COOPER HEWITT, SMITHSONIAN DESIGN MUSEUM

Discover Smithsonian Open Access with 5 Design Treasures

This year, the Smithsonian Institution launched its Open Access initiative. Smithsonian Open Access invites you to share, remix, and reuse millions of the Smithsonian’s images—right now, without asking. Discover Smithsonian Open Access with these five designs drawn from the Cooper Hewitt collection. What will you create?

This year, the Smithsonian Institution launched its Open Access initiative. Smithsonian Open Access invites you to share, remix, and reuse millions of the Smithsonian’s images—right now, without asking.

Discover Smithsonian Open Access with these five designs drawn from the Cooper Hewitt collection. What will you create?

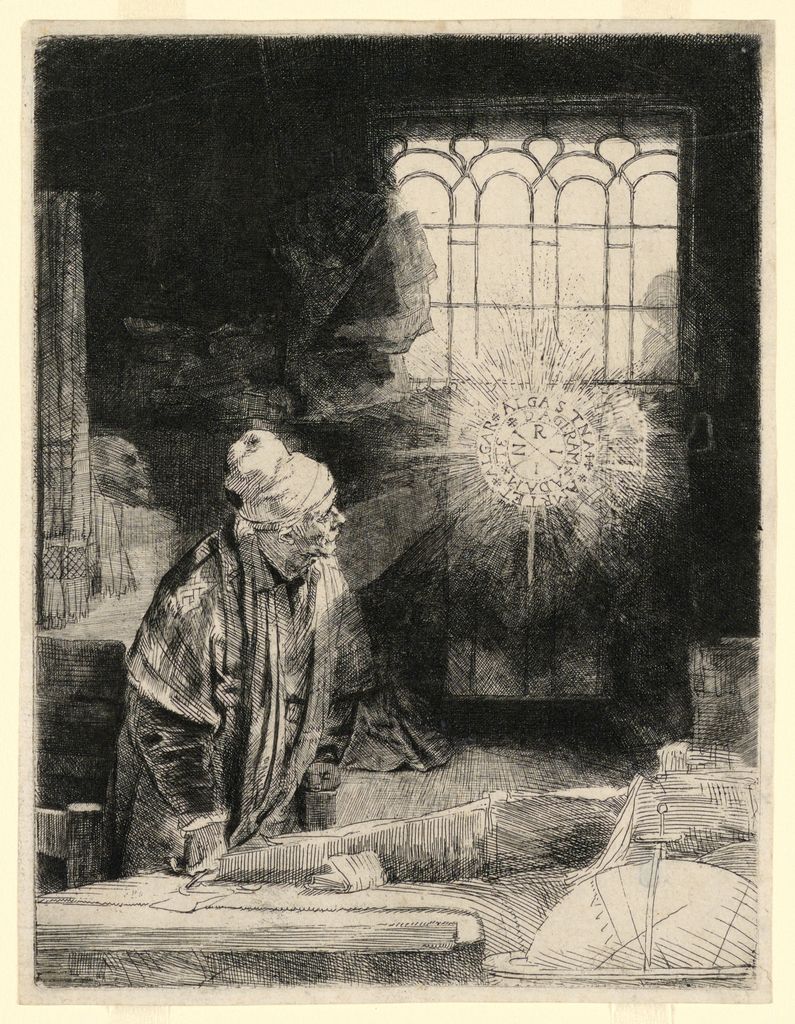

In a famous German story, a dissatisfied scholar named Faust exchanges his soul for limitless knowledge and pleasure. The tale of Faust’s deal with the Devil has captured the imagination of writers, filmmakers, and composers for centuries, spawning countless adaptations and retellings. This etching was created by the Dutch master Rembrandt around 1652—just over a century after the death of Johann Georg Faust, the historic alchemist, astrologist, and magician said to have inspired the fictional Faust. Here, we see Faust in his study, spellbound by a fantastical and radiant magic disc.

Although demolished in 1968, the Imperial Hotel (1919-22) in Tokyo designed by Frank Lloyd Wright remains his best-known work in all of Asia. Wanting to unify every aspect of the building, he designed its exterior as well as interior. This chair was one of many that filled the hotel’s extravagantly decorated banquet hall called the Peacock Room. Its shaped backrest and colored leather upholstery echoed the hall’s geometric motifs and stylized wall paintings.

Gotham, anyone? In 1916, concerns that towering skyscrapers would block light from reaching the streets below prompted New York City to pass the nation’s first citywide zoning code. The result, colloquially known as the “set-back law,” produced the iconic stepped silhouettes of structures like the Waldorf Astoria and the Empire State Building.

This drawing, one of a series of four by architect and illustrator Hugh Ferriss, was originally published in the New York Times in 1922. Later republished in Ferriss’ 1929 book The Metropolis of Tomorrow, these drawings not only influenced architects and urban planners, but also comic book artists and filmmakers striving to envision futuristic cities.

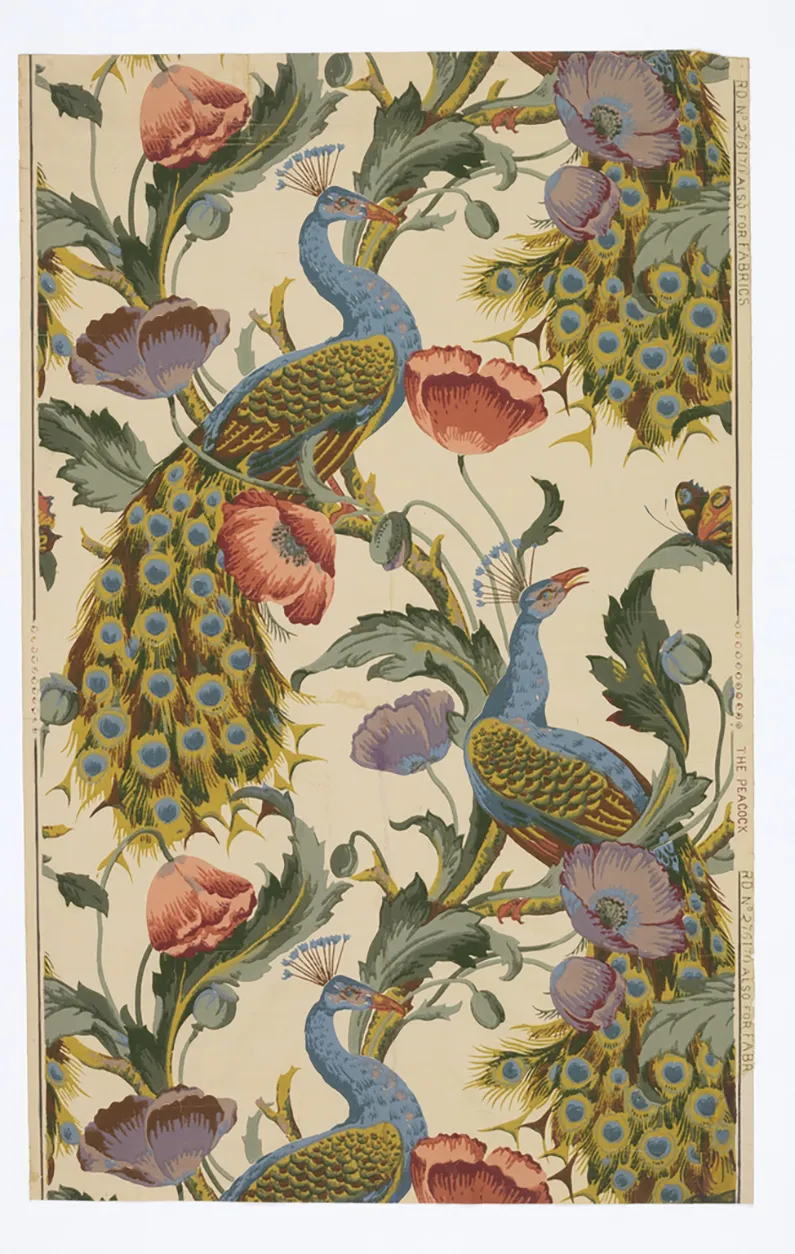

Popularized by Oscar Wilde and the Aesthetic movement, peacocks grace more than 50 wallpaper designs found in the Cooper Hewitt collection. In this example, eye-catching peafowls fan their plumage amidst pink and purple poppies, conjuring visions of formal landscaped gardens.

This dragon robe (ji fu吉服, literally, auspicious dress) is part of a long tradition. Dragon robes originated in the Liao dynasty (907-1125), and continued to be donned during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). The wearer’s status and gender determined the color of the robes, the number and placement of robe slits, and other elements of the garment.

This robe likely belonged to an official during the Qing dynasty’s Jiaqing (嘉慶) period, which lasted from approximately 1796-1820. This is suggested by the robe’s brown color, its two front and back slits, and the motif of the five-clawed dragon. Theoretically restricted to emperors and princes, five-clawed dragons circulated more widely during this period of the Qing dynasty. A closer look at this robe reveals more auspicious details, such as a peony, a flaming pearl, a lotus, and a fish.