Conversations Across Collections: Oscar Bluemner in Color

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/CB-Bluemner_blueosca00024_detail_SIV.jpg)

Welcome to Conversations Across Collections, a collaborative series between the Archives of American Art and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, where we highlight archival documents and works of art from our collections that tell the story of American art. Read more on Oscar Bluemner in Larissa Randall’s essay, Conversations Across Collections: Oscar Bluemner’s Self-Portrait is Anything But Simple, on the Crystal Bridges blog.

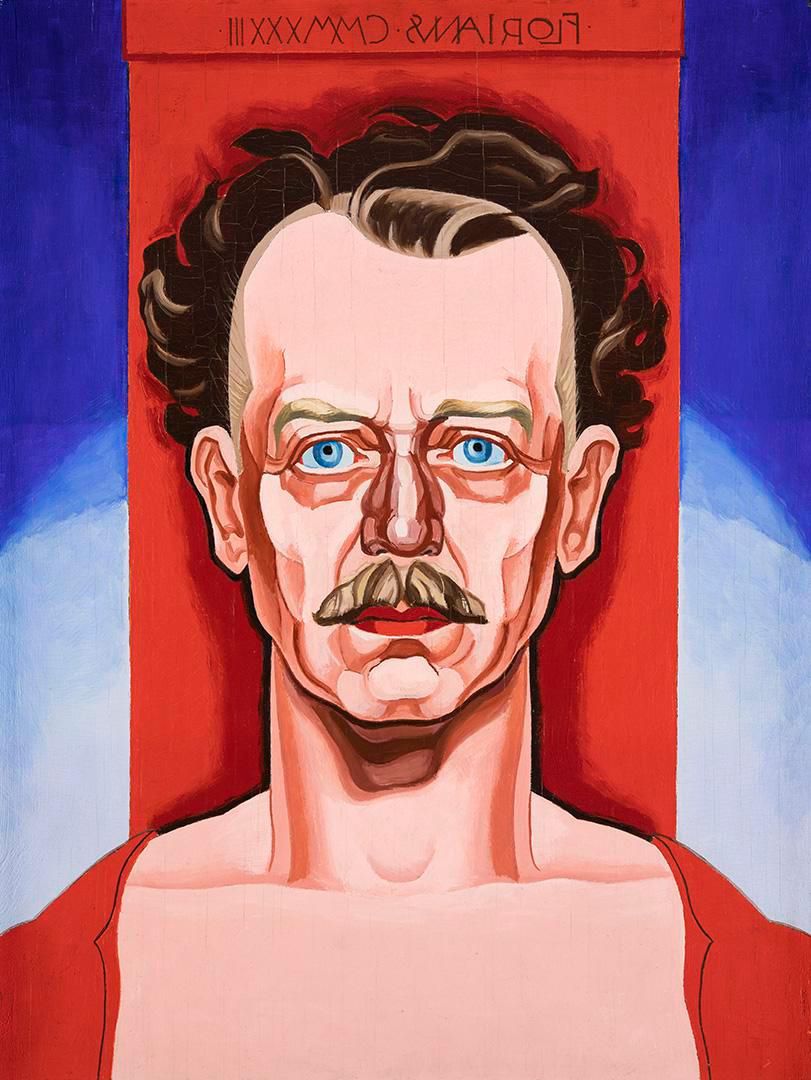

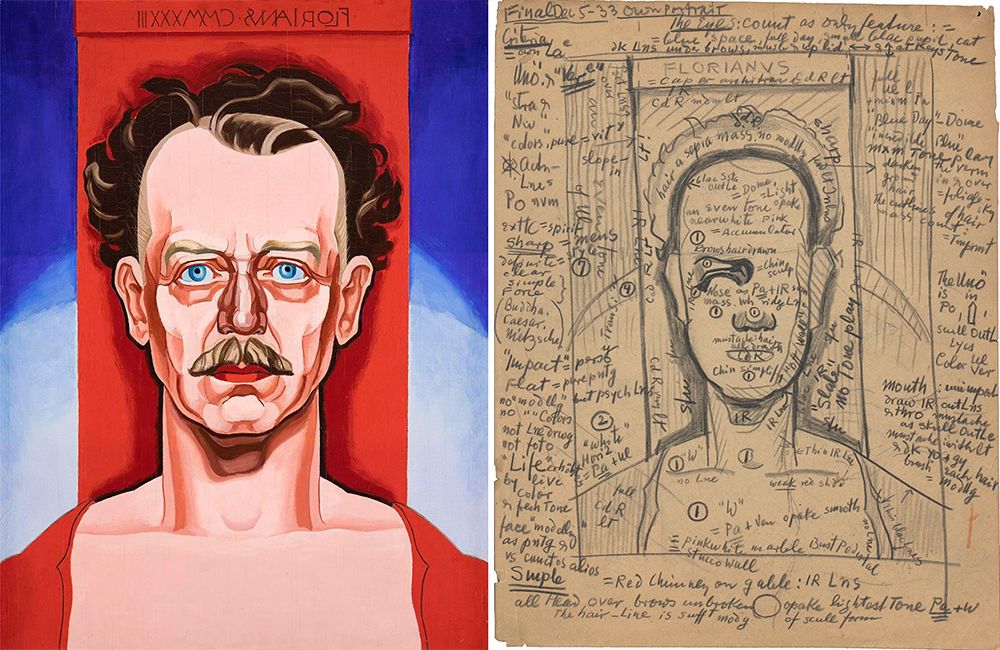

Oscar Bluemner’s Self-Portrait (1933) is a curious painting. Bright and sculptural, the colors nearly vibrate with intensity. His chiseled head and chest are set against a chimney-like backdrop and loose cloak in Bluemner’s signature color, vermillion. At the cap he inscribed, “Florianus CMMXXXIII” in reverse—his adopted middle name, derived from the Latin flos, meaning flower, paired with the date of the painting, 1933. The reversed letters and roman numerals foreground his method of using a mirror to study his likeness. He stares, head-on at the viewer. His blue eyes resonate with the celestial orbs of white-to-ice-to-deep-blues in the open-ended space beyond the sharp, red slab, the whitish semicircle creating a halo effect around the solid sitter and a tension between earth and infinity, warm and cool, matter and spirit, life and death. His skin tone—a vermillion tint—almost seems lit from within, glowing, vibrant.

Bluemner devoted most of his life to the study of color and the moods that color excites, expressed predominantly in his bold landscape paintings. In 1932, he applied for, but did not receive, a Guggenheim Fellowship. The failed application marked his life’s progress to that point: “For forty years, I have made, in every possible way, a constant, thorough, systematic, and complete study of the history, literature, and scope of color, of its theories, materials and applications.” He sought funds to sustain his passion, “to paint a series of unusual ‘color themes’—in landscape form.”

The following year, at age sixty-six, Bluemner painted his self-portrait. Why did Bluemner depart from his landscapes to paint such a striking, confrontational likeness? The answer is simple: in late 1933 the Whitney Museum of American Art announced that it was having an exhibition of self-portraits by living American artists and Bluemner, whose work had been exhibited at and purchased by the Whitney, could not resist the challenge. On October 3, 1933, he wrote in his painting diary, “I wanted to take a rest, a vacation in New York and draw from the brown red November new imagination of white, black and brown reds, oxids of iron. But the news of the Whitney Museum to hold an artists selfportrait show next Lent caused me to paint mine.”

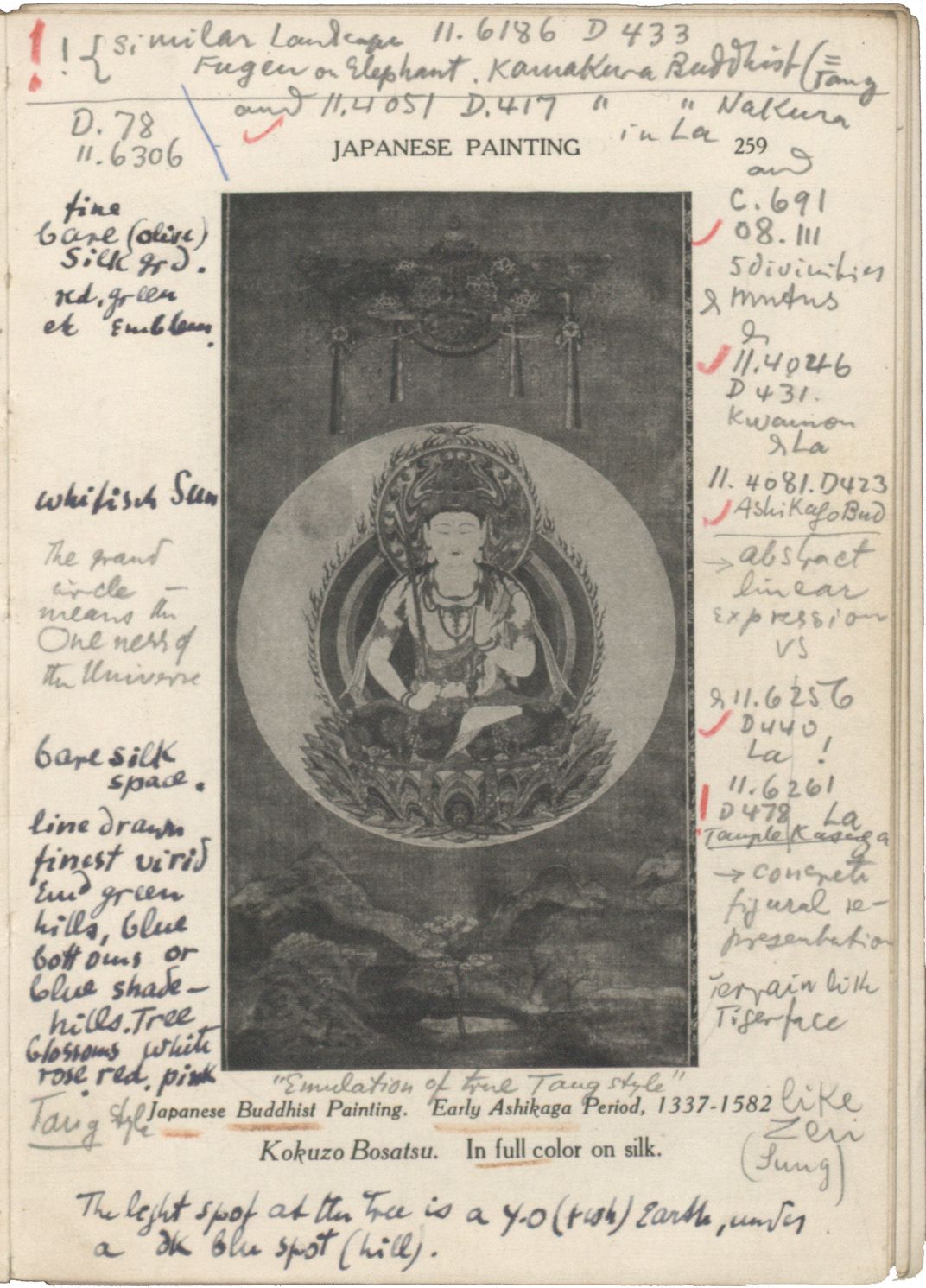

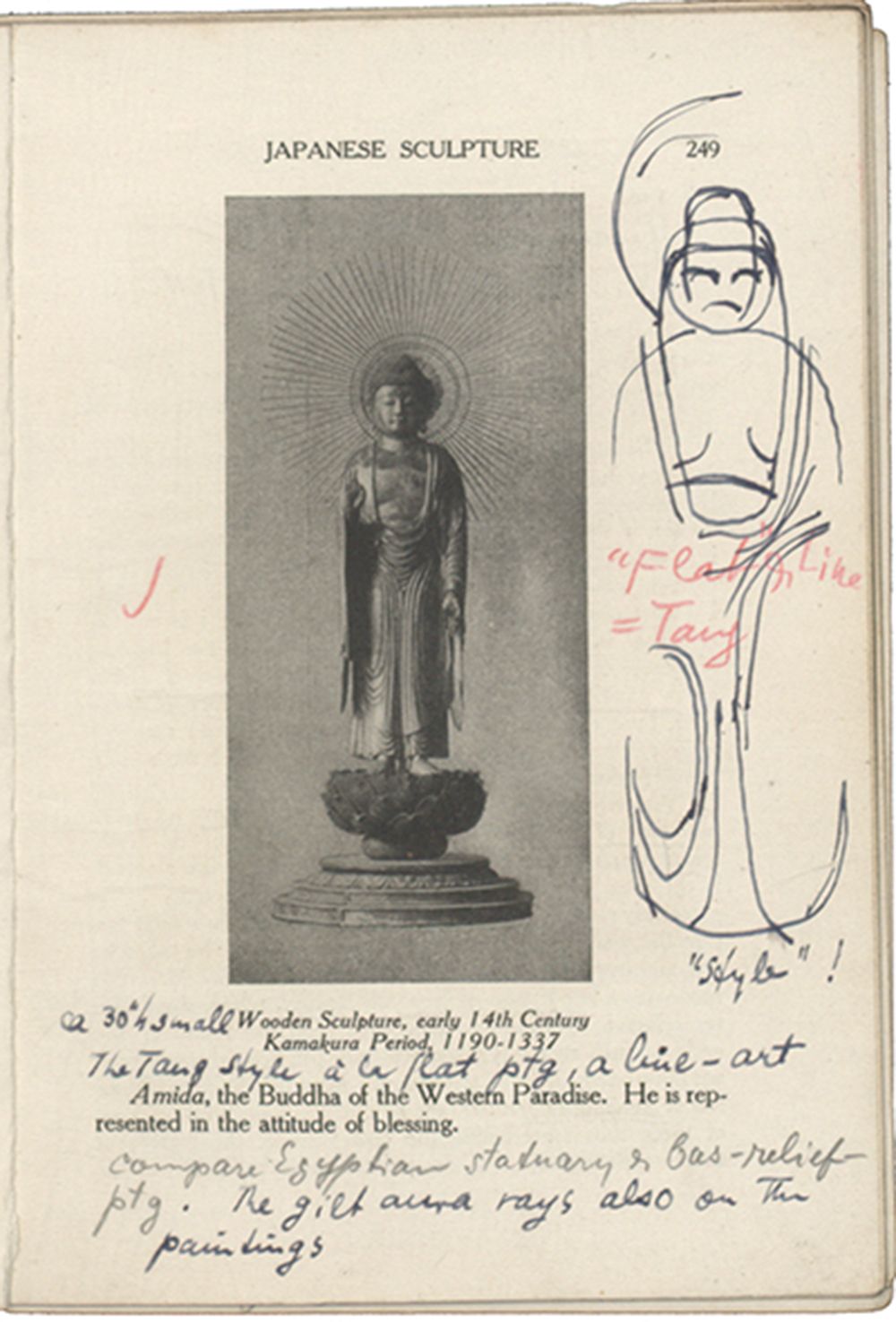

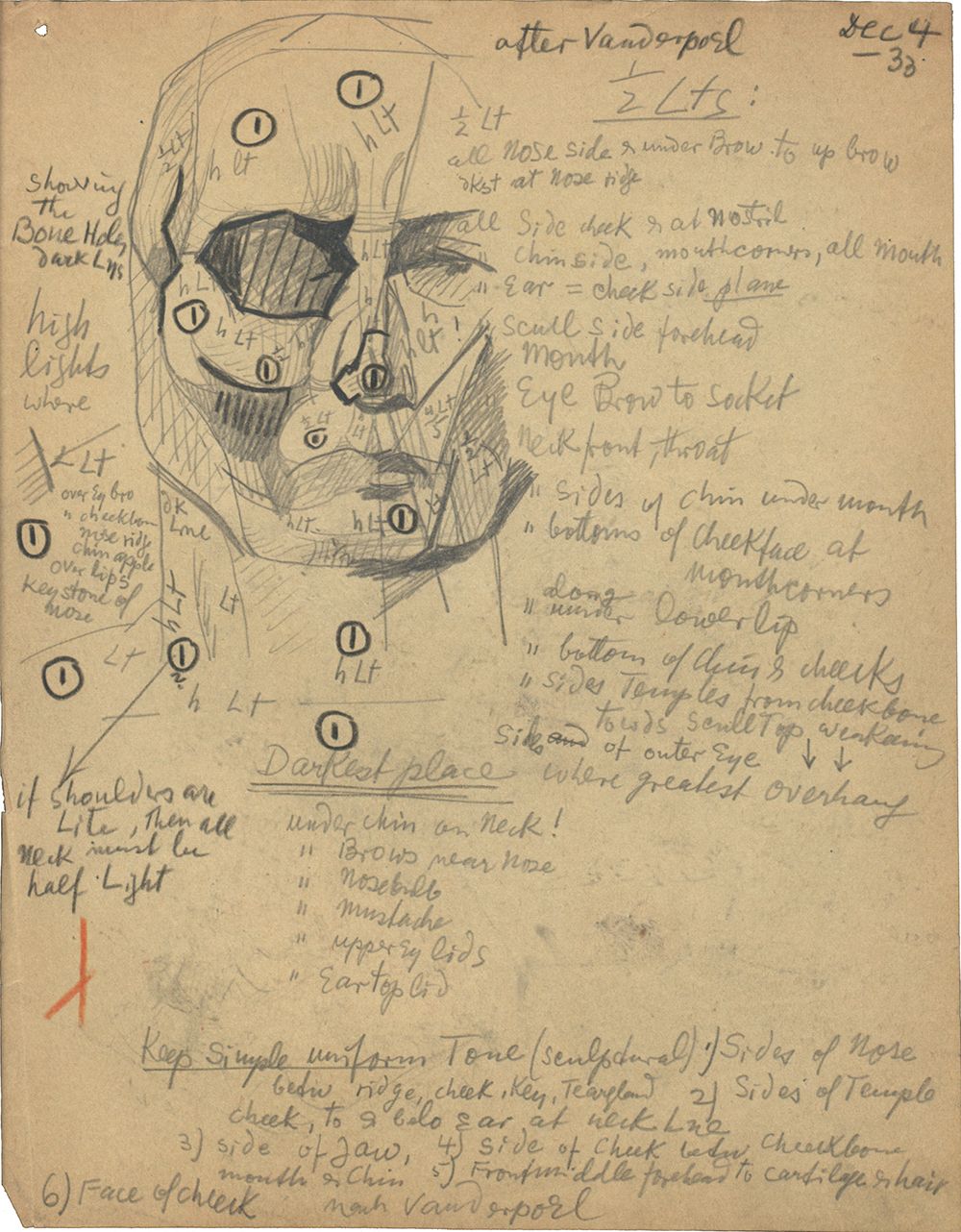

Bluemner’s copious notes for his Self-Portrait, part of his 1933 painting diary found among his papers at the Archives of American Art, prove that he went about the task with characteristic diligence: “I studied, measured, drew a number of drawings, sketches, of my face, with a 10 cent poor mirror, string, ruler, triangle copying and tracing paper, notes and Vanderpoel’s book, human figure, Normal Diagram of faces, 1893 Berlin, e.t.c.” He considered the portraits of Hans Holbein and Albrecht Dürer, but dismissed them as “drawing fotographer[s].” And while Bluemner praised Frans Hals as a master