Looking in Unexpected Places: Miscellany in Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s Papers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_whitgert_1988415_SIV.jpg)

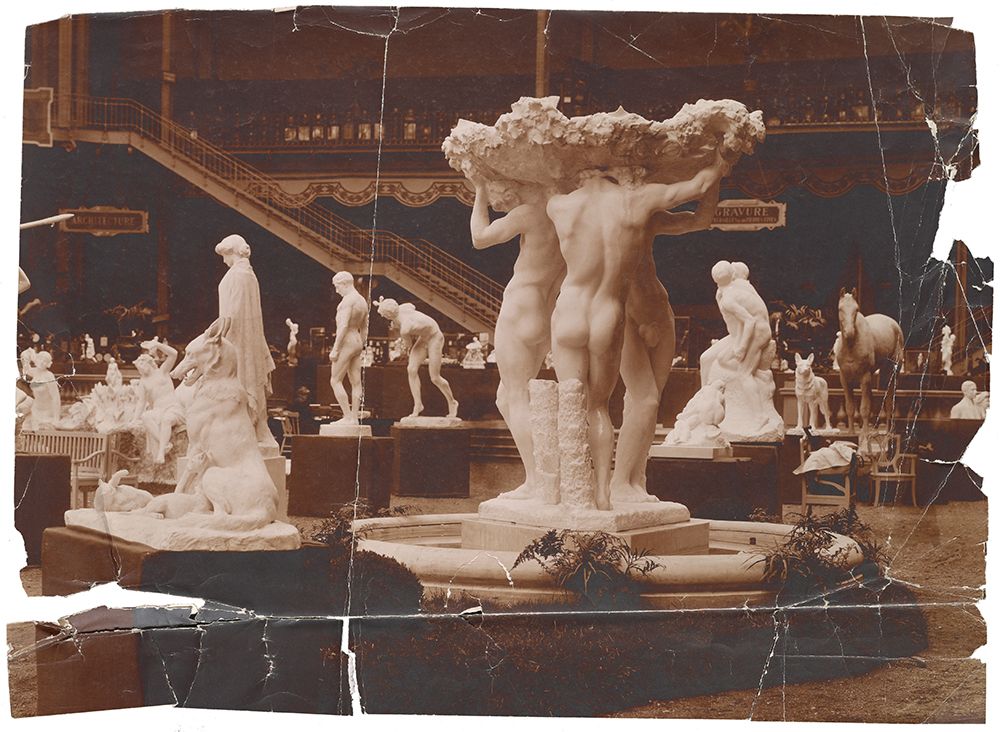

In the summer of 2018, I undertook what I thought would be a straightforward research project at the McGill University Visual Arts Collection: examining Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s papers in the Archives of American Art for any information regarding Whitney’s 1913 sculpture Fountain. This work of art is an unusual sight on our campus; a larger than life-size sculpture of three men holding up a basin, affectionately nicknamed “The Three Bares.” We knew that the artwork was a gift of the artist in 1931—Whitney was friends with Ellen Ballon, a McGill Conservatory of Music graduate, in New York and it was through Ballon that the donation was made to the university—but little else. We thought that there must be more information on how the sculpture was created within Whitney’s files.

My primary assignment was to merge and reconcile the information found in both the McGill University Archives, which holds copies of the letters received about the sculpture, and the related material in the Archives. Previous research had revealed that the sculpture was originally created for the New Arlington Hotel in Washington, DC, but the hotel was never built. Early photographs documented that it was exhibited in the 1913 Paris Salon and shown at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. We also knew that when it came to McGill, it gained a new name: Friendship Fountain, or Goodwill Fountain, so named on the behalf of the committee of influential Americans that lent their names and reputation to the donation.

The folder titled “Arlington Fountain/Friendship Fountain” in Whitney’s sculpture files contained the correspondence from McGill I sought for my project. However, as I soon discovered, folders for other works by Whitney that were commissioned around the same time—including the Titanic Memorial and the Aztec Fountain—contained numerous preparatory sketches for the works. Fountain had no such draft work. It seemed to have appeared out of thin air.

