnitz. Among the participating artists were Rudolf Baranik and Leon Golub, both from the United States, as well as the Argentinian Marcelo Bonevardi, the Canadian-born, Mexican citizen Arnold Belkin, the Chileans Claudio Badal, Jaime Barrios, Enrique Castro-Cid, and Juan Downey, the Colombian Leonel Góngora, and the Italian-born, Vita Giorgi.

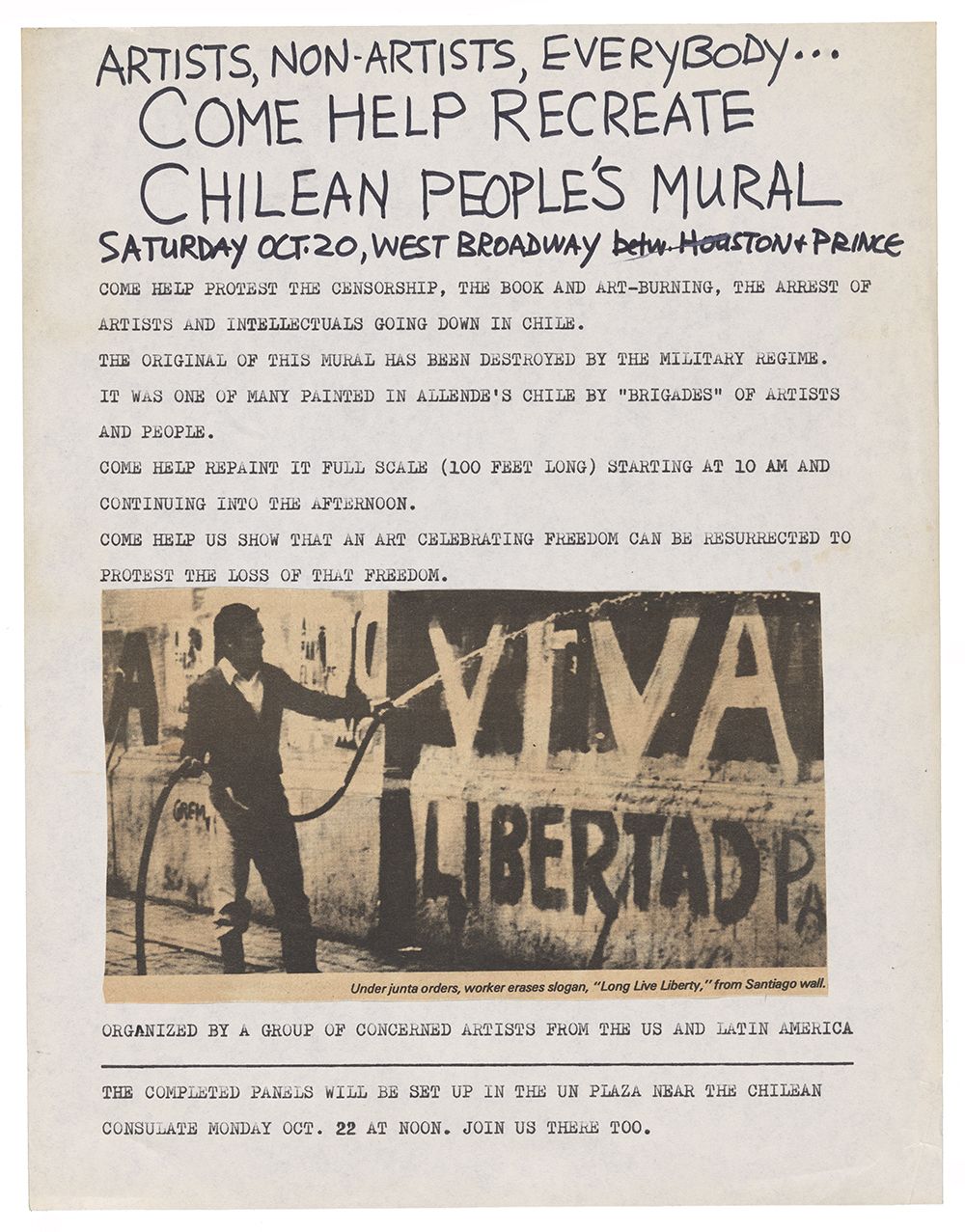

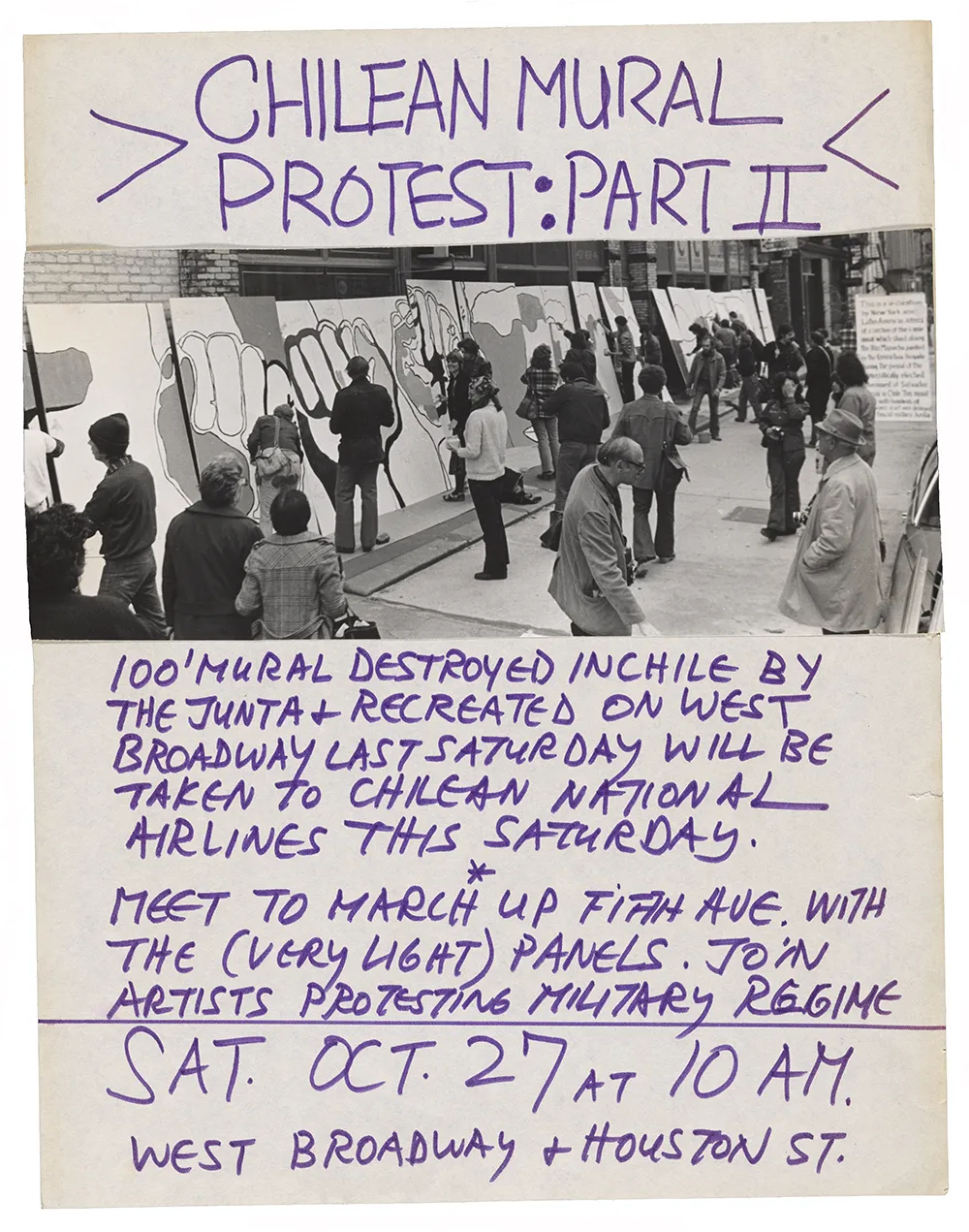

The action was divided into two parts, the first of which took place on October 20, 1973. Participants gathered in SoHo on West Broadway, between Prince and Houston Streets to reproduce collectively a one hundred-foot long segment of the BRP mural first created on the banks of the Mapocho River. Using laminate panels eight feet high and drawn from photographs of the original mural, on the Saturday of the action, from 10 a.m. on, the mural was painted anonymously by roughly fifty participants, including the cultural workers mentioned above, as well as other artists, activists, and passersby. The second part of the action occurred one week later on October 27. As directed on the poster advertising the action, participants gathered once again at ten o’clock in the morning on West Broadway, and marched uptown carrying the mural panels. Upon their arrival at Fifth Avenue, between Forty-Eighth and Forty-Ninth Streets, they set up the mural again outside the Chilean National Airlines offices, a site chosen because as one of Chile’s largest privately owned companies, they were a potent symbol of multinational power and collaboration between the US government and the newly installed dictatorship.

Lucy Lippard, in her short review of the action that appeared in the Issues & Commentary section of the January 1974 issue of Art in America, wrote, “The art-loving crowds in Soho smiled and passed on, as did the Christmas-shopping crowds of Fifth Avenue a week later when the mural was set up outside the Chilean National Airlines.” And yet, despite the lack of immediate effectiveness she noted—a matter she attributed to “the political apathy of the American art community”—as the mural was repainted, mobilized, turned into protest signs, and then reorganized as a contingent political statement, Lippard saw the action as a symbolic success. Its purpose was not simply to revive one single mural destroyed by the military regime in Chile, but also an aesthetic paradigm based on collectivity, solidarity, a theory of contingency and ongoing action. By engaging in Pan-American solidarity and invigorating the BRP’s values embodying cultural and political freedom, the action in New York underscored the prohibition of that very freedom in Chile.

However, as I write in Part I of this essay, this was not the first artistic practice that successfully replicated the BRP’s aesthetics on the East Coast. The People’s Painters mural of Salvador Allende in Piscataway, New Jersey, which despite his death represented the vitality of his ideology after the coup, is one important example. Noncoincidently, Eva Cockcroft, one of the founders of People’s Painters, appears in Lippard’s notes as one of the organizers of the New York action. Moreover, as Lippard recently recalled in an email to me, Cockcroft was the “key organizer” of the event. Consequently, many aspects of the People’s Painters collective, and more specifically their Allende mural—a post-coup, nonpermanent painting made collectively and in solidarity with the Chilean people—are present in the New York action. In fact, as planning documents in Lippard’s archive confirm, members of People’s Painters participated in October of 1973. By acknowledging Cockcroft’s firsthand knowledge of the BRP, the issue of freedom in the re-creation of the mural is better understood both historically and conceptually.

Firstly, it is important to note that for the creators of both the Piscataway and New York murals, continuity and resistance are at stake. Both were made as a critical response to the coup: the People’s Painters’ mural in New Jersey highlighted the persistence of Allende’s political principles while the New York action illuminated the endurance of the BRP’s aesthetics despite the destruction of their murals. It is well-documented that in the weeks following the coup, the military disappeared not only dissident peoples but also their ideologies. They burned books—including books of Pablo Neruda’s poetry—and painted over the BRP’s murals. Both Neruda’s promise to continue the struggle against oppression in the name of Ramona Parra—made in his 1950 poem “Los llamo” (“I Invoke Them”) from Canto General—and the fulfillment of that promise by the Brigada Ramona Parra in the late 1960s and early 1970s, were symbolically burned by the junta; as they were representative of the outlook of el pueblo, they were made to disappear. As Cockcroft wrote in the epigraph to her unpublished essay on the BRP, “According to the Junta’s men: ‘the mentality of the people must be changed.’”

Seeking to turn the formerly free public into a hegemonic, temporal, and controlled totality, the junta erased the BRP murals permanently, censoring not only their images and texts—and thus the meanings their murals conveyed—but also the freedom of its members, el pueblo, by restricting their ability to repaint on the same walls again. Accordingly, the reproduction of the BRP mural in New York was not meant to endure, to remain, but to call attention to a twofold cultural phenomenon: One, that the BRP’s murals were being censored and destroyed as were the Chilean people. Two, that the freedom of the Chilean people could be symbolically recuperated within a context of transnational solidarity through artistic actions. As the poster calling for participants for the first part of the action stated, “Come help us show that an art celebrating freedom can be resurrected to protest loss of that freedom.”

The posters from Lippard’s papers announcing both parts of the action provide key aspects regarding its relation to the BRP’s and People’s Painters’ aesthetics. For instance, the large text of the first poster reads, “Artists, non-artists, everybody…come help recreate Chilean People’s Mural.” Circulating as photocopies among and beyond the artistic community, this text highlights the ties between artist and activist, between art and civic life. Both trained artists and socially concerned people were called to participate in a work of art—an action—demanding aesthetic and political freedom, just as the BRP in Chile and the People’s Painters in New Jersey had. Other linguistic strategies followed. As the text continues (emphasis mine),

Come help protest the censorship, the book and art-burning, the arrest of artists and intellectuals going down in Chile. The original of this mural has been destroyed by the military regime. It was one of many painted in Allende’s Chile by “Brigades” of artists and people. Come help repaint it full scale (100 feet long) starting at 10 am and continuing into the afternoon.

Making clear that the mural to be reproduced was “one of many,” this is an example of a larger aesthetic practice. The title “Chilean People’s Mural” does not in fact refer to the original destroyed in Santiago, which had no official title, but rather to the action embracing the BRP’s cultural project. The same point is addressed in the image accompanying the text. Taken from a September 18, 1973 article from the New York Times, this photograph shows a worker who, following the junta’s orders, is erasing a BRP mural with the slogan “Viva la Libertad” (Long Live Liberty). While the image does not show the specific mural selected for the action, it still serves as an ideological statement: that while liberty was prohibited in Chile, it could be symbolically recuperated through aesthetic actions.

The poster announcing the second part of the action included a photograph documenting reproduction of the Mapocho River mural fragment. A horizontal image credited to the Chilean photographer Alfonso Barrios—brother of the filmmaker Jaime Barrios, one of the organizers of the event—the photograph shows people painting, observing, and walking through the scene. Among those pictured are Juan Downey, James Rosenquist and Max Kozloff. While Lippard’s archive clearly shows Downey’s role in the organization of the action, the same is not the case with Rosenquist and Kozloff. And yet, their presence in the image speaks to an important feature of the first part of the action: the site. By choosing West Broadway, a street in the heart of New York’s art world, as the location to recreate the mural fragment, the group challenged mainstream views that rejected politically engaged practices as works of art—the “political apathy” Lippard saw in the art world. Moreover, the organizers invited artists who were regulars in the gallery scene to participate, or at least to get informed about the struggles being faced by the Chilean people.

What is not noted by Lippard—or in the only other review of the event that appeared at the December, 1973 issue of Artforum written by Angela Westwater—is a more persuasive analysis of the New York action in relation to the People’s Painters’ and the BRP’s aesthetic practices. Perhaps Lippard was even conscious of this omission. Accompanying her Art in America review was an excerpt of an article about the BRP written by Eva Cockcroft, “Murals for the People of Chile,” and originally published in 1973 in Issue 4 of the San Francisco-based journal, Toward Revolutionary Art (TRA). Lippard’s gesture of putting both texts together is conceptually and geopolitically compelling, as it invites the reader—perhaps one familiar with Lippard’s “collage aesthetics”— to unearth a political message embodying past and present, democracy and dictatorship, freedom and restraint.

And yet, Cockcroft’s article was not as provocative as it could have been. Despite the collective aesthetics of the BRP, as I have written previously, there were two philosophically divergent branches within the group. One more utopian and traditional in nature, favored universal, celebratory iconography, such as flowers and doves, to represent the triumph of Salvador Allende’s left-wing coalition, Unidad Popular (Popular Unity). The other, recognizing that despite Allende’s victory Chile still had deep social and economic problems, took a more politically vigorous approach in their imagery. Writing before the coup, Cockcroft correctly highlights collectivity, the notion of el pueblo, and the unfinished quality of BRP murals in her article in TRA, but she dedicates most of the essay to commentary on the rather nontemporal and victorious iconography of the more traditional branch of the BRP. Using formal analysis based on style, Cockcroft brings established art historical sources to her narrative, such as the Mexican Renaissance and Fernand Léger’s cubism. In so doing, she builds a genealogy that highlights the artistic value of the BRP murals, but what is missed in this article is a more radical posture regarding the matter of contingency and urgency in the work of the noncelebratory branch of the brigade.

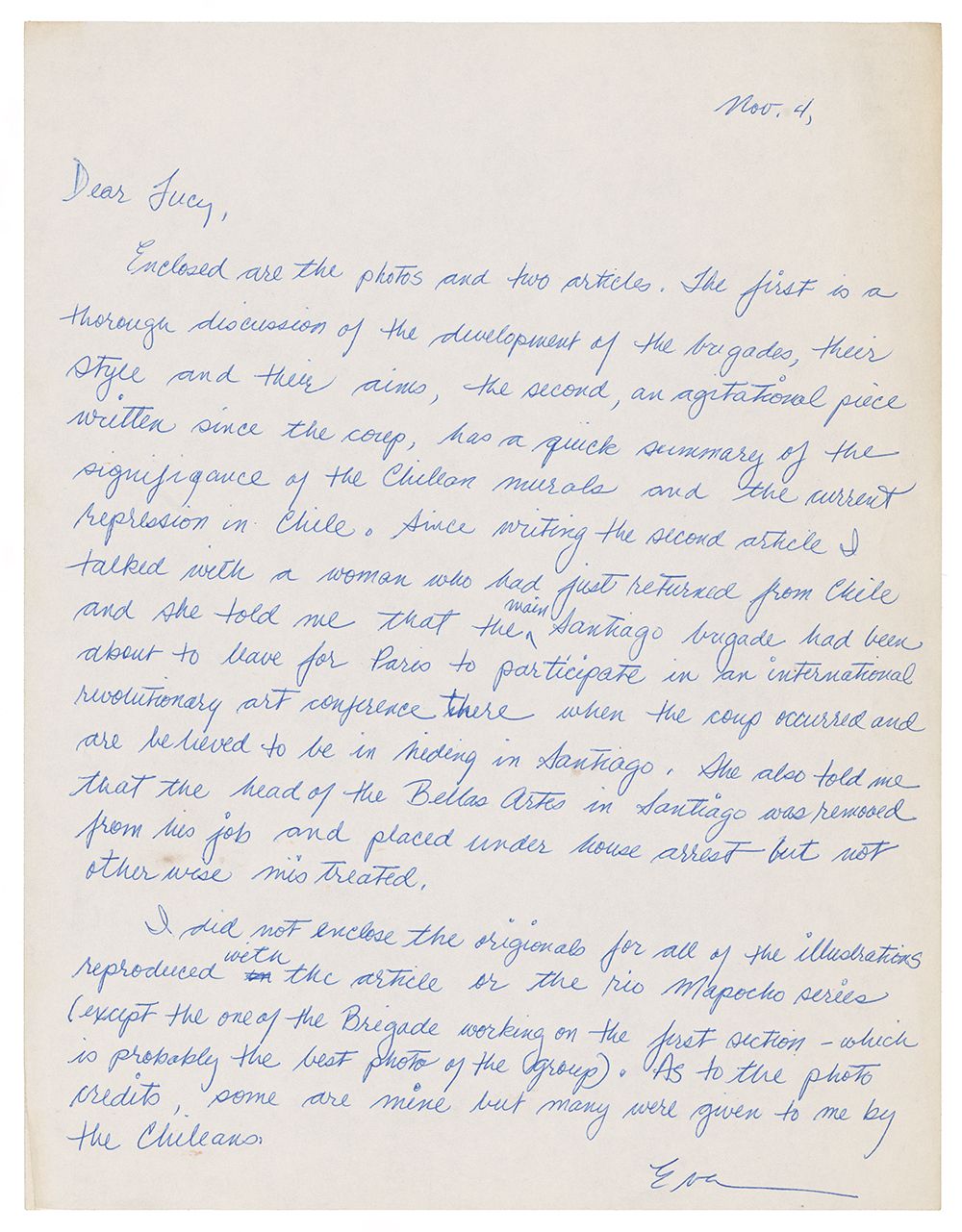

Certainly, Cockcroft herself knew about the differences inside the BRP. On November 4, 1973 she wrote to Lippard that while her article published in Toward Revolutionary Art was a “thorough discussion of the development of the brigades, their style and their aims,” a second article, which she also enclosed with the letter, was a rather “agitational piece [on] the Chilean murals and the current repression in Chile.” In this second article, which has never been published, Cockcroft writes about the New York action as a project, a planned activity to be realized, demonstrating not only her central role in the conceptualization of the action, but also her and Lippard’s awareness of the BRP’s more unruly, disruptive aesthetics. It was these aesthetics that were replicated and made visible, not only in the fact that the recreated mural was not made to last—it was meant to interrupt, to disorganize, to produce symbolic awareness—but in the very image selected.

Even though the fragment of the BRP mural chosen for the New York action—showing a face behind bars, clenched fists, a star, part of a gun, and the inscription “NO AL FASCISMO” (NO TO FASCISM)—was first made in Santiago when Salvador Allende was alive and his Unidad Popular was in power, it represented the continuity of a social struggle. Certainly, its makers were creating works in solidarity with Latin American countries whose democracies had recently been destroyed by US-backed military regimes, as was the case with the 1964 coups in Brazil and Bolivia. Moreover, the harsh iconography and text of the selected fragment was representative of the current moment in Chile. It is well-documented that in 1972, Allende’s second year in office, the political climate of the country was highly polarized due to its deep economic crisis, an outcome devised by the administration of President Richard Nixon working in concert with US and Chilean multinational corporations, including the International Telephone & Telegraph Corporation (IT&T). While this was known at the time—IT&T’s secret memos were declassified in 1972—following the coup in 1973, left-leaning international organizations and media outlets highlighted the role of private industry in the concept and planning of the Chilean dictatorship. The Medium, the student newspaper of Livingston College at Rutgers University, reported on this in their September 20, 1973 issue:

Prior to Dr. Allende’s election, the United States government had a record of financial influence in regard to Chilean policies. In the past three years, investments of U.S. owned multi-national corporations have dropped sharply from $750 to $70 million dollars. Allende’s government had succeeded in the expropriation of IT&T holdings as well as U.S. owned cooper mines (Some reports record an IT&T offer of 1 million to enlist C.I.A. aid to prevent an Allende victory in 1970).

By reproducing this section and not any other fragment or mural made in Chile by the BRP, the group in New York, and certainly People’s Painters, recognized the difference between the contingent and the celebratory branches of the BRP. In fact, the New York group’s decision to march with the mural panels to the offices of the national airlines on Fifth Avenue demonstrates their knowledge and critique regarding the role of multinational corporations in the destabilization of the Chilean economy that eventually lead to the military coup. For those against Allende—that is, for those looking to become richer within a conservative, neoliberal, and Catholic country—the coup and the civic-military dictatorship were nothing but “inevitable” actions that saved the Chilean people. As the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano once sarcastically observed, Augusto Pinochet and the junta were “torturing people so prices could be free”

This reconstruction of the BRP mural was not only the first of its kind in New York City, but also a complex aesthetic project that affected a generation of art workers living there. Moreover, the importance of this action exceeded the subject matter of Chile in the early 1970s. The photographic record—the image taken by Barrios—circulated as a referential source among artists who responded to President Ronald Reagan’s policies toward Central America in the 1980s. Specifically, as the artist Jerry Kearns told me in a recent interview, this image was shared among artists who participated Artists Call Against U.S. intervention in Central America. This nationwide political and aesthetic mobilization was organized from New York by art workers and intellectuals from across the Americas, and included gallery exhibitions, public space interventions, poetry readings, and film screenings, all taking place in 1984. Participants in the mobilization aimed “to express [their] deep concern for peace and freedom in Central America [and to] call upon the Reagan administration to halt military and economic support to the governments of El Salvador and Guatemala, to stop the military buildup in Honduras and to cease support of the Contras in Nicaragua,” as the general statement on the main poster declared. Artists Call acknowledged that “Intervention by the U.S. government inevitably reinforces colonialist and oligarchical elements hostile to the people.” Thus, participants were seeking to “speak out against these burning injustices…as long as it is necessary,” as the poster continues.

This concern about aesthetic and civic freedom, US neocolonial policies, and the production of collective, ongoing forms of mobilization, certainly recalls the political and aesthetic strategies behind the reproduction of the BRP mural in New York a decade before. Not surprisingly, alongside Daniel Flores y Ascencio, Director of INALSE, The Institute of the Arts and Letters of El Salvador in Exile, Lucy Lippard was one of Artists Call’s main organizers. Within this same line, it is also not surprising that Cecilia Vicuña, the Chilean-born, New York-based artist and poet was involved as well. Vicuña—who had produced works related to the Chilean regime in the 1970s and who in the 1980s felt deep “concern with the situation in Guatemala,” as she recalled in an email to me—was one of the organizers of, and participants in, the poetry readings for Artists Call, reading at one of these events at St. Marks Poetry Project, a “poem dedicated to the Mayan peoples of Guatemala.” As she told me in the same email, “Despues de eso, no recuerdo otra movilizacion de artistas equivalente acá en Nueva York” (“After [Artists Call], I do not remember a similar art mobilization in New York”).

In fact, Artists Call not only included artists who had been active protestors in the late 1960s and early 1970s, such as Rudolf Baranik, Leon Golub, Irving Petlin, Nancy Spero, and Vicuña, but also a new generation of artists—Doug Ashford, Alfredo Jaar, Juan Sanchez, and Kearns himself, among many others—that aimed to make visible the disastrous consequences of Reagan’s neoconservative and neoliberal policies in international affairs. In turn, Artists Call also sought to shine a light on other histories of repression in Latin America, such as the Chilean dictatorship, denouncing US intervention more broadly in both historic and geographic terms and establishing solidarity among victims of US neocolonial practices during the Cold War.

By contextualizing this never before published material from Lippard’s archive, important historical and aesthetics relations emerge around the Brigada Ramona Parra, People’s Painters, and the New York action in the early 1970s. They all embodied contingency (to paint and repaint on the same wall); memory (to paint and repaint in the name of those luchadoras y luchadores del pueblo); and translational solidarity (to paint for those sharing similar histories of neoimperialist domination). In the US, these art events—including Artists Call, also understudied in US, Latin American, and Latino art histories—were realized by art workers from different backgrounds and heritages in a spirit of Pan-American solidarity. Their significance relies not only in their existence but also in the ways in which they were conceptualized aesthetically and distributed in a coherent political dialogue with their counterparts in the Americas.

* Words like el pueblo are gendered male in the Spanish language, but also function grammatically as an all-gender plural.

A version of this essay originally appeared in two parts on the Archives of American Art Blog.