draftsman, he rejected his finished portraits as “just paint.” Instead Bluemner was drawn to the symbolic power of Chinese and Japanese art. In his personal copy of the Handbook of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston: Chinese and Japanese Art (1907), he noted in the margin next to an image of Kokuzo Bosatsua: “whitish sun, the grand circle means the otherness of the universe.” Bluemner admired the emblematic use of line and color, and the flatness of the picture plane, particularly in representations of Buddha, and registered that his self-portrait was a “simplified Buddha head—illustration of a sculpture.” In the same well-worn handbook, beneath a wooden sculpture of Amida, the Buddha of the Western Paradise, Bluemner commented that the Tang style was like a “flat painting” and made his own sketch in the margin—the open robe and exposed collar bone like the 1933 Self-Portrait.

Buddhas aside, a key technical source for Bluemner was John Henry Vanderpoel’s primer for art students, The Human Figure, published in 1907, which included detailed instructions for drawing the eyes, nose, mouth and chin, ear, and head, along with Vanderpoel’s illustrations. Bluemner dug in, embracing Vanderpoel’s dictum: “The head is composed of six planes,” which Bluemner enumerated in his notes. He also followed Vanderpoel’s advice to “illuminate the head with a narrow and single source of light” to reveal those planes in three-dimensional space.

