New Collections: Nela Arias-Misson Papers

The papers of Cuban-born, modernist painter Nela Arias-Misson are now at the Archives of American Art

:focal(547x375:548x376)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d9/58/d95842bf-35ae-4118-a125-3a1241e6ad68/fall_2021_franco_fig_1_for_blog_detail.jpg)

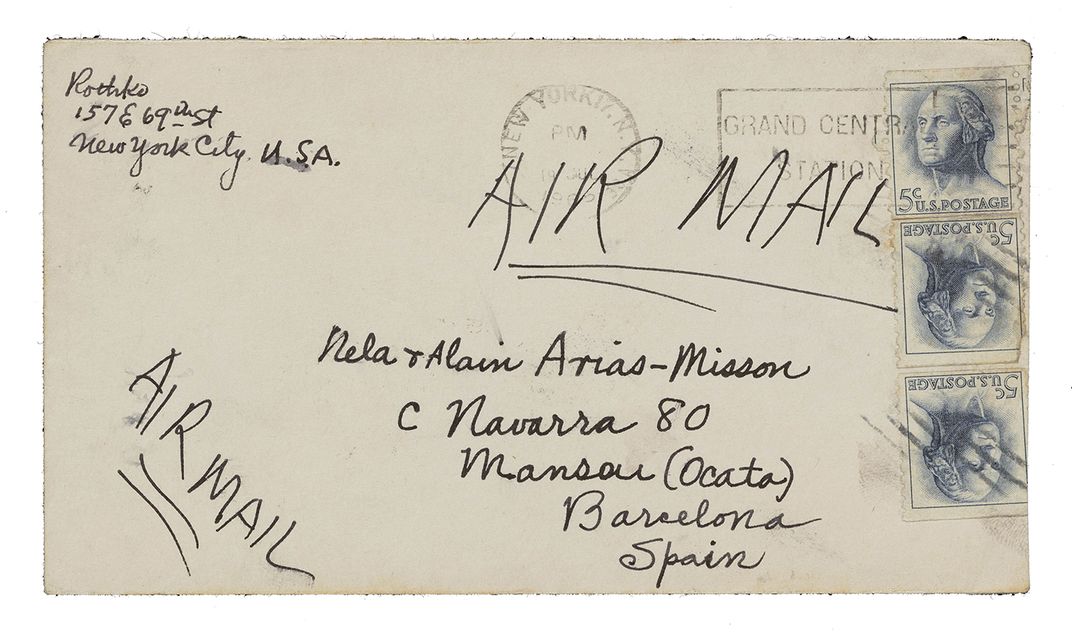

Every new collection alters the historical record, but not all impact the most entrenched concepts typically relied on to narrate American art history. With the first installment of the papers of painter Nela Arias-Misson (1915–2015) now at the Archives, researchers can look forward to revising histories of modernism, abstract expressionism, and minimalism. Charismatic, and dedicated to the continual evolution of her style, Arias-Misson crossed paths with Mark Rothko, Hans Hofmann, Antoni Tàpies, and other leading avant-garde painters. The impression she left on them is evident in correspondence, photographs, and other documents in her papers.

A 1965 letter from Rothko begins with gratitude to Arias-Misson and her husband Alain for their “beautiful little poems” and elicits the poetic in Rothko as well, who pens poignant lines such as, “It is good to hear that you are settled and that in your new home you find the kind of a world in which you no longer feel alien and where you can work. As one gets older and reaches my age the yearning and hope for such a place is given up and one creates a solitude which one abhors and holds on to with all his strength.” In photographs of Arias-Misson’s studios and early exhibitions, one can see that she worked through visual forms associated with Rothko. These photographs and others come meticulously arranged and researched by Marcelo Llobell and Flor Mayoral, executors of Arias-Misson’s estate and cofounders of the Doral Contemporary Art Museum in Florida.

Arias-Misson’s substantial relationship with the influential teacher Hofmann, whose papers also reside at the Archives, is documented through photographs of classes in session, gallery openings, and social gatherings with Hans and Maria Hofmanns’s Provincetown circle. A letter from Maria to Tàpies, introducing Arias-Misson to the artist, demonstrates the promise Hans saw in his student. “A friend and student of Mr. Hans Hofmann will go to Barcelona for a while and she would like very much to meet you and also other artists,” she wrote in 1961. “We would be happy if you could help her to see the interesting life there.”

Also important to Arias-Misson’s artistic development was her exchange with the Spanish diplomat José Luis Castillejo. While conducting his state duties, including as ambassador to Nigeria and to Benin, Castillejo wrote art criticism. The typescript of a 1966 essay that he sent to Arias-Misson for review positions her within the era’s central emergent movements. Castillejo asserts, “Some of Nela Arias-Misson’s works are . . . a meaningful step in the direction we are working today, towards a minimal, zero art. . . . Literal art is a better word than minimal art. Reductive art is confusing. . . . Literal painting [is] the best name that occurs to me.” Such writing and Arias-Misson’s work reopen for investigation these familiar terms describing art of the 1960s.

Despite the considerable attention Arias-Misson received from peers and critics in her lifetime, she remains understudied in scholarly narratives concerning artists working in the US in the 1960s. Her papers show how the history of this important period in American art can be retold if we place at its center a Cuban-born woman and the network she forged across North America, Latin America, and Europe.

This text originally appeared in the Fall 2021 issue (vol. 60, no. 2) of the Archives of American Art Journal.