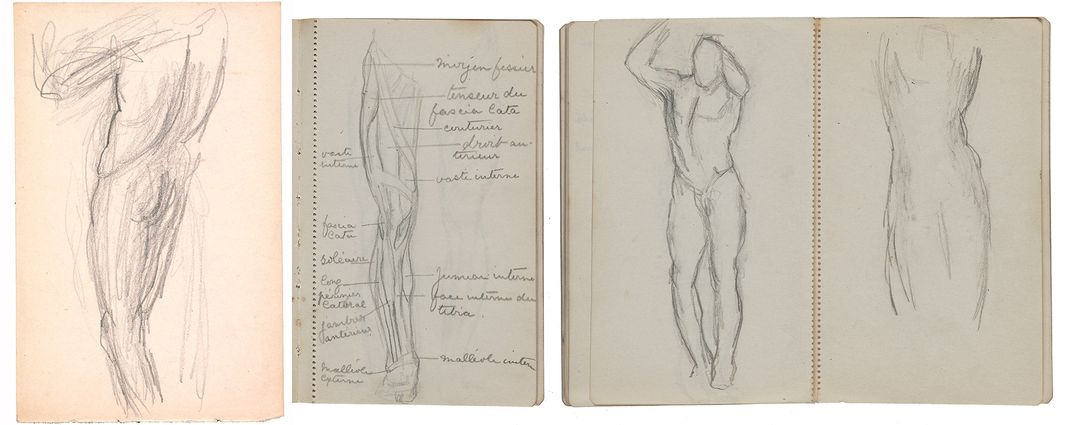

Early on in my research, I found sketches of anatomical figures in a folder entitled “Figure Studies, Other Sketches, and Notes, undated.” I had a hunch that these drawings were linked to the design of our fountain, as many of the figures in the sketches were in the same poses as the figures in the fountain. However, I had no concrete evidence. Were they really related to our sculpture? Why were they not in the Fountain files?

I kept the idea of tangential information in mind throughout the summer. As I worked, I learned that during the period between mid-1911, when Whitney would have received the original commission, and early 1913, when the fountain was being modeled in Paris, she spent time studying human anatomy. That same year, while modeling the male figures, Whitney began a long distance yet passionate affair with New York stockbroker William Stackpole.

Some of the letters exchanged between Stackpole and Whitney—many of which were not addressed as such, but were identified by her biographer B.H. Friedman and painstakingly transcribed by Whitney herself—were a goldmine of information about the artistic process. In them, Whitney detailed the process of sculpting Fountain:

There is a chance that I can finish the old fountain for the Salon and perhaps that is why I am so happy. I flew at it and had a fine day’s work, six good hours (it was dark at four) …. It makes me feel marvelously to be at the real work again!!

Just as Fountain went by many names throughout the years, in her letters, Whitney referred to the work alternatively as Fountain, Caryatid, and Caryatid Fountain. To say the least, the constant name changing was not very helpful for my research purposes.

I learned that while Whitney was working on Fountain in Paris, she kept close contact with artist Andrew O’Connor, who served as her friend and mentor and helped her study anatomy. She met with Auguste Rodin in Paris in 1911, where he critiqued an early model of the forward-facing figure, known as Caryatid. I believe Whitney’s preoccupation with anatomical drawing, as I had observed in her notebooks, was at the forefront of her mind during the period in which she was working on Fountain. In my mind, the anatomical sketches were definitely related.