Bluemner’s process took three weeks—from November 30, 1933, when he primed and sanded a 15 x 20 inch 3-ply fir panel, to December 23, 1933, when he touched up the tones. On December 22, he heightened the sculptural planes of his face, using white and vermillion red as “‘flames’ running up cheeks & temples,” for “impact” and “energy.”

It’s not surprising that Bluemner thought of his self-portrait as a landscape, noting, “It is a portrait as a scene.” He added, “The red, vermilion light, compels a pure reddish flesh color, venetian + white, instead of yellowish tones. The blue sky repeats in the eye. Black hair as mere mass, like foliage, better than my brunette hair.” In his painting diaries, Bluemner often contemplated the symbolic duality between a portrait and a landscape, “landscape painting is semi self portraiture,” he wrote on August 10, 1929.

Early in 1934, the Whitney did indeed hold an exhibition of self-portraits by living American artists along with the museum’s acquisitions of 1933, but Bluemner’s portrait was not in the exhibition. Instead it appeared at the Morton Galleries at 130 West 57th Street, from late January to mid-February 1934, among paintings by Clarence Shearn and watercolors by Gregory D. Ivy.

Considering that Bluemner painted his self-portrait with the Whitney Museum of American Art in mind, the red, white, and blue may overtly signal his allegiance to the United States. Bluemner, who emigrated from Germany to the US in 1892, and became a naturalized US citizen in 1899, was no doubt aware of Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 and the loss of personal freedoms in his homeland. In his notes he wrote, “The blue sky, away from money slavery and slave drivers, the brilliant sunlit red wall of a small owner’s lot in a free country, red and blue as a theme, versus omnes alios [against all others].”

As if bracing for negative criticism, Bluemner wrote, “. . . to hell with all that anybody, ‘artist,’ critic, or buyers, say about my work.” Happily, for Bluemner, the painting received high praise from critic Margaret Breuning in the New York Evening Post, January 1934. “Also at this gallery, a portrait by Oscar Bluemner is on view,” she wrote, “It is not labelled ‘Self-Portrait,’ yet its physical lineaments and psychical aura can belong to no other than this artist who has absented himself lately from local galleries. I think Mr. Bluemner has never executed a better piece of work; even his passion for red has been subdued to décor and enhancement of the vigor of the almost vehement characterization.” Bluemner clipped and saved the review. Circling Breuning’s appraisal with a grease pencil, Bluemner added a gleeful exclamation mark beside the copy!

He also clipped and saved Henry McBride’s comments from the New York Sun, January 27, 1934: “He [Bluemner] takes portraiture very seriously and is his own severest task-master. Constantly while he was doing the work he saw things that he wished weren’t there, yet conscientiously, he put them down. He put them down with force and precision and in the end achieved a commendable piece of work.” In that flurry of positive press, Bluemner also kept a feature article by Richard Beer, “Bluemner Quitted Architecture for Life of ‘Vermillionaire,’ Forfeiting Assured Rewards for Artistic Convictions,” from The Art News, February 24, 1934. Calling out Bluemner’s precarious financial future as headline news, the text framed a prominent reproduction of the self-portrait. Though Beer didn’t mention the painting, he commented on Bluemner’s earliest exhibition in Germany, at age eighteen, of portraits.

With his 1933 Self-Portrait, Bluemner returned to his teenage practice of portraiture now transformed by his intensive, forty-year study of color theory, imbued with Chinese and Japanese influence, formal figure studies, and a burning desire to be recognized as an American artist with a unique vision. Oddly enough, for an artist obsessed with color, he noted that color was not the driving force when painting a portrait: “Resemblance, truth is all in proportions. In a portrait Color is unimportant. Life like effect is in keen sharp accurate drawing.” Though keen, sharp, and accurate, Bluemner’s Self-Portrait is emotionally alive with color.

Explore More:

- Conversations Across Collections: Oscar Bluemner’s Self-Portrait is Anything But Simple, by Larissa Randall on the Crystal Bridges blog

- Oscar Bluemner's 1933 Self-Portrait at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

- The Oscar Bluemner Papers at the Archives of American Art.

- “The Human Landscape: Subjective Symbolism in Oscar Bluemner's Painting,” by Frank Gettings in the Archives of American Art Journal, vol. 19, no. 3, 1979 via JSTOR or The University of Chicago Press

- Past entries in the Conversations Across Collections series