COOPER HEWITT, SMITHSONIAN DESIGN MUSEUM

How National Design Award Winners Are Fighting The Pandemic

As the world grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic, National Design Award winners Design that Matters, threeASFOUR, and Open Style Lab are working to increase access to personal protective equipment for medical workers and face coverings for civilians. This article highlights their distinct strategies.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/IMG_20200325_101635-scaled.jpg)

As the world grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic, National Design Award winners Design that Matters, threeASFOUR, and Open Style Lab are working to increase access to personal protective equipment for medical workers and face coverings for civilians. This article highlights their distinct strategies.

Design that Matters

In 2012, Design that Matters (DtM) received a National Design Award in recognition for creating products and services to meet the needs of poor people in developing countries, such as Firefly, a cost-effective device to treat newborn and infant jaundice in rural hospitals, and Kinkajou, a rugged tool that provides lighting and reading materials for night time literacy classes.

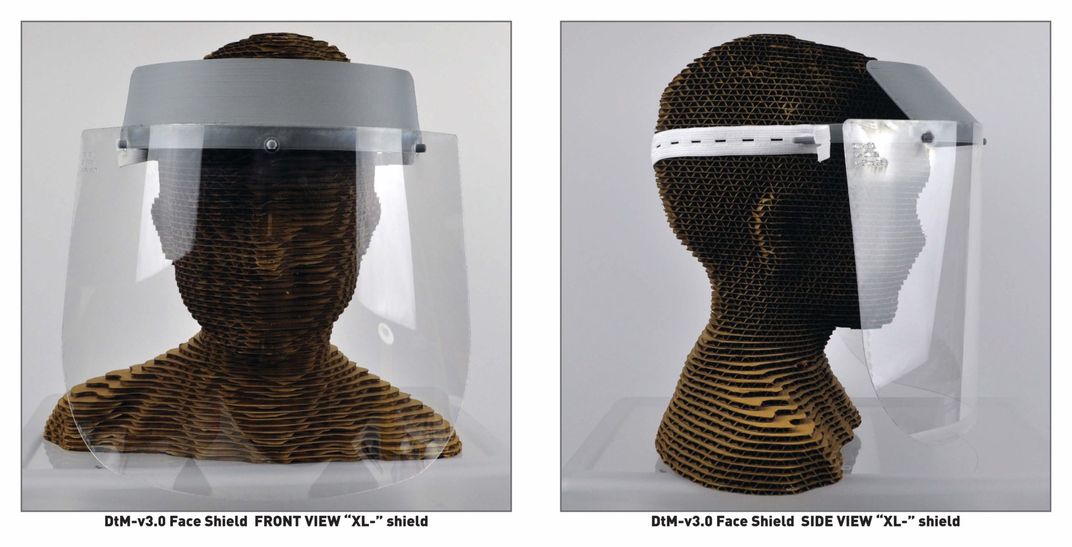

In response to the COVID-19 crisis, DtM released an open source 3D-printable face shield that anyone can download and print from the National Institutes of Health website.

How did you design and iterate your 3D-printable face shield?

Design that Matters (DtM) recruits students and professional volunteers to design medical devices for global health in low-resource settings—specifically in developing countries. The speed of the coronavirus pandemic is turning all clinical settings into low-resource settings. In response, we have shifted to applying DtM’s expertise in rapid prototyping, human-centered design and medical devices to the domestic shortage of critical health supplies.

Our COVID-19 Solutions project is a 3D-printable face shield PPE (personal protective equipment) for frontline health care workers. We took the Prusa Printer RC2 design as a starting point. Our initial design research with clinicians at MGH in Boston and the University of Washington Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, and a review of CDC requirements for personal protection equipment (PPE), revealed the need for improved protection for the wearer from aerosol and splatter from above, and improved washability and re-use.

Given the urgent demand for this design, how did you quickly conduct clinical testing?

According to representatives from the Washington State Department of Health, there is an urgent need for 500,000 face shields in this state alone.

On Friday, March 20, I brought a 3D-printed Prusa RC2 face shield to the University of Washington Medical Center for the first design review. Over the weekend, we assembled a team of over forty experts in design, engineering and medicine with volunteers from Spark Health Design, Microsoft, and Boeing, and clinical experts from Mass General Brigham, the University of Washington Harborview Medical Center and the UW Medical Center at University campus. Working nonstop in groups spread across the country, we blasted through three very fast cycles of prototyping and clinical testing.

The clinical test included a three-day pilot of the 3D-printed face shields at the Harborview emergency department, led by Dr. Graham Nichol, along with a rigorous clinical effectiveness and materials safety review by Dr. Dmitry Levin at the University of Washington. The final design was also evaluated and recommended for use by the NIH.

By Friday, March 27, we had posted the final face shield, DtM-v3.0, along with instructions for fabrication and assembly, on the NIH website.

What feedback have you received from frontline medical workers who have worn your face shield?

The response from clinical evaluators has been encouraging.

One ER nurse on the front lines at a Seattle-area hospital, wearing the DtM-v3.0 face shield for the first time a couple weeks ago, said: “I love it. It makes me feel safer. I was swabbing someone for a COVID-19 test when he vomited on me. It kept me clean.”

A nurse-practitioner on Twitter wrote, “I feel more confident that I can stay healthy and continue to take care of my patients and family. Plus, it is the most comfortable face shield that I have worn.”

Do you know how many times your mask has been downloaded or printed from the website of the U.S. Department of health and human services?

I don’t have a number for total downloads, but it was enough to crash the NIH website! We had to scramble early the week of March 30 with the NIH team to put up another post after the original post stopped loading.

We released the design using the CC0 public domain license, and we posted mirrors on PrusaPrinters and Thingiverse. We’ve since seen more than a dozen “remixes,” clever people refining the design for shorter print times or so that it will fit on the bed of smaller 3D printers.

We’ve heard dozens of groups printing this face shield around the country. We even heard from a team in Haiti printing our design in Port-au-Prince, and another group is adapting the design for production at scale in Kenya for use in Africa.

threeASFOUR

The wildly innovative National Design Award-winning fashion brand threeASFOUR was founded in New York City in 2005 by Gabriel Asfour, Angela Donhauser, and Adi Gil, who hail from Lebanon, Tajikistan, and Israel, respectively.

In response to the COVID-19 crisis, threeASFOUR began selling fabric masks for civilians, using 10% of the proceeds to donate medical masks to frontline healthcare workers.

Why did you decide to use prints from your 2012 collection “inSALAAM inSHALOM” to create one-of-a-kind fabric masks?

We felt that this pandemic had done something new to the world. For the first time in our recorded human history, the virus has united all nations, cultures, religions, races, skin tones, and social classes under one umbrella. Our inSALAAM inSHALOM project united both Jewish and Arabic cultures through celebrating the textiles of these two conflicted worlds by mixing the geometric patterns of BOTH and combining them as ONE.

The one-of-a-kind masks are due to shortage of fabric. We are recycling all the inSALAAM inSHALOM leftover fabric, so each mask is cut differently.

Who sews your masks, and where?

Since our factories are all shut down and all our team is “at home,” we were very lucky that our tailor friend, Marc, was open and excited to use his atelier in DUMBO, Brooklyn to cut and sew the masks.

You are using 10% of proceeds from the sale of threeasfour masks to purchase medical masks for frontline healthcare workers.

How many medical masks have you been able to donate through this initiative?

Yes, with that percentage of sales we have been producing “medical masks” with one of our U.S. factories, Onpoint Manufacturing in Alabama.

So far, because of the increased demand for threeASFOUR masks, we are able to produce about 300 “medical masks,” which are made from a high-tech lightweight and breathable bacterial protective silver-infused jersey.

Those are being donated (step-by-step as we produce them) to the medical workers in hospitals in and around New York City.

Now that the masks made from “inSALAAM inSHALOM” fabrics are sold out, will you continue this initiative? If so, how?

Yes, indeed, at the end of this week we will be running out of the inSALAAM inSHALOM fabric leftovers.

We are planning to continue the masks by recycling our 2016 fabrics and project “Quantum Vibrations,” which is based on sound vibration geometries. We feel it is very appropriate since these geometric symbols are commonly found in textiles of varied cultures and races around the world.

Open Style Lab

Open Style Lab (OSL), the inaugural recipient of the National Design Award for Emerging Designer, is an organization dedicated to creating functional wearable solutions for people of all abilities without compromising on style. Open Style Lab is providing tools for people to sew reusable fabric masks at home.

What is the OSL hackability toolkit?

With the goal to make hacking an empowering design skill for all people, The OSL HackAbility Toolkit is a set of physical tools for people with disabilities to redesign and hack existing clothing. The tools allow the process of sewing and making to be accessible for people with disabilities. It was co-designed with a group of teen girls from NYU IWD during the 2019 OSL Summer Program.

You launched your instructions for creating masks with an article in The Washington Post. What was the response from the paper’s readership?

Placing any design work out to the public is always met with a plethora of opinions and criticisms. This demonstrates the process of design is never complete, but can be accomplished to the best of one’s ability. Given the timely matter of masks, the paper’s readership had a large number of responses with a majority of those responses being positive.

You created a special version of your mask for healthcare workers. How is this mask different from your mask design for civilians?

The vinyl mask cover was not specifically a version for healthcare workers, but rather for anyone needing an extra layer of protection. The special version is a vinyl mask cover that used the same design specs as our fabric version. The mask cover was created to accommodate the following: (1) the use of plastic (vinyl) as a cover to be an alternative in prolonging the use of a fabric mask; and (2) the size of the mask to accommodate the most commonly used masks such as the delta and N95.

Will you continue to iterate your mask design?

Yes, we would like to iterate based on feedback from the community. For example, a practitioner reached out who wanted to use our mask cover design for the sign language interpreting community. They believed the design option our face mask design would allow better access to facial cues. We hope to find more requests like these and iterate our designs for more disability communities.