The Migratory Adventures Of The Enigmatic Long-Tailed Jaeger Will Soon Be Revealed

:focal(2619x1391:2620x1392)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Mary_Lewandowski-National_Park_Service2.jpg)

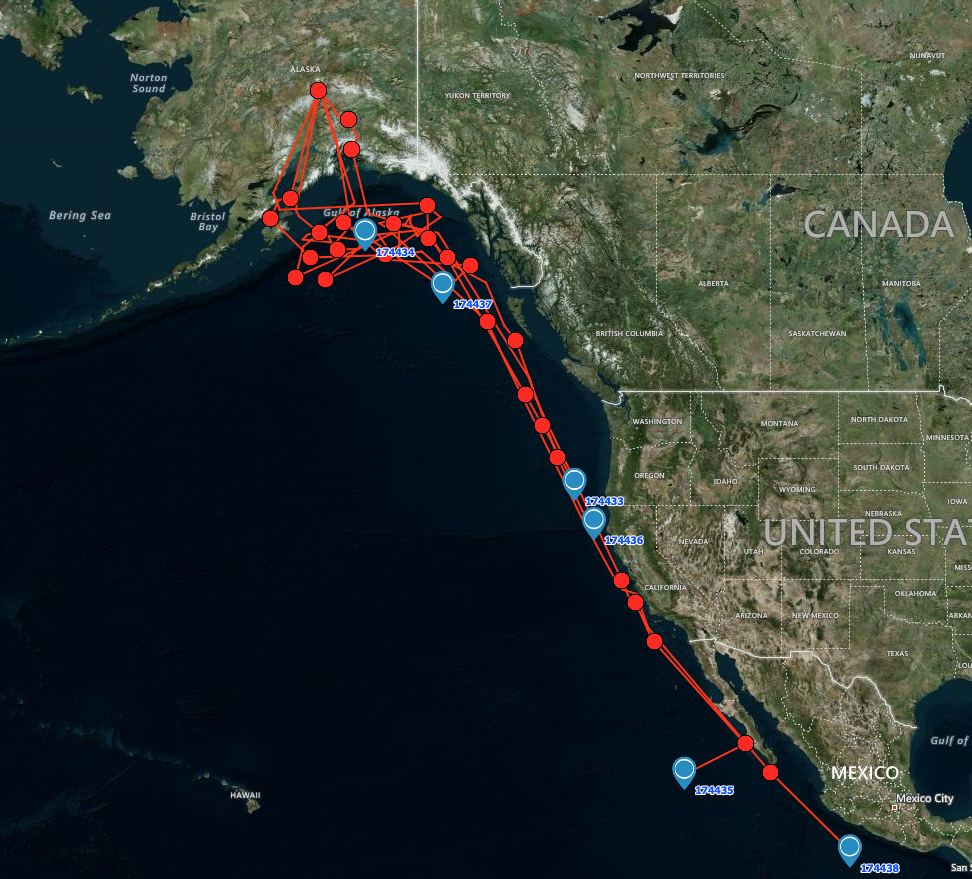

The mysterious whereabouts of the Long-tailed Jaeger are about to be unveiled. Last June, research ecologist of the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center (SMBC), Dr. Autumn-Lynn Harrison hiked up mountains in Denali National Park and Preserve in Alaska to track down this elusive seabird that spends most of its life out at sea, but uses the alpine tundra —a high elevation habitat— to breed in the summer.

Knowing that Jaegers are easiest to catch while incubating their eggs, Harrison, who is also the Program Manager of the SMBC Migratory Connectivity Project, went in search of their nesting sites.

She found them —after a few failed leads— with the help of Denali National Park ecologists Laura Phillips and Emily Williams. Six individuals are now being monitored via solar-powered satellite tracking devices that sit low on their back: a technological marvel that represents only about 2% of their body weight.

Harrison is no stranger to Long-tailed Jaegers. Last year, she tracked the first recorded migration path of the species in the Pacific Ocean, from a breeding population near Nome, Alaska, where the tundra is at sea level. On Alaska’s Arctic coastline, she also is tracking a pair from low elevation tundra along the Beaufort Sea, to compare the migration routes and wintering areas of the different populations. But in many parts of the world, including Denali in Alaska’s interior, they prefer higher, drier tundra. Their remote nesting habitats, combined with their long periods out at sea, makes them a particularly difficult species to study.

This research mostly aims to track the movements of Long-tailed Jaegers within Denali National Park, and through their migration to the Pacific Ocean. Understanding migratory connectivity is indispensable for the protection of species and essential to the Smithsonian Conservation Commons goals. Through its Movement of Life action area, the Commons develops the science to conserve and manage migration as a critical process for maintaining biodiversity and healthy ecosystems. It also helps integrate full-life cycle biology into the conservation plans of governmental and non-governmental partners.

Harrison believes it is a particularly critical time to document the connections of this seabird’s migrations to and from Denali National Park, as the environment that they use for breeding is changing. Some evidence shows that locations where Jaegers used to reproduce no longer support the species.

This study is also part of the park’s Critical Connections Program, which is focused on tracking and studying migratory birds that spend their summers in Denali. By expanding knowledge about the year-round needs of migratory wildlife of Alaska’s national parklands, this project and others will provide critical information to park managers for implementing long-term management and conservation strategies.

In the past few weeks, the tagged Long-tailed Jaegers started their migration towards the Pacific Ocean. Soon we’ll find out where these seabirds spend most of the year.

The Conservation Commons is an action network within the Smithsonian Institution (SI), highlighting the relevance of science and innovative interdisciplinary approaches across science and culture to on-the-ground conservation worldwide.