One Spot of Normalcy: Chiura Obata’s Art Schools

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_obatchiu_68425_SIV-a.jpg)

We feel that art is one of the most constructive forms of education. Sincere creative endeavoring, especially in these stressing times I strongly believe will aid in developing a sense of calmness and appreciation which is so desirable and following it comes sound judgment and a spirit of cooperation.

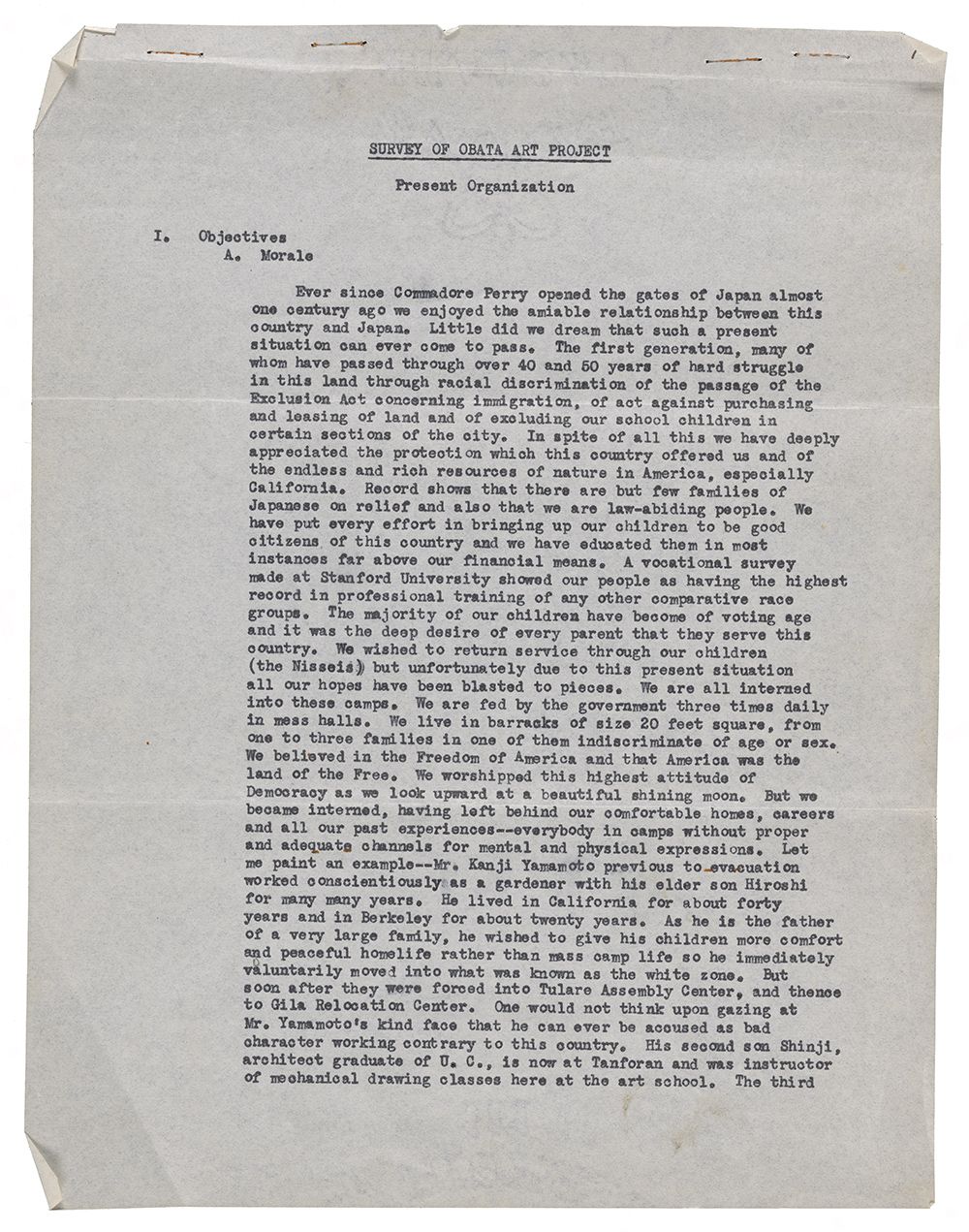

–Survey of the Obata Art Project, circa 1942

These are the words of Chiura Obata, who founded art schools at two Japanese American incarceration camps during World War II.* Most people are aware of the existence of the camps, but not as many people know that there were art schools (as well as high schools, adult education courses, and other programs) established and often run by the Japanese Americans imprisoned inside the camps. This is a short introduction to the Tanforan and Topaz Art Schools founded by Obata, based on research from the artist’s papers that are now part of the collections of the Archives of American Art.

Tanforan

In late April of 1942, Chiura Obata arrived at Tanforan Assembly Center with his wife Haruko and two of his children, Kimio and Lillian Yuri. After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7 of the previous year, the United States officially entered World War II. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the forced removal and incarceration of roughly 112,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Obata and his family were part of the approximately 7,800 people imprisoned at Tanforan, a former horse racetrack in San Bruno, California, that was used as a Japanese American incarceration camp. Individuals and families of two were forced to stay in 20' x 9' horse stalls that smelled of manure and slept on sacks filled with hay, while larger groups of people (sometimes several families) were placed in 20' x 20' barracks.

Legislation enforcing provisions of Executive Order 9066 was passed in late March, followed by Exclusion Orders that gave Japanese American families only a few days’ notice to pack some belongings, vacate their homes, and report to various “assembly centers” before being sent to incarceration camps. Most of these sites were neither prepared nor equipped to house so many people for any length of time. Artist Kay Sekimachi, who was at Tanforan with her family when she was fourteen-years-old, recalled the anguish from that period in a 2001 oral history interview, “But I must say, the first few days, I thought, when we had to stand in line at the mess hall for meals, and I really thought, gosh, are we going to survive, because nothing was organized.”

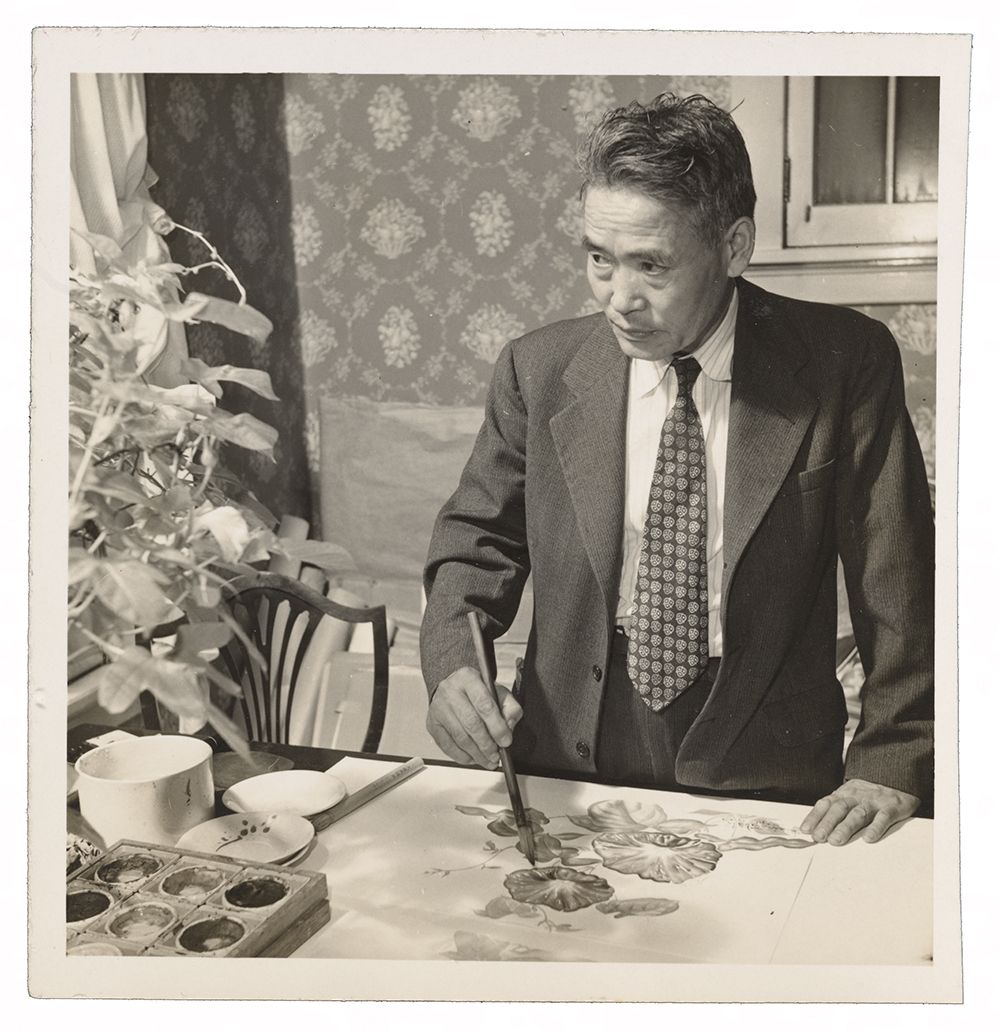

Obata was keenly aware of the children’s plight, notably the trauma caused by their displacement and incarceration. His primary motive for establishing an art school at Tanforan was to create a stable environment and hopefully give them a sense of purpose amidst the chaos. Obata, around fifty-seven years old at the time, was suited to this colossal undertaking since he was a beloved art professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and exhibitions of his artwork—often sumi-e (black and white Japanese-style brush painting) landscapes of the California coastline—had earned him recognition and respect. Letters to friends and colleagues he sent from inside Tanforan declaring his intention to create an art school reflect his unwavering determination.

The proposal for the art school was submitted to the Tanforan administration and, once approval came, Obata hurtled towards his objective. Mess Hall #6 was designated as the school’s location and enrollment forms were pasted around the camp by Obata and volunteers. The school opened on May 25, less than a month after Obata and his family arrived at Tanforan.

Kay Sekimachi, who attended the Tanforan Art School, as it came to be known, considered the school a crucial lifeline where she drew and painted every day. She described Professor Obata, whom she only knew in passing, as a “very capable person.” Capable was an understatement. Though hastily organized, Obata enlisted an impressive group of volunteers from his fellow Japanese American incarcerees at Tanforan to teach art. Among the sixteen instructors, one was a graduate of the Art Students League of New York, two had master’s degrees in architecture, four (including Obata’s son Kimio) had master’s degrees in art from Berkeley, and others were art majors and graduates of various California colleges or had attended art schools. This was a formidable group. Before Tanforan, Miné Okubo—one of the art school teachers with a master’s from Berkeley— studied art under the painter Fernand Léger while on a travelling fellowship in Europe, worked on several murals for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project, and assisted Diego Rivera on a fresco for the Golden Gate International Exposition. Obata himself was the art director of the school. He taught classes on freehand brush work, as well nature and landscape painting, and gave art lectures and demonstrations.

In the Survey of Obata Art Project, written at Tanforan, Obata listed the mission of the art school as “A. Morale, B. Fills creative need of a creative people, C. Determination to maintain one spot of normalcy.” George Matsusaburo Hibi, a fellow Japanese American artist who was a friend of Obata’s for years before they were both incarcerated at Tanforan, helped establish the art school and modeled the courses after the California School of Fine Arts, where he had taught for a time. The art school offered twenty-three classes subdivided into three categories: Fine Arts, which included landscape, figure drawing, still life, art anatomy, art lectures; Commercial Art, such as fashion design, architectural drafting, commercial lettering, and poster design; and Techniques, covering oil, pastel, watercolor, pencil, and sumi-e. Art historian ShiPu Wang’s illuminating research on Obata mentions his ability to constantly see beauty in his surroundings. Obata also tried to convey his belief in the power of art to elevate the mind to his students.

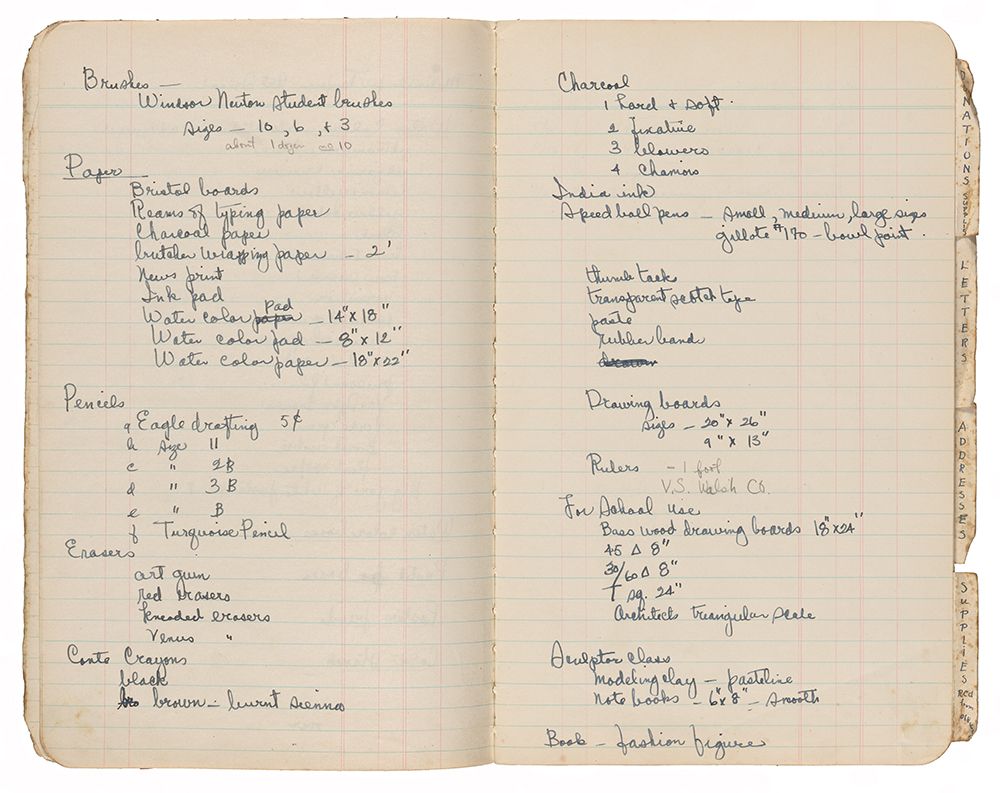

Mirroring the independent spirit of its founding, the Tanforan Art School was operated by Japanese Americans at the camp of their own initiative. The Tanforan administration required “Americanization” courses to be taught and offered nominal oversight, but otherwise did not provide any funding or resources. Instead the school supported itself financially on small personal donations from people inside the camp and a one-time registration fee of $1 per adult and $0.50 per child. The art supplies were also a combination of materials given by incarcerees from the scant personal possessions they had been permitted to bring with them and, later, mailed from the Berkeley Architectural Department (thanks to Obata’s professional connections), churches, friends living outside the camps, and activist organizations such as the American Friends Service Committee.

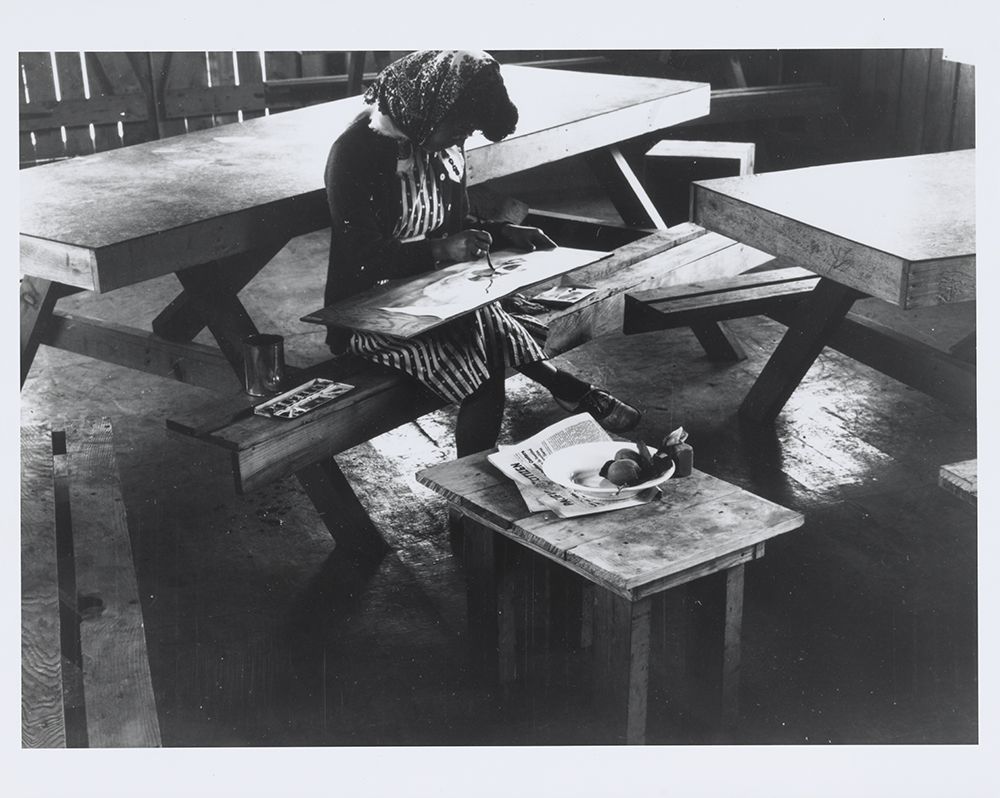

Tanforan Art School eventually had eighty-eight class sessions per week and 636 students from ages five to seventy-eight. According to the book Topaz Moon: Chiura Obata’s Art of the Internment written by Chiura Obata’s granddaughter Kimi Kodani Hill, the school offered class levels from elementary through high school, plus adult education classes. In a statement in Obata’s papers describing the art school, he wrote, “The students came at eight a.m. and classes lasted until 8 p.m. so it was the hardest job of teaching I ever had. My salary was $16 a month from the US government.” Three art exhibits were held inside the camp in July, August, and September of 1942. The final exhibit occurred before the entire population at Tanforan was forcibly removed to a different incarceration camp.

Topaz

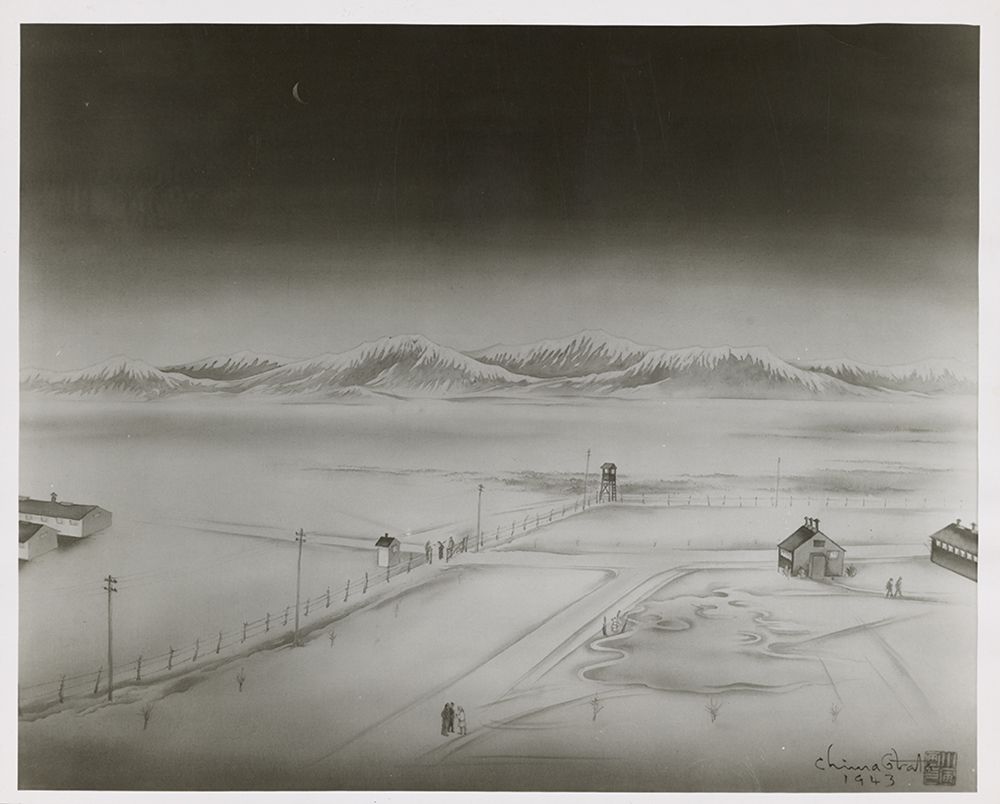

Topaz Relocation Center, as it was euphemistically called, was an incarceration camp in Millard County, Utah. Tanforan was intended to be a temporary detention center whereas the new location was meant to be permanent, but many buildings were still being constructed when incarcerees started arriving in late September. Most of the over 11,200 Japanese Americans imprisoned at Topaz came from Tanforan and the rest were from other incarceration camps, with approximately 200 people being forcibly removed from Hawaii.

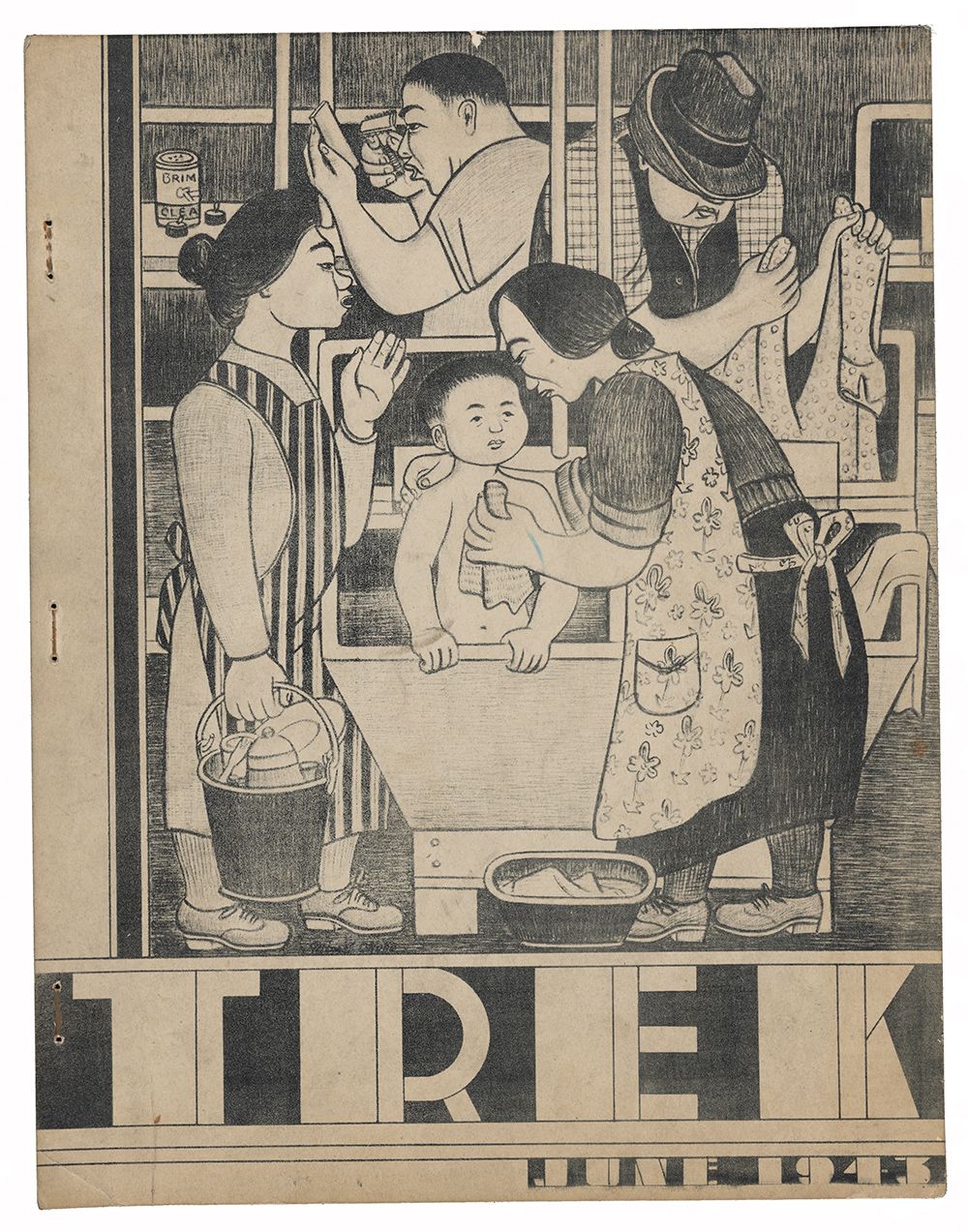

After getting permission from the Topaz administrators, Obata re-established the art school which now merged with a larger education program. The overall number of education program staff increased to over 110 and more course options were added. However, the art department was reduced to a staff of ten compared to sixteen at Tanforan. There was also turnover with some new teachers, including Obata’s wife Haruko who gave ikebana (Japanese-style flower arrangement) classes, while others, such as Miné Okubo, dedicated their efforts elsewhere. At Topaz, Okubo started working as the art editor for the literary review Trek, which was written and run by Japanese Americans in the camp, though it’s possible she occasionally taught art classes. There were exhibits of student artwork in October and staff artwork in December of 1942, then another exhibit of student work in March the following year. The art department was as pragmatic as it was ambitious and, in addition to classes, the teachers requested sewing rooms so people could make their own clothing and submitted proposals to paint murals on buildings around the camp, reflecting their desire to beautify their environment and make the camp more habitable since they did not know if or when their imprisonment would end.

Obata was director of the Topaz art department and in all likelihood would have continued that role, except for an incident that occurred inside the camp. The “loyalty questionnaire,” created by the US War Department and War Relocation Authority in 1943, was a tremendous source of controversy at Topaz and other incarceration camps. The questionnaire was distributed to assess the allegiance of the Japanese Americans and to enlist the Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans born in the US and therefore citizens, who were children of the Issei) to fight in an all-Nisei combat unit. About two-thirds of the people inside the camps were citizens. The questionnaire was especially problematic for the Issei (first generation Japanese immigrants) because Asian immigrants were denied the right to become naturalized citizens due to longstanding discriminatory legislation in the US, so renouncing their Japanese citizenship would leave them stateless. (In fact, the Issei would not win with the right to naturalization until 1952 when laws barring their path to citizenship were ruled unconstitutional.) Obata and his wife were Issei, but he and his family declared their allegiance to the US. They were subsequently viewed with suspicion by those within the camp whose resentment of the questionnaire was compounded by the injustice of their war-time treatment—some already harbored doubts about Obata’s ties to the Topaz administration in establishing the art school.

Under these tense circumstances, Obata was physically attacked while walking to his barracks one evening in early April 1943. He was hospitalized with a concussion and then was released from Topaz for his own safety, followed by the rest of his family in May. The art school continued under directorship of George Matsusaburo Hibi for two more years, until Topaz closed in 1945 and all the incarcerees were released.

After leaving the camp, the Obatas reunited with their son Gyo, who was enrolled in college in St. Louis outside the area of forced removal and thereby narrowly escaped being sent to the camps. Obata worked for a commercial art company and the family stayed in Missouri for about two more years due to intense political and public opposition to the return of Japanese Americans to the West Coast. Civilian Exclusion Orders, a series of directives created after Executive Order 9066, designated vast areas of Washington, Arizona, California, and Oregon as “military areas” where Japanese Americans were not allowed to reside, were still in effect, most until the war ended. It was not until after the order covering the Berkeley area was lifted in 1945 that the Obatas could safely return. Obata was reinstated as an art professor at Berkeley where he continued to teach until he retired in 1954. For years thereafter, he and his wife made biannual trips to Japan to lead art tours for American travelers. Obata passed away in California in 1975.

Some may question the purpose of art, but Obata never doubted its power and efficacy. In the Survey of Obata Art Project section on “Objectives,” Obata wrote that he was concerned about the effects of mass incarceration on morale, “But we became interned, having left behind our comfortable homes, careers and all our past experiences -- everybody in camps without adequate channels for mental and physical expressions.” People in the camps were restless and anxious, creating a volatile atmosphere. Obata asserted that art could provide a remedy and redirect people’s energy, helping them maintain their calm and focus. The art school was so successful at establishing order that Tanforan’s “Director of Recreation” H. L. Thompson, praised Obata in a September 14, 1942 letter. “This is to certify that the Tanforan Art School under Professor Chiura Obata has been invaluable at Tanforan. . . . Inasmuch as my job depends on having activities for 8,000 people, it was a great help to have had the Tanforan Art School take care of as many people for as long a time as it has.”

The art made by Obata, the school staff, and students served as vital documentation of the conditions within the camps, since photography was not allowed. (Images that exist from this time are mostly from journalists visiting the camps or photographers hired by the US government.) Obata made many such drawings, as did Miné Okubo, who would achieve widespread recognition and acclaim after the war for her book Citizen 13660 which contained her many drawings of life inside the camps.

Furthermore, the art schools brought together many Japanese American artists, giving them the opportunity to connect and create a strong art community. There were longtime friends like Obata and Hibi, but new relationships formed as well. At Tanforan, Kay Sekimachi took Okubo’s art classes and would become a fiber artist of renown, maintaining a lifelong friendship with Okubo which evolved from student-teacher to peers. In art classes led by fellow Japanese Americans at the Santa Anita incarceration camp, a young Ruth Asawa would get her first exposure to art. The sculptor wrote in the foreword to Topaz Moon that this was revelatory. Obata hoped to provide children and adults alike skills for coping with and eventually transcending their bleak circumstances. The art schools founded by Obata achieved this goal and opened doors for future artists. They went on to tell their stories, do their work, make their art, hoping their experience of incarceration would be remembered and not repeated.

*A Note on language: While the phrase “internment camps” is still commonly used, this blog favors “incarceration” and “incarceration camps” in recognition of the view increasingly held by historians that the word “internment,” which is legally defined as the imprisonment of “enemy aliens” during wartime, is not an accurate description of population of the Japanese Americans imprisoned within the camps. Over two-thirds of incarcerees were US citizens by birth and none were convicted of espionage or sabotage, regardless of their citizenship status. “Incarceration” is also the language currently favored by Densho, which was used as a reference for this essay. Learn more about terminology regarding the camps at these sites: densho.org/terminology/ and densho.org/sitesofshame/glossary.xml