Val Laigo and the Mosaic of Filipino America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_laigval_68417-crop_SIV.jpg)

What is now Dr. José Rizal Park, an outdoor space for the local Beacon Hill community in Seattle, Washington, was once a condemned land. Inaccessible to the public until it was acquired in 1971 by the City of Seattle Parks Department, the land would not be dedicated until 1979. Taking the name of Filipino nationalist Dr. José Rizal, an ophthalmologist-turned-anticolonial writer who was executed by the Spanish colonial government for sedition, the park would take on a political life of its own following years of suppression. By 1981, with the completion of Filipino artist Val Laigo’s outdoor mosaic East is West, the park had acquired an artistic addition to its original attractions. As if it were watching downtown Seattle from above, Laigo’s mosaic serves as community art while functioning as a kind of historical counterpoint for the city. A reminder of the communities that are crucial to the history of Washington state, East is West calls attention to Filipino Americans as well as the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest, communities that share a deeply colonial history with the United States.

In his 1989 oral history interview for the Archives of American Art’s Northwestern Asian American Project, Laigo spoke to the liminal status of the Filipino in the United States. “Having been born in the Philippine Islands, a territory of the US, I was not regarded as an alien like the Chinese or Japanese, nor as an American,” Laigo explained. After all, to be a child of an imperial territory is to be haphazardly incorporated into the nation’s citizenry. Born on January 23, 1930 in Naguilian, La Union, Philippines, Val Laigo inherited the precarious identity of his birthplace. Moving to the United States as a child, Laigo went on to neutralize his name in the interest of assimilation, legally pivoting from Valeriano to Val. As her grew older though, he came to regret purging the name given to him by his family. “I now, in retrospect, have misgivings,” he remarked. “I feel myself to be a ‘Valeriano’ at heart.”

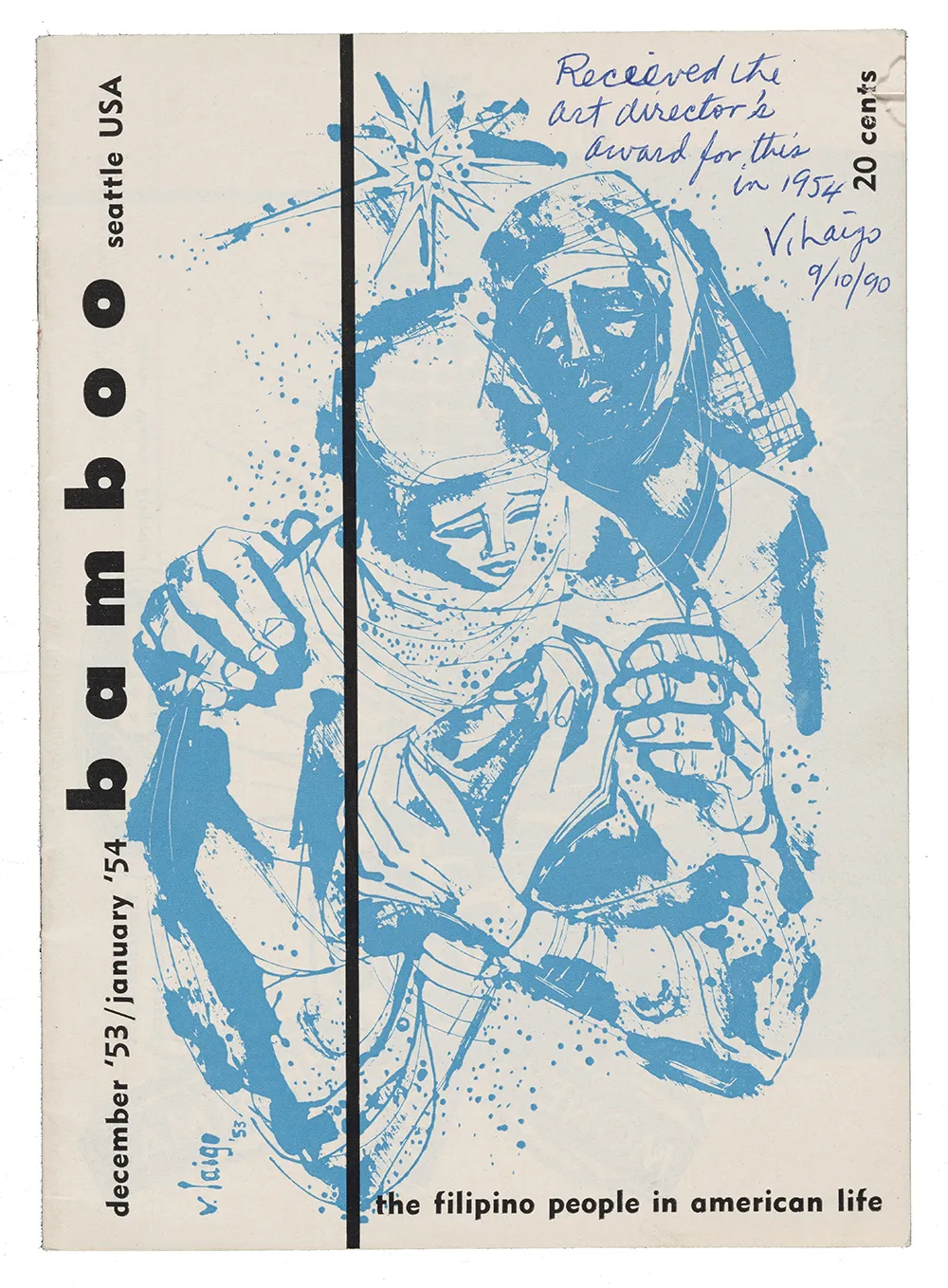

Settling in Washington state in the 1930s, Laigo ultimately found a community in Seattle that sustained his identity as a Filipino American and a burgeoning artist. In 1950, Laigo acted as publisher of Orientale, a small local magazine dedicated to issues affecting Asian American communities. Starting his professional art career in 1952, he first worked as an artist in the editorial department at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Also active in community service, he volunteered with the Seattle Youth Service Center for several years before he graduated from Seattle University in 1954. Laigo later received an art director’s award for his work at Bamboo, a magazine focused on the “Filipino people in American life,” a copy of which exists in his papers.

Serving the greater Seattle community as an artist, teacher, and advocate, Laigo often committed his talents to local projects. Throughout the 1960s, he painted several community murals in medical centers and reading rooms, including a sixty-five-foot-long work depicting Jesuit iconography for Lemieux Library at SeattleU. In 1965, as a new faculty member in the Department of Fine Arts at Seattle University, Laigo began designing courses dedicated to the art practices of non-Western cultures, revolutionizing the state of Washington’s art history offerings. Laigo’s work as a course designer led to the incorporation of non-Western art major requirements at SeattleU and University of Washington, where he also worked as an art professor.

In 1981, four years before his chronic health troubles would put him on a permanent medical leave, Laigo completed what is arguably his most popular work, the East is West mosaic in José Rizal Park. Heavily supported by community funding, East is West was, in a way, the culmination of Laigo’s legacy as an artist and advocate for Filipino Americans. Diagnosed with the congenital heart defect, Eisenmenger’s Complex, as a child, Laigo lived with the urgency of a man who understood how fickle life can be. Dedicating himself to service, Laigo worked alongside organizations such as the Filipino Catholic Youth, the Filipino Community of Seattle, Filipino Youth Activities of Seattle, the Art Mobile Project for Educational Service District No. 11, the Asian American Education Association, and the Filipino American National Historical Society. With East is West, all his years of community organizing were channeled in the crafting of an unprecedented work of public art.

