Cohorts and Collaborators: Fred Becker’s Connections through Printmaking

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_beckfred_66875-crop_SIV.jpg)

Beyond documenting the life and work of an exemplary artist, a key strength of the Fred Becker papers is the wealth of interconnections between himself and highly influential artist collaboratives and art movements, as well as cultural and political movements, they evidence. Key among these affiliations are his work produced for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and his early involvement throughout the 1940s in the New York installment of the printmaking collective Atelier 17, notably interrupted by his departure for the Office of War Information efforts in China in 1945.

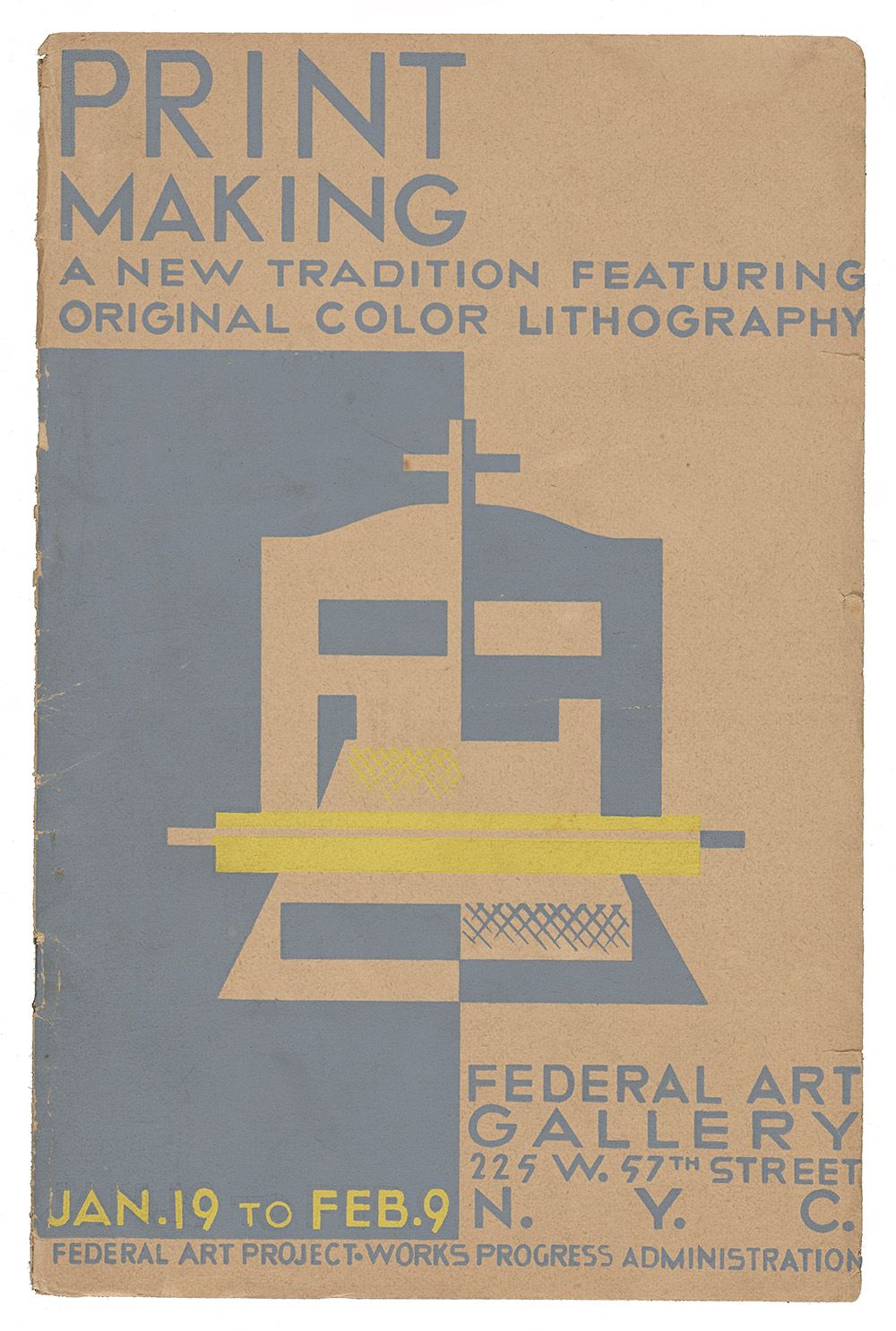

Becker attended art school in New York City and from 1935–1939 found employment with the WPA’s Graphic Arts Division of the Federal Art Project, for which he made works that largely mirrored the culture around him in lively wood engravings of city scenes and the interiors of jazz clubs in a figurative yet surrealist sensibility. During this period Becker caught the attention of Alfred Barr, the famed curator and director of the Museum of Modern Art, who included him in the highly influential 1936 exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism. This exhibition was an early moment in historicizing surrealism in a multigenerational context, which was helpful for Becker in that it legitimized his work as an emerging New York artist in the context of the largely European traditional narrative. Becker also participated in the 1937 WPA exhibition Printmaking: A New Tradition Featuring Original Color Lithography. The catalog includes an introduction by curator Carl Zigrosser and lists three wood engraving prints produced by the artist: Piano Player, Guitar Player, and Elevated Station.