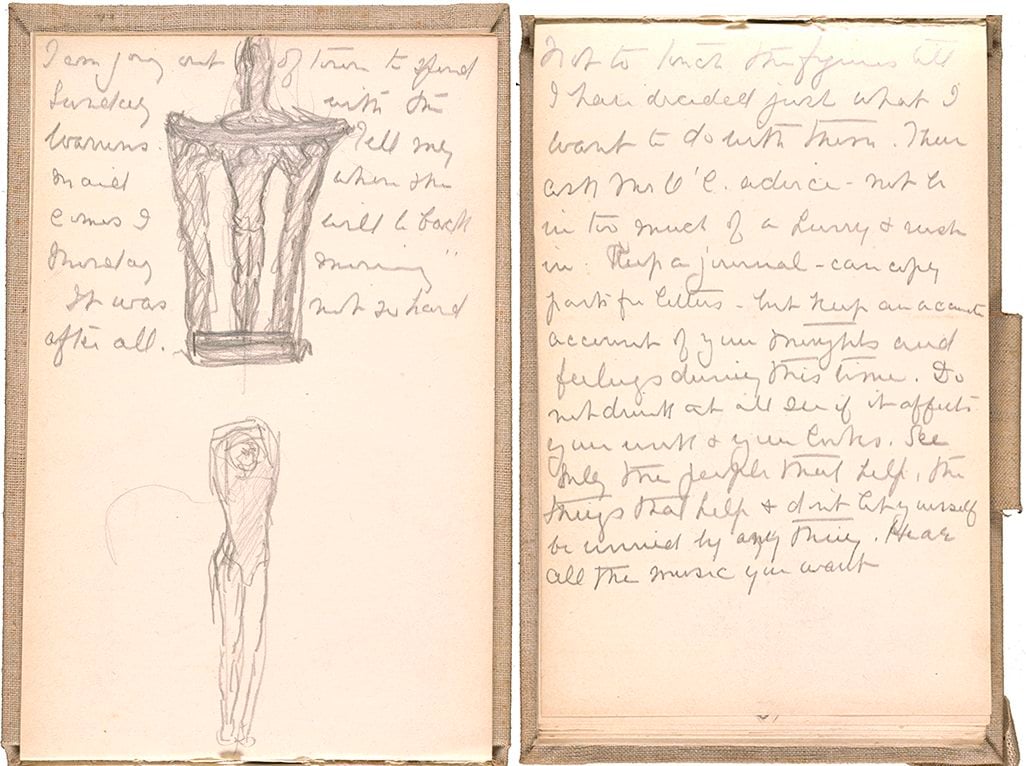

Throughout her life, Whitney kept journals and diaries filled with creative writing samples and ideas for novels. I surmised that, if I found potential evidence of rough sketches for the fountain in an undated anatomy sketchbook, I might find more in her journals. My searching led me to a folder labeled “Miscellaneous Writings and Sketches, undated,” located within a subseries of her archive dedicated to her writings. Earlier in my research, I avoided the folders labeled “miscellaneous” in favor of those that were dated and named. However, as I quickly learned, an undated document is not a meaningless document but may instead be a source for potential breakthroughs. My newfound interest in the miscellaneous folders paid off because there I discovered early sketches for the entire fountain, alongside more personal notes about the sculpting process. A note in her undated journals reflects the emotionally tumultuous time in her life:

Not to touch the figures till I have decided just what I want to do with them. Then ask Mr O’C advice - not too much of a hurry + rush in. Keep a journal - can copy parts for letters - but keep an accurate account of your thoughts and feelings during this time. Do not withdraw at all see if it affects your work + your looks. See only the people that help, the things that help + don’t let yourself be worried by anything. Hear all the music you want.

The more I searched and uncovered, the more I realized that Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s sculpture at McGill seems to have been a work that was very close to her heart. Its later name Friendship Fountain, which celebrates the friendship of Canada and the United States, did not have anything to do with its early life as a work written about in letters to a lover. No wonder the first file I looked at contained only the McGill-related correspondence—the fountain had an entire history unrelated to its donation. It was by searching through records of the other contemporaneous material that I was able to put together a more complete story. As such, I am eternally grateful that the careful cataloging of the material by Archives staff helped me to make temporal connections that would have been impossible otherwise.

In Whitney’s papers is a photograph taken in her Paris studio, where Fountain was sculpted. In it, a massive model for the Titanic Memorial dominates the frame, while two sculptors stand in the back with a modestly-sized plaster model of Fountain. To me, this photograph serves as a visual testament to the virtue of keeping an open mind while researching. I spent hours poring over the Fountain folder when what was most important to my research was not immediately obvious. Sometimes, the most salient evidence can be found in the most unexpected places.

This essay originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog.