Conversations Across Collections: Talking With Marisol

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/AAA_forbrobi_1928131_detail.tif)

Welcome to Conversations Across Collections, a collaborative series between the Archives of American Art and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, where we highlight archival documents and works of art from our collections that tell the story of American art. Read more on Marisol in Meg Burns’s essay, Conversations Across Collections: The Journey of Marisol’s “The Bathers,” on the Crystal Bridges blog.

As the Philadelphia Project Director for the Archives of American Art from 1985–1991, I conducted and edited many oral history interviews and found the process fascinating and revealing. Not surprisingly, most of the subjects (artists, gallery directors, and collectors) were forthcoming, taking advantage of an opportunity to lay some groundwork for their legacy. One of the things I found most compelling about the interviews were the revelations of the sitters’ personalities, which can contribute to a deeper understanding of their art, business, or collecting.

The interview was an important source for understanding Marisol, both personally and professionally, for the exhibition and catalog, Marisol: Sculptures and Works on Paper, that I completed for the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art in 2014.

Born in Paris in 1930 to Venezuelan parents, Marisol was raised between Venezuela and the United States. She was primarily understood as being inspired by the art of New York and Europe, with little interest in her indebtedness to the art of her native country. Among her personal papers (now in the collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery), are postcards with images of abject dolls made by the Venezuelan artist Armando Reverón (1889–1954).

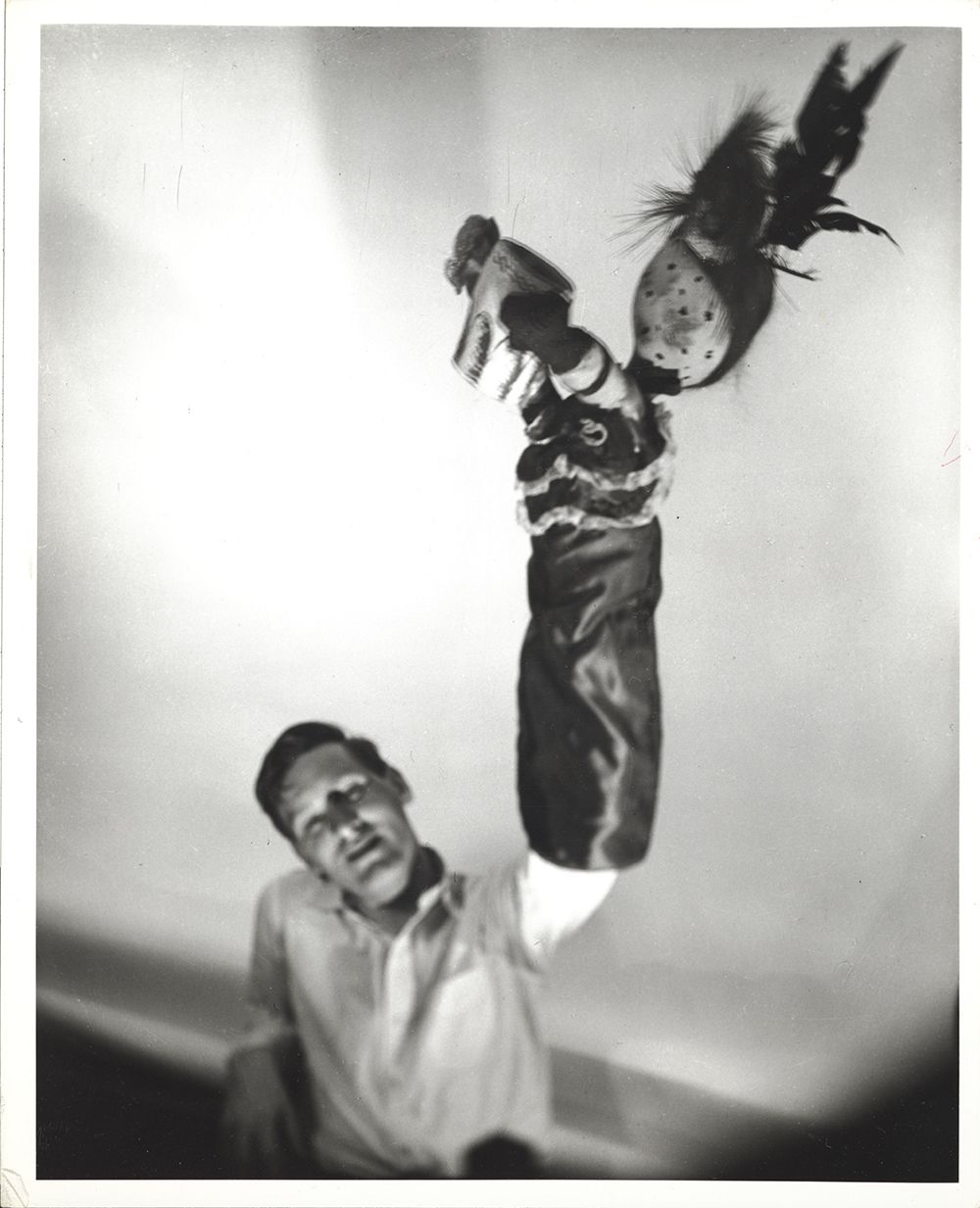

Marisol repeatedly made handmade dolls, some of enormous scale, and a search for a direct connection between the two was resolved by the interview. She discussed her mother’s friendship with Reverón and a visit to him when she was a child after “he decided to retire from society, to live like a hermit,” in a remote house he built that was like a Tarzan movie with a tree house and monkeys; she also notes his art making with burlap and paint made with dirt. Besides the shared interests in dolls, Marisol too fled, in both the late 1950s and late 1960s, when her career became overheated.

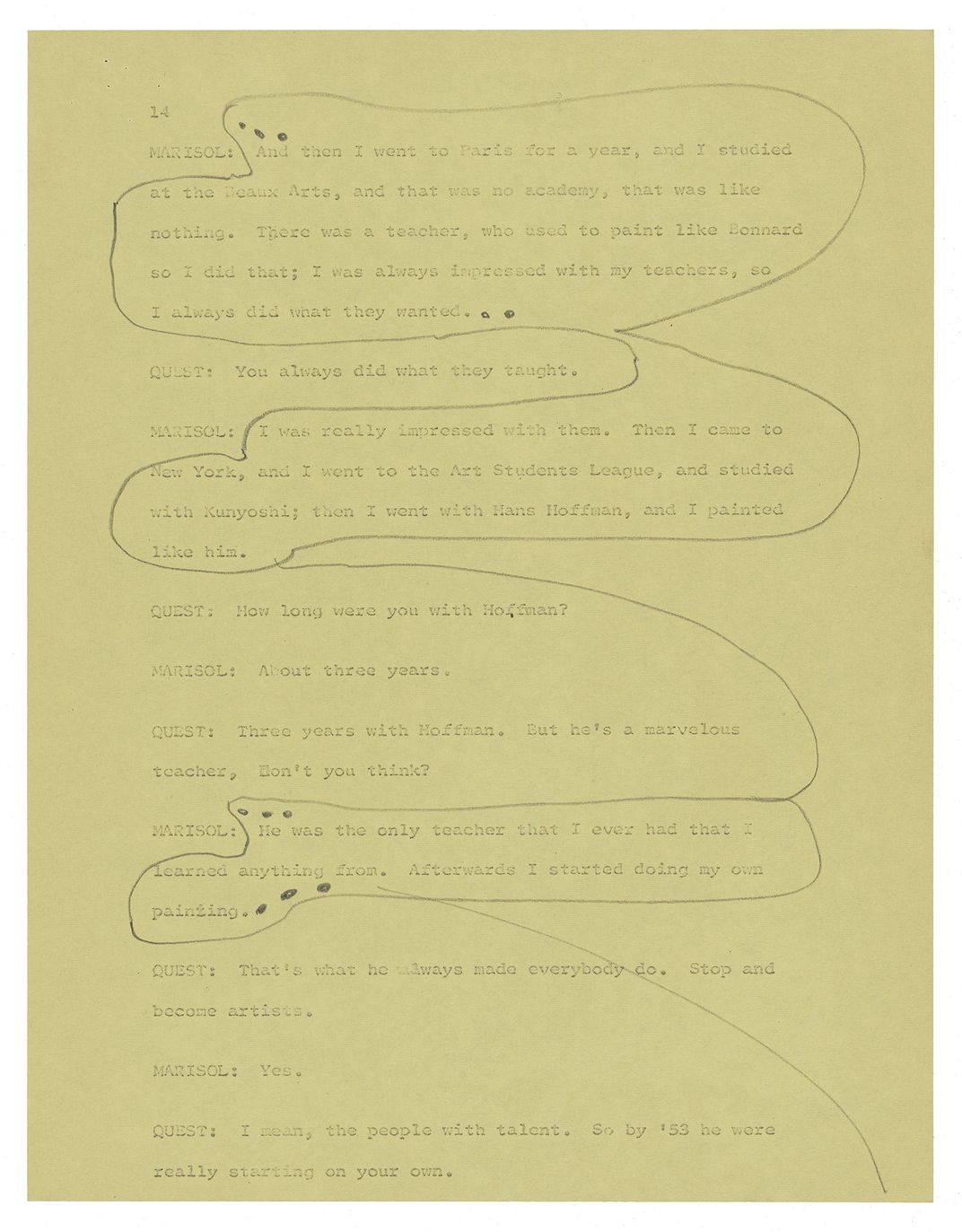

The transcript has sections that have been circled to highlight particular subjects as if for publication. A good example is her discussion of how important her studies with Hans Hofmann were for her artistic development. “He was the only teacher that I ever had that I learned anything from. Afterwards I started doing my own painting. . . . But I gave up painting and started to do small sculptures. . . . About ’53.” Marisol’s studies (1952–55) in both New York and Provincetown are documented in the Hans Hofmann papers, which also help track her travels between Mexico and New York City during the early 1950s. Her studies with Hofmann and the shift to sculpture are significant to her ultimate artistic development.

Having interviewed Marisol myself, I found she could be frustrating because of her reticence, but also very funny, as evidenced in the Myers transcript. At one point during a discussion about Hofmann’s school and being forced to paint abstractly, Marisol interjects “Could there by a few more things today that I haven’t said before? Every time I find something else. It’s like going to the psychiatrist.” Grooms starts to address the difficulty of doing interviews and to scotch the diversion Myers quickly shifts gears to talk about their early exhibitions, including Marisol’s first show at the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1957. Castelli understood the importance of documenting the gallery’s exhibitions and provided evidence of the range of Marisol’s early sculptures that sit on pedestals or hang on the walls like paintings.

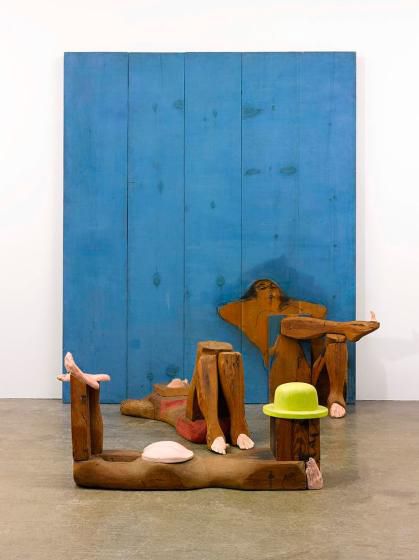

Another revealing section begins with Myers noting that there was a strong theatrical feeling running through her exhibitions at the Stable Gallery (1962 and 1964). Grooms too agreed that her exhibitions had a strong theatrical flavor. She pushed back saying that she was using the space. She recalled that when going to museums, she didn’t look at sculptures on pedestals, “I always overlooked it, but I wanted the thing to be so overwhelming, part of the environment, the people become a part of it too.”

This impulse is evident in works such as The Bathers (1961–62). On the one hand, it is a common enough scene with three figures in typical sunbathing postures. But on the other hand, those figures spread out into the gallery space transforming the viewer into a fellow beach goer picking their way across the sand. The scene is characteristic of Marisol’s disruptive, yet playful, signature style that mixes drawing, paint, plaster casts, and found materials in creating figures that shift between two and three dimensions. Details like the plaster feet and buttocks of the woman with the yellow hat are beguiling—which helps explain why her exhibitions were so popular. Her 1964 Stable Gallery exhibition reportedly attracted 2000 people a day including mothers with children. Marisol’s studies with Hofmann and his famous dictum of the push pull of paint are exploited in this expansive and humorous trip to the beach—no pedestals necessary.

There are other sections that provide useful information and give a sense of her personality, that is well reflected in her work. But the very last line of the interview is Marisol’s and I think it is a fitting place to end. “It is very interesting to do all this talking. I think we should stop now.”

Explore More:

- Conversations Across Collections: The Journey of Marisol’s “The Bathers” by Meg Burns on the Crystal Bridges Blog

- Marisol, The Bathers, 1961-62 at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

- “A Conversation with Marisol and Red Grooms,” in the John Bernard Myers papers, circa 1940s-1987.

- Oral history interview with Marisol, 1968 Feb. 8.

- Past entries in the Conversations Across Collections series