After his time creating graphic works for the WPA, Becker became involved with the collective Atelier 17, which under the leadership of founder Stanley William (S. W.) Hayter was deeply entrenched in the avant-garde movements of both surrealism and abstract expressionism. Founded in Paris in 1927, then destined for New York City in 1940 in time with the German Occupation of France, Atelier 17 was a site of experimentation and collaboration credited with a number of innovations in printmaking. Artists who created work during the New York iteration of Atelier 17 include Louise Bourgeois, Werner Drewes, Joan Miró, and Willem de Kooning.

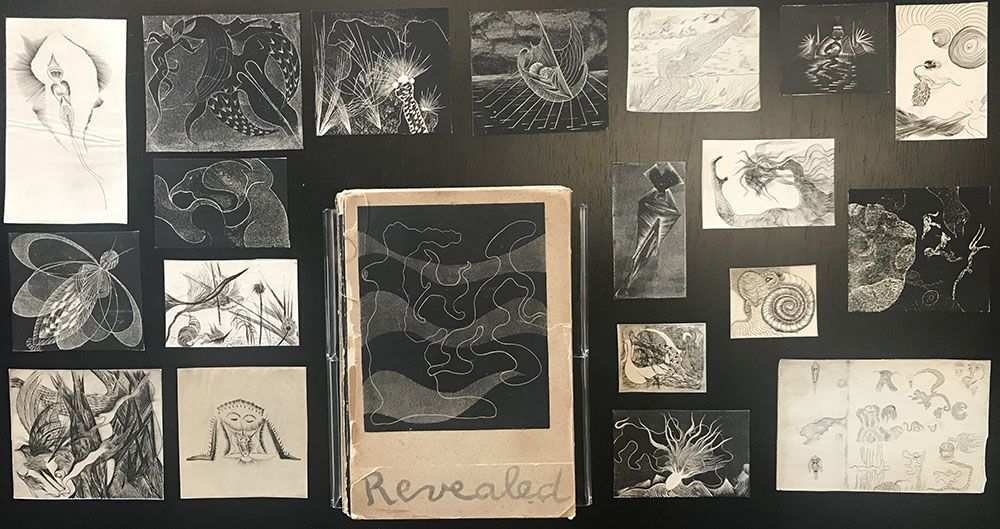

A somewhat mysterious object of interest can be found in a bound book with a pasted cover featuring etchings and hand-painted lettering titled Revealed. The text of the book is comprised of the same four pages of text from Anaïs Nin’s self-published Gemor Press 1942 letterpress edition of Winter of Artifice repeated throughout the volume. The book is accompanied by nearly forty original etchings by the artist and filmmaker Ian Hugo—a pseudonym for Nin’s husband Hugh Parker Guiler—which bear glue markings matching the pages of text. While the text of the book is an excerpt from Nin’s Winter of Artifice, both that title as well as Nin’s 1945 Gemor Press publication produced by the same methods, Under a Glass Bell, incorporate a different selection of the Ian Hugo prints found with the bound volume in Becker’s papers.

Ian Hugo is known to have been actively involved with the New York cohort of Atelier 17 and likely was working on printing and layout for his contribution to his wife’s publishing efforts. Notably the prints, which were printed in relief directly on the pages of letterpress text of both Gemor Press titles were placed irregularly on the page and would have required a considerable coordinated effort between Hugo and Nin in producing their limited edition publications. While Ian Hugo and Fred Becker were friends and active correspondents beyond their respective involvement in Atelier 17, it is unknown how the book and prints ended up in Becker’s possession. One can perhaps draw the meaning in the title “Revealed” from the statement of edition for Winter of Artifice: “For the engravings on copper in the text and cover Ian Hugo has used the technique which William Blake called ‘revealed’ because it was revealed to him by his brother in a dream.”

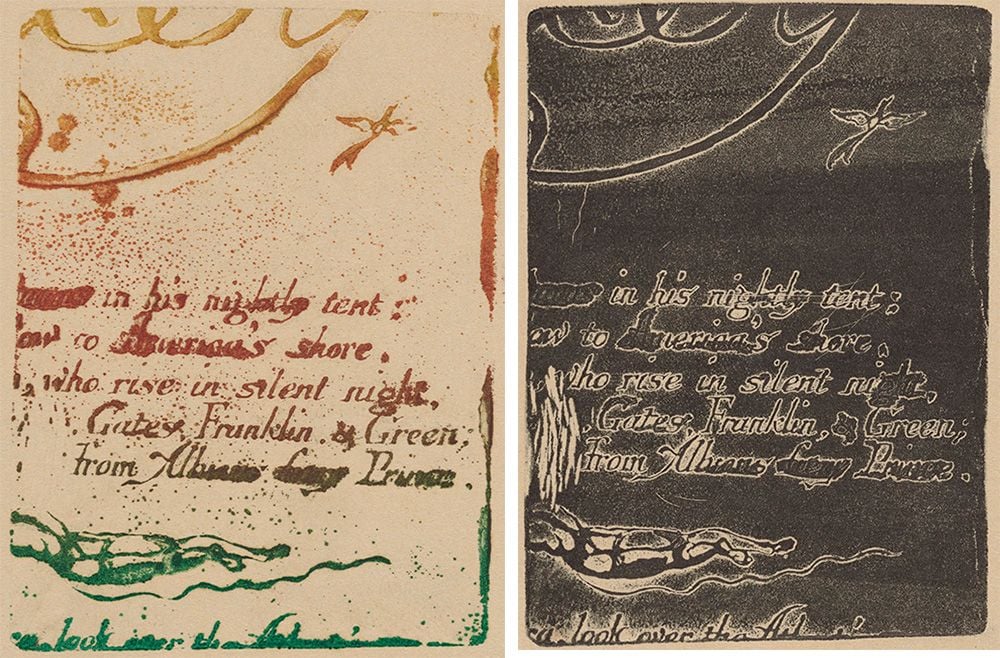

Further traces of the legacy of experimentation in printmaking can be found in Fred Becker’s papers. Like Ian Hugo, other members of Atelier 17 concerned themselves with recreating the insufficiently understood techniques of William Blake. In 1947, S. W. Hayter, in collaboration with the Scottish poet and William Blake scholar Ruthven Todd, sought to recreate the process of printing etching text in relief by working with a fragment of an original plate created by Blake. This research endeavor—with contributions by other artists active at Atelier 17 including Becker—evolved into plans to create a portfolio of poetry with accompanying artwork replicating these newly understood techniques, for which Todd would contribute poems on a number of artists including Paul Klee, Joan Miró and Hayter himself. Becker’s papers feature examples of printing made from the William Blake plate (with a fragment from the poem “America a Prophecy”), as well as Todd’s original typed poetry. While a number of prints on certain artists from the series have surfaced in auctions, the portfolio is believed to be unrealized as a whole.