The Seattle Office of Arts & Culture described Laigo’s sculpture and its symbolism alongside a series of stories on Beacon Hill’s public art. Of East is West, the post reads,

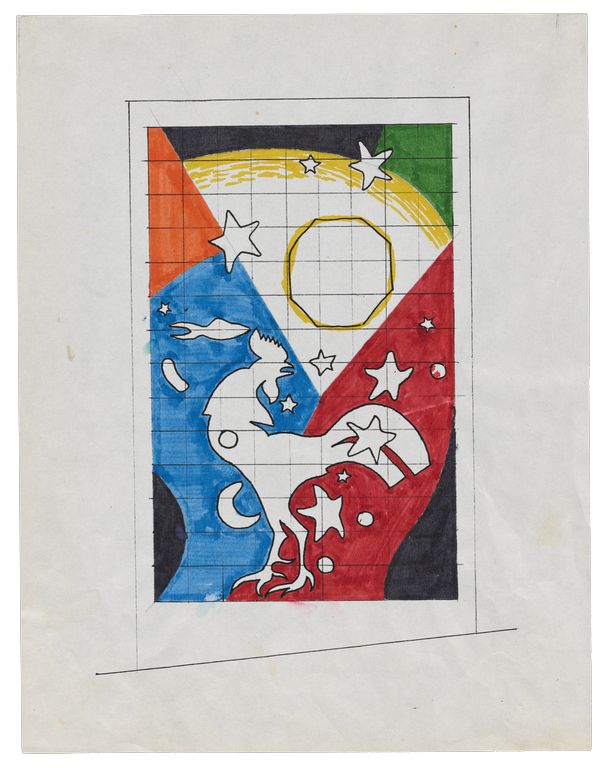

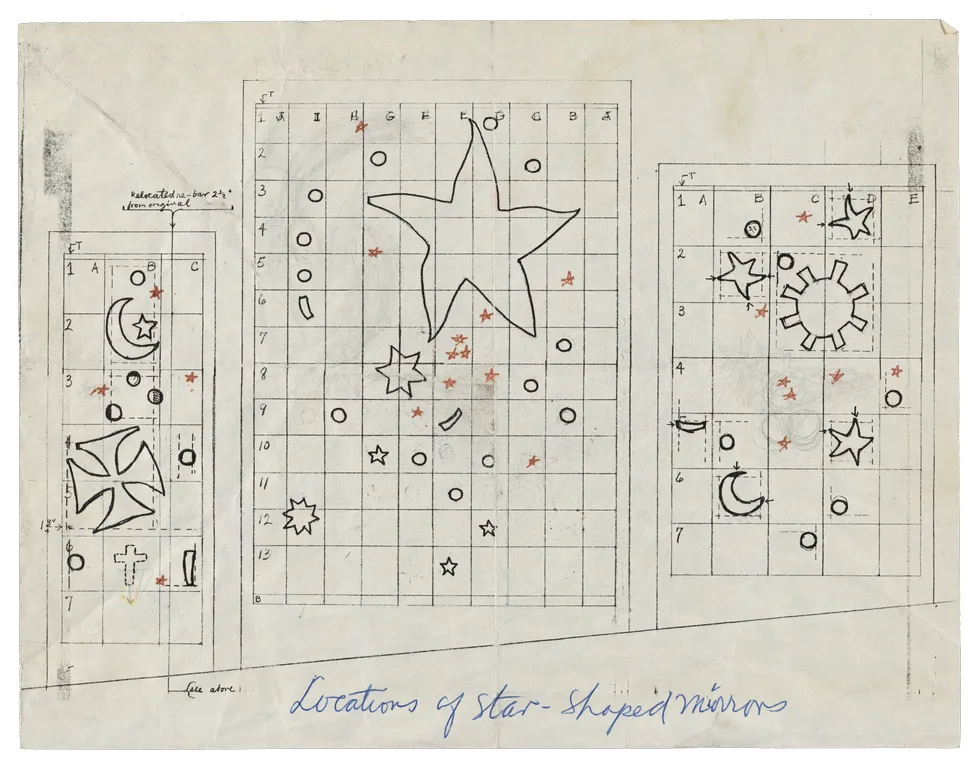

The west-facing side of the mural is of an abstract design. The east-facing side of the mural refers to mythological and cultural symbology and is comprised of three sections. In the first section, the colors of the Spanish flag (red and yellow) are favored, along with European/Christian imagery: the ichthys, the head of a bull, the cross. The second section, in red, white, and blue includes Jewish, American and Chinese stars; milkfish, a Philippine food source; and rooster imagery, which is symbolic of Malayan cultures. The third section uses the colors of the flag of the Philippines (red, yellow, blue, and white), and depicts various mythological creatures, including the salmon as a symbol of Northwest Natives.

