Nearly 1,000 Panels with 6,000 Artists: Highlights from the Artists Talk on Art Records

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Screenshot_Vernita-NCognita_Solomon-Costa-test-video_SIV.JPG)

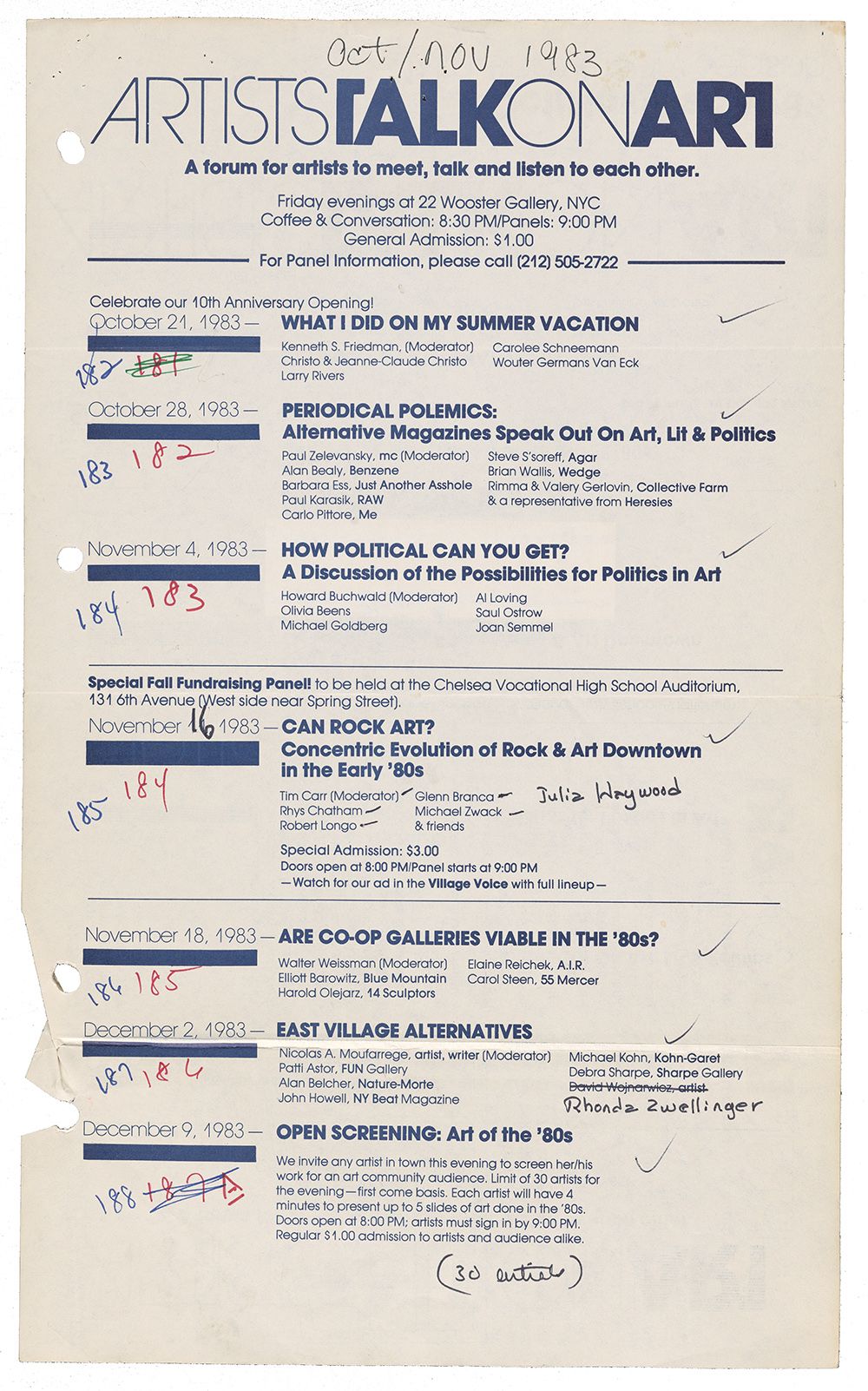

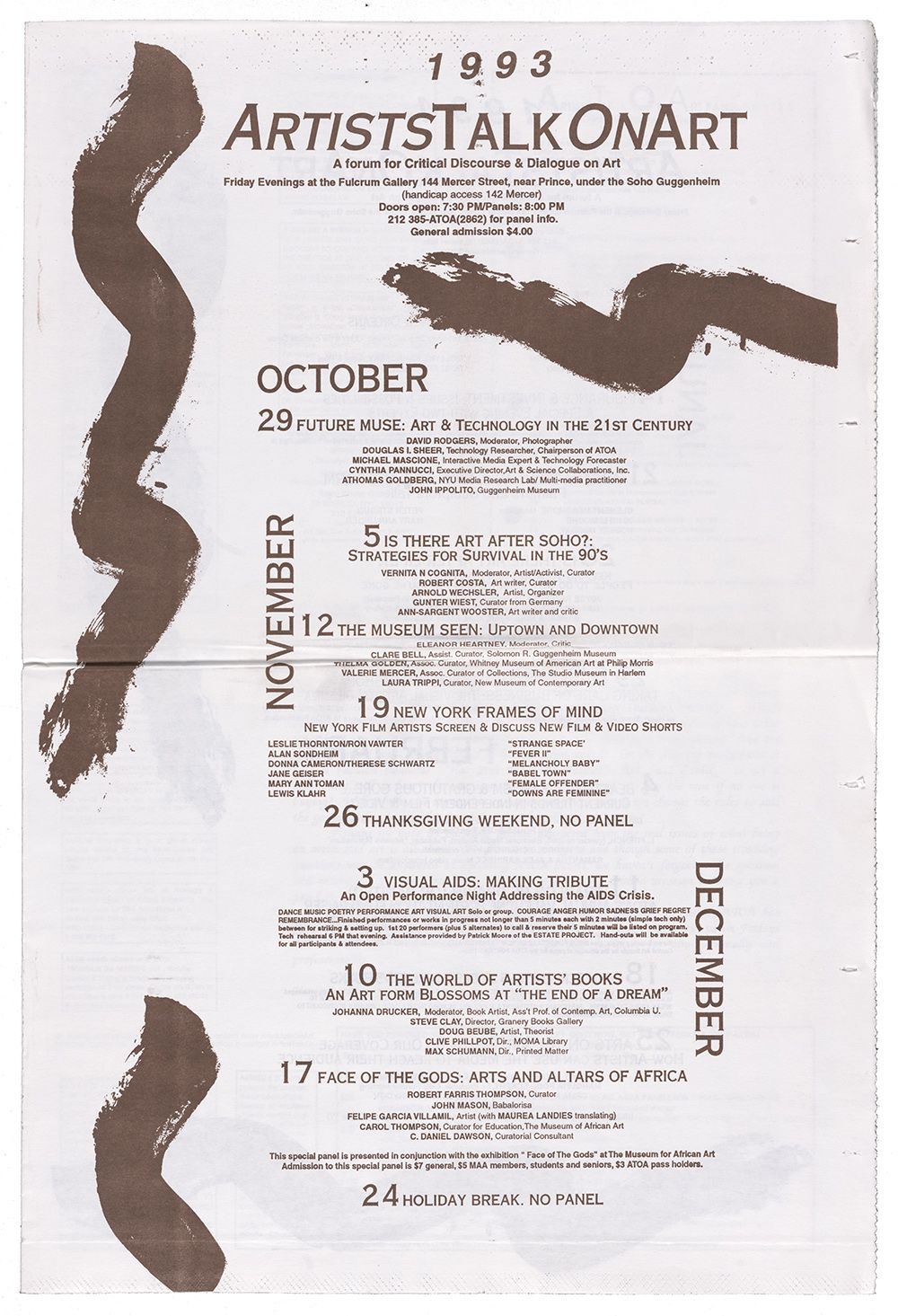

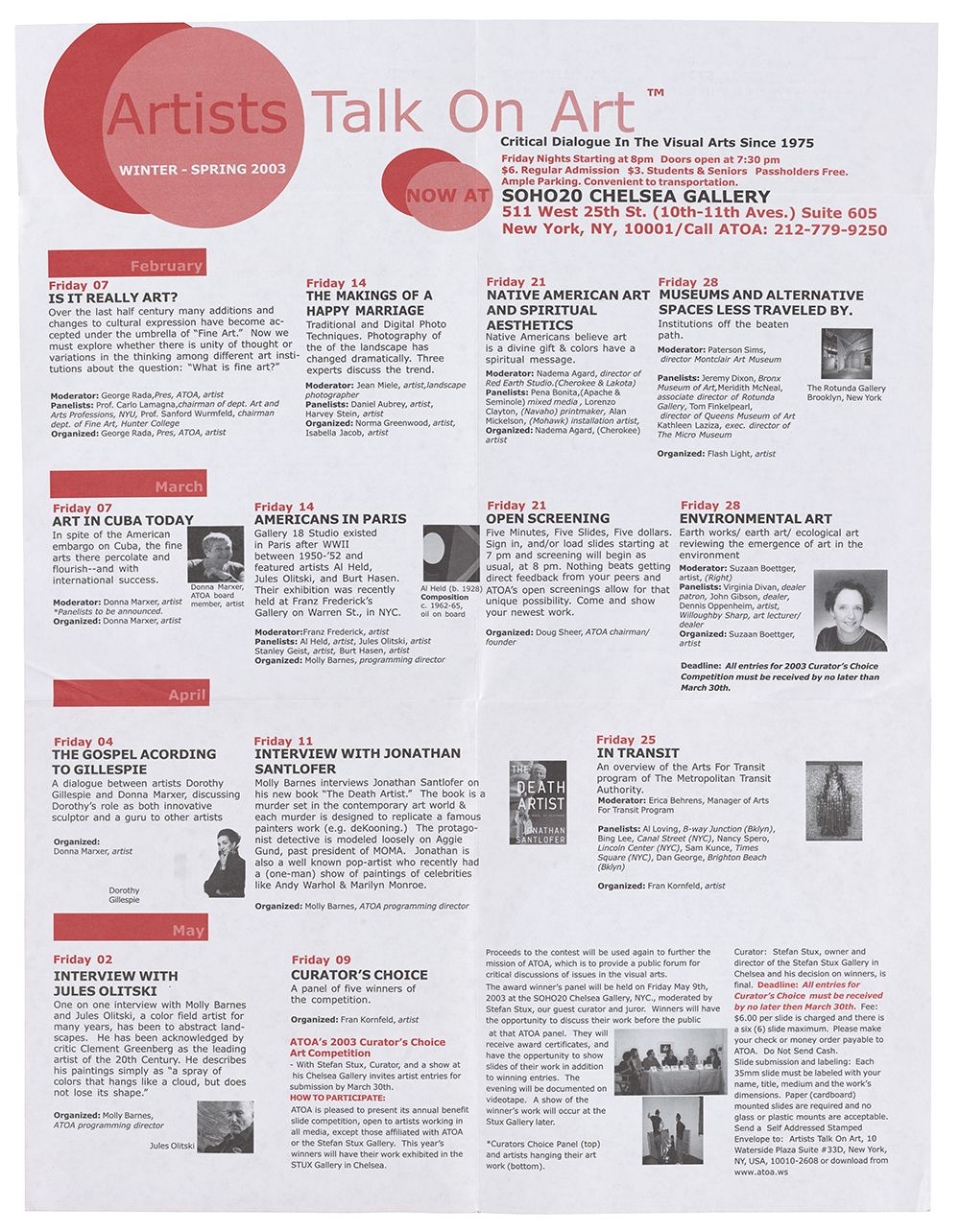

Art history can be viewed as one long conversation about art, a subject that persists in being undefined and indefinable, and the records of Artists Talk on Art (ATOA) remind us that all is up for discussion. The New York-based organization recorded Friday night interviews and panel discussions with artists, critics, and gallerists from 1975 to 2016, often opening with long-time executive director Vernita N’Cognita’s declaration “It’s Friday night in SoHo.”

The persistence of ATOA staff in independently documenting decades of these conversations is remarkable. Recording devices like smart phones are now so ubiquitous, it’s hard to remember that without substantial budgets audio visual equipment and personnel were often hard to come by in the early days of ATOA. They somehow managed it, year after year.

Recently, selected ATOA panel discussions and interviews were transcribed by the Archives of American Art for closed caption accessibility, allowing the recorded conversations to have searchable content. Audio of the 1978 panel “Artists/Punk Rockers: The Search for a New Audience” is nearly impossible to transcribe as dialogue devolves into yelling and crosstalk. The panel ends with the voice of a woman with a heavy New York accent announcing that she’s leaving because “Rehearsal starts at 11:30.” The range of the collection is broad, and the flavor of the times apparent.

Art icons like Larry Rivers, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Lucy Lippard and Kehinde Wiley represent their eras. Living links to art movements and influences expand and augment the theoretical, just what a good research collection should do. The AOTA forum is a more structured and democratic version of the abstract expressionists’ hang-out, the Cedar Bar, which we hear of from Pat Passlof, an abstract expressionist painter herself. Black Mountain College elder alumni draw a direct line to the Bauhaus via teacher Josef Albers and other émigrés and discuss its lasting effects on art education.

We hear stories of how SoHo happened, from different points of view: Art critic Anthony Haden-Guest describes explosive tensions in the East Village art community as artists like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat gained public popularity and the scene started moving towards SoHo; Holly Solomon tells of crowds suddenly flooding to her SoHo gallery; and art historian Irving Sandler addresses the skyrocketing number of artists in the city.

Discussions of traditional art materials never disappear—it’s the essential shoptalk—but we also see the early challenges of computer-assisted work, with questions of access and influence. Panels pop up with titles like “Is There Still Life In Still Life?” as artists ride the waves of trends and of their own particular dedication.

Diverse voices are represented. Artists of color frequently respond with grace under pressure to what we now see as implicit bias in audience Q & A sessions. Mohawk artist Alan Michelson eloquently questions the European definition of aesthetics as an appreciation of beauty, since the beauty of Native peoples and their arts were invisible to settlers. Carolee Schneemann, a pioneer of interdisciplinary thought who used her nude body as media, poignantly chalks up her unemployability to her edgy performances, while women working in craft mediums like embroidery describe their uphill battle to be taken seriously as artists.

Panel questions like “Is Elitism an Issue in Art Today?” or “Should We Leave New York?” represent the intellectual activity that art world discussion can stimulate. We could spiral around to these same topics today: “Does Art Reflect Society? How So?” or “Art and Science: Marriage or Divorce?” We witness the practical problem of studio space in New York City, with changing loft laws. There are discussions around how to obtain health insurance, how to be sure that your materials are safe to use, and understanding what happens to your work if something happens to you. Discussions cover the art itself and the theory, but also the hustle.

We have a glimpse behind the isms, and movements not quite settled on, with “polyartistry” a suggested term for emerging boundary-crossing interdisciplinary work, or movements that didn’t quite take off (“Cro-Magnon Art Then & Now: Its Applicability for Today”).

Artists Talk on Art donated both media originals and more than forty terabytes of digitized surrogates to the Archives for preservation, along with decades of flyers. This collection is a reminder that we live in a world of time-based media—film, video, and audio are the water we swim in—and we don’t always recognize its importance and fragility. These discussions about art address the deep questions of the times, examining politics or psychology or art history itself in ways that remind us that artistic subject matter contains all disciplines as a field of inquiry. These rich recorded conversations sit in time on the cusp between analog and digital, and their inclusion in the Archives of American Art ensures their survival.

This essay originally appeared on the Archives of American Art Blog.