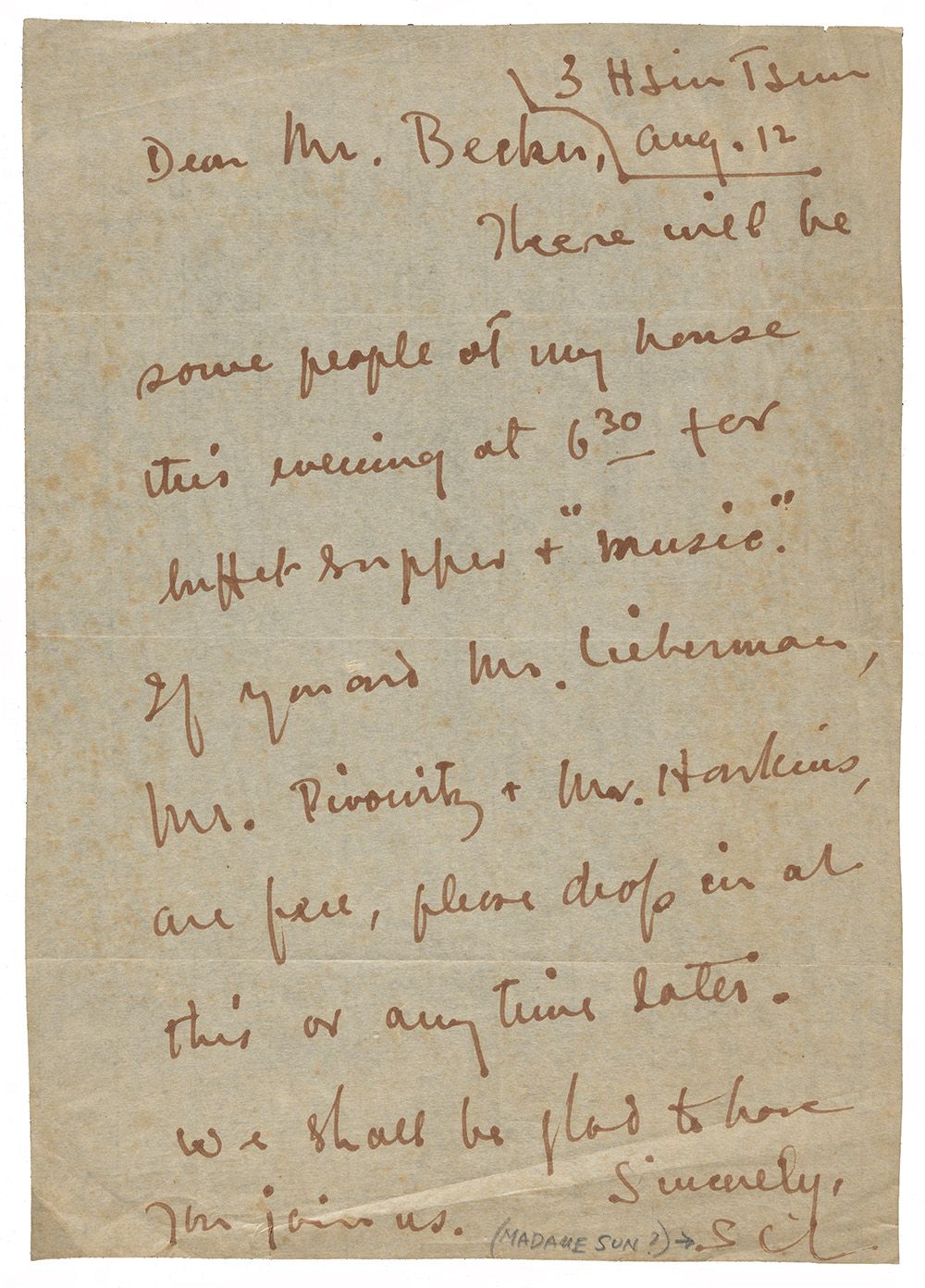

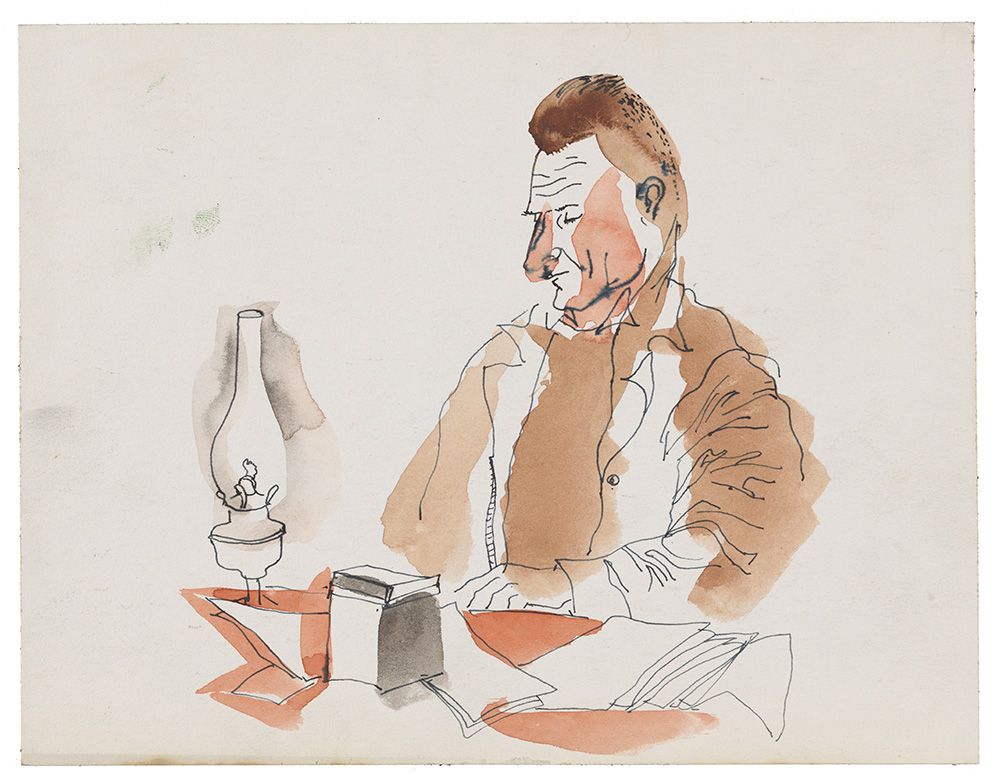

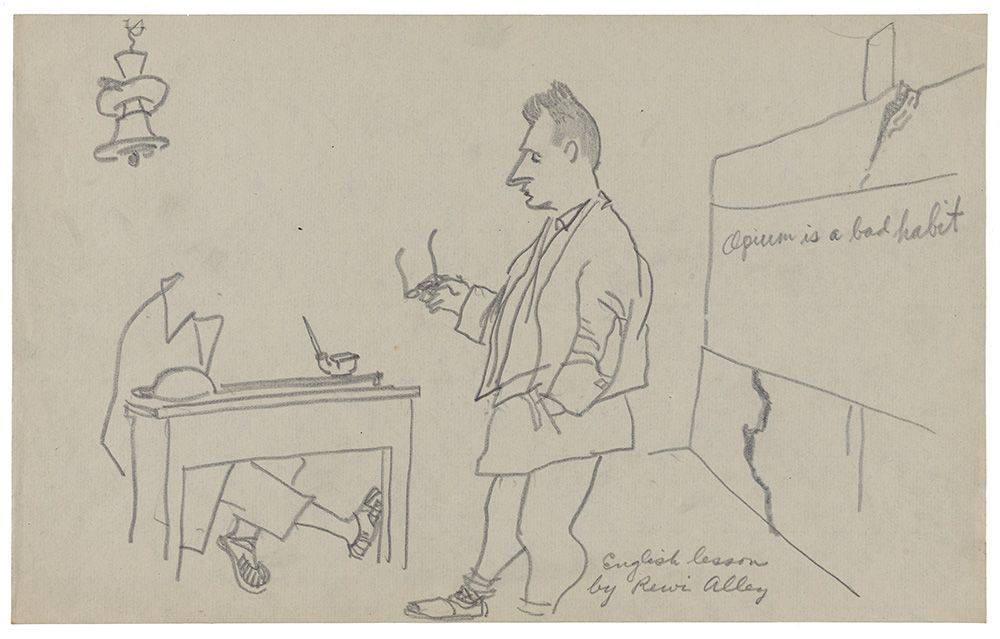

Becker’s brief service for the Office of War Information in China (1945–1946) coincided with the burgeoning Communist Cultural Revolution and there is evidence in the collection of close personal relationships with dignitaries including Soong Ching-ling—later to be named the honorary president of the People’s Republic of China, also known as Madame Sun Yat-sen—and Rewi Alley. Letters detail salon-like dinners thrown by Soong Ching-ling where Becker was among the invited guests. Rewi Alley, a New Zealander expat, was a founding member of the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives, which arose from the activities of grassroots organizers invested in creating employment opportunities during the war, eventually earning bipartisan support of the Chinese government. The two were known to be friends and Soong Ching-ling even served as Honorary Chair of the International Committee for the Promotion of Chinese Industrial Cooperatives, which is still active today. Included in Becker’s papers are a number of loose drawings and sketchbooks that serve as a kind of travel diary, including portraits of Rewi Alley, images of him involved in instruction, and various labor scenes likely captured in the cooperatives. Of note is an image of Alley’s classroom detailing a quotidian scene of an English lesson with the phrase “Opium is a bad habit” written on the chalkboard.

The Fred Becker papers, while of a modest size, are incredibly dense in rich visual and textual resources relating to his various relationship with these artistic, cultural, and political historical moments. Particularly with regard to the activities of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Program and Atelier 17’s contributions to printmaking, Becker’s papers demonstrate his integral role in these collaborations.

A version of this post originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog.