Acquisitions: Gene Swenson Papers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Swenson_tapes_SIV.jpg)

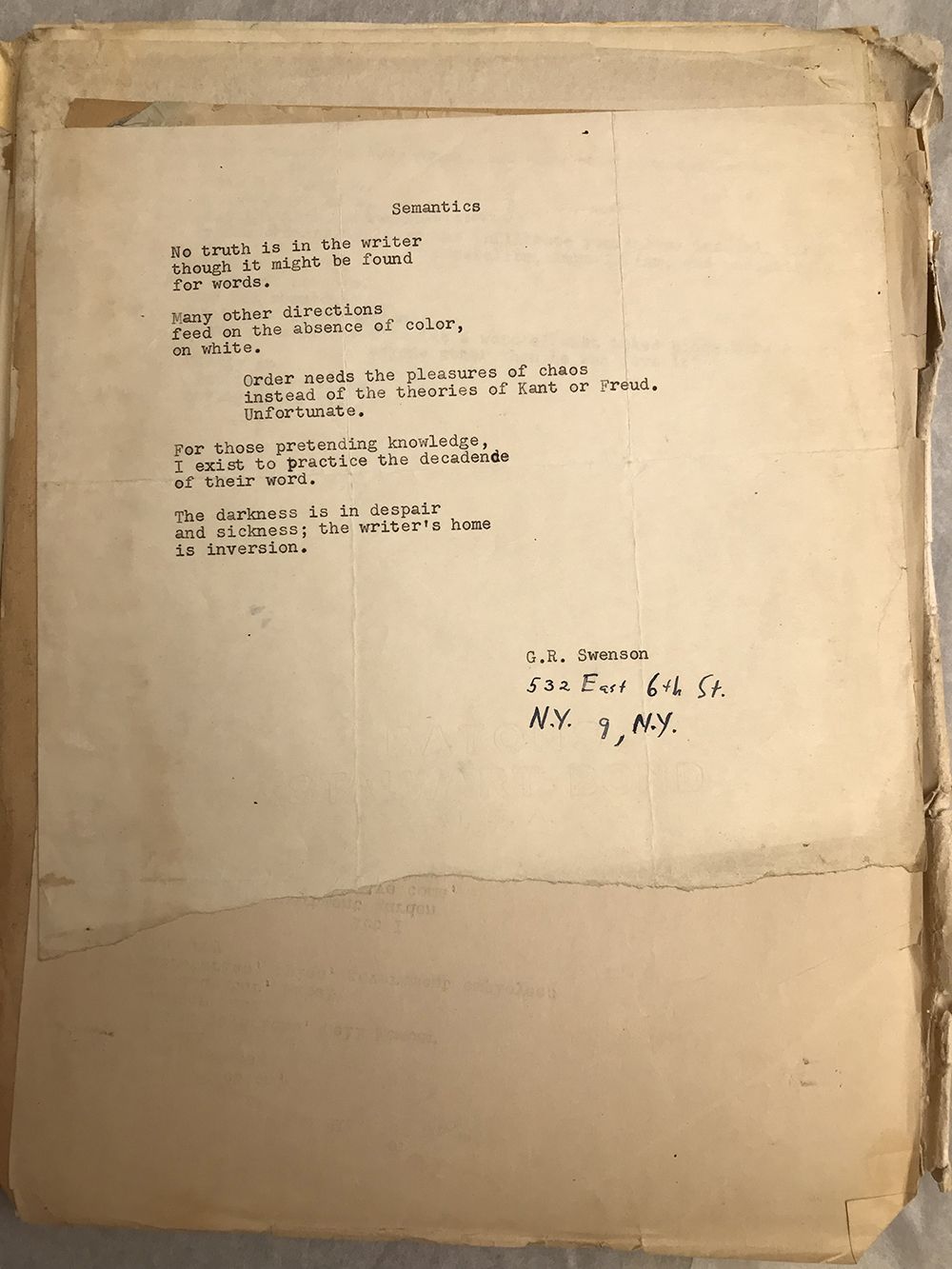

Gene Swenson (1934–1969) was an influential art critic and curator at the height of the pop movement in the 1960s. While he is best known for his contributions to mainstream art magazines like ARTnews, late in his career Swenson wrote for fringe periodicals including the New York Free Press, where he mounted a strident critique of the corporatization and de-politicization of contemporary art. His papers contain nearly two dozen notebooks and numerous files filled with writings with titles such as “Semantics” and “Art and Nature in the Paintings of James Rosenquist,” as well as print material dating from his undergraduate days at Yale University to his professional life in New York City prior to his passing at the age of thirty-five. Along with some correspondence, these materials allow researchers to track the development of Swenson’s radical ideas about the relationship between politics and aesthetics, life and art

On a loose sheet found between otherwise neatly bound notebooks, the Kansas-born Swenson recalls his hard-won realization, “I didn’t have to go on being a hick or even an innocent just because I came from [the Midwest].” Given such humble beginnings, it is remarkable that Swenson’s place in American art was built through his relationships with some of the twentieth century’s most famous artists. He had a clear impact on the American art world, as he is mentioned in oral histories at the Archives with Bill Berkson, Paul Henry Brach, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, Elaine Sturtevant, and Tom Wesselmann. Berkson describes him as “a remarkable person” who advocated for “anti-formalist” and “outsider” art. Many of Swenson’s peers lauded his 1966 exhibition The Other Tradition, which offered an alternative to the conventional narrative of twentieth-century modernism.

In 2018, art historian Jennifer Sichel, who played an important role in the Archives’ acquisition of Swenson’s papers, published a transcript of the critic’s 1963 interview with Andy Warhol for ARTnews, revealing just how much of that conversation was edited out in the magazine. We encounter, for example, an atypically unguarded Warhol laughing and stating, “I think the whole interview on me should be just on homosexuality.” Now any researcher can listen to the complete audio of this interview, preserved on several of the collection’s cassette tapes. Labels on other cassettes name additional interviewees for Swenson’s pioneering two-part ARTnews series “What Is Pop Art? Answers from 8 Painters,” including Jim Dine, Stephen Durkee, Rosenquist, and Wesselmann.

Sharply critical of large art institutions, in his final years Swenson took to the streets, famously picketing in front of the Museum of Modern Art. In one of his notebooks the critic refers to art as “disciplined love,” elaborating on this notion in relation to flower children, the “Love Generation,” and Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty. Occasionally his philosophizing takes the form of poetry, as seen in these poignant lines commenting on the nature of archival preservation and history: “Did you ever notice how / We misjudge eras / And must re-write history? / How can we, then, / See ourselves clearly. . . .” As in life, Swenson will continue to challenge the art establishment, now from within the Archives.