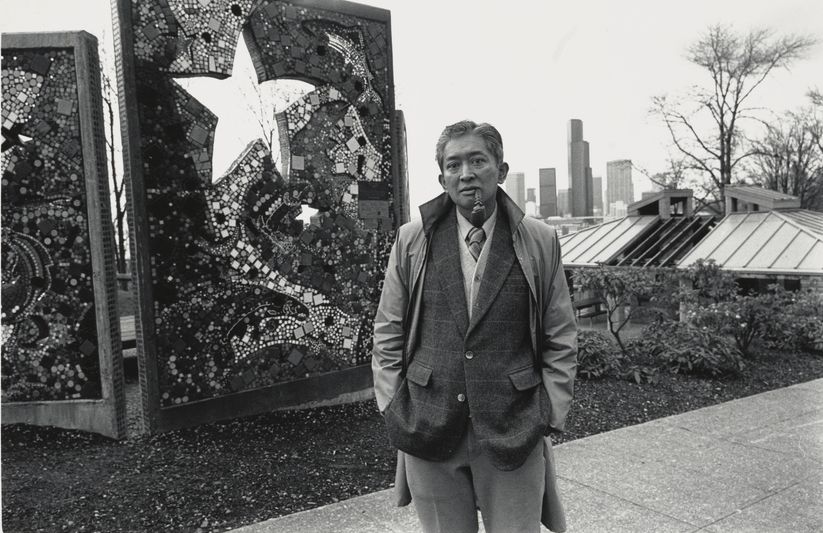

In several photographs from his collection, Val Laigo poses alongside the mosaic from various angles. With a popped collar and a pipe resting in his mouth, Laigo appears in one photo as an aging artist standing before a work that would outlive him. Enjoying a rich career and an unexpectedly long life, Laigo committed himself to art until his death in 1992. A testament to the significance and longevity of his public art, Seattle-born Filipino-American poet Robert Francis Flor honored Laigo’s work for a new generation. In 2010, nearly two decades after Val Laigo’s passing, in his poetry book Alaskero Memories Flor describes East is West as a “homage to Filipinos who crossed the ocean of dreams.” Located in a space dedicated to movement, imagination, and community, the mosaic’s placement in José Rizal Park continues to serve as a symbol for Seattle’s Filipino immigrants and their descendants, who have been shaped by colonial and imperial histories but also histories of resistance.

As Val Laigo eloquently put it in his interview, war is a “vacant thing.” Empty and devoid of integrity, the Spanish-American War that ceded colonial authority of the Philippines to the US mutated into a war for Filipino independence, also known as the Philippene-American War of 1899–1902, or the Philippine Insurgency. In the end, the United States maintained control of the archipelago, vowing incremental freedom until independence was won in 1946. Born into this historic conflict in 1930, the personal, political, and artistic life of Val Laigo demonstrates that the history of the Philippines is extricable from the lived experiences of Filipinos in the Pacific Northwest. According to the 2010 Census, roughly 3.4 million Filipino Americans live in this country, a fact that ought to encourage a more active national engagement with this particular chapter in the United States’ imperial history.

In The Decolonized Eye: Filipino American Art and Performance art scholar Sarita Echavez See asserts that “the artist successfully frames the failure of the imperial frame.” Val Laigo’s East is West is a dynamic example of this kind of radical reframing. Laigo’s work locates the complex identity and influences of a people who the US government had determined to be “foreign in a domestic sense,” and collapsed the distance forged by imperialism. As an homage to the legacy of Dr. José Rizal, an activist whose primary weapons against injustice were words, it is apt that East is West would take up the charge of contending with the painful and powerful truths of Filipino American history. This time, using the language of art.

This post originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog.