In Six Years, Movebank Has Collected One Billion Animal Locations

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Kinkajou_tagging_in_Panama_Credit_Untamed_Science_Roland.jpg)

In recent years, big data has become a popular term and a valuable asset. If managed and analyzed correctly, large amounts of scientific data can lead us to more precise answers to the most pressing issues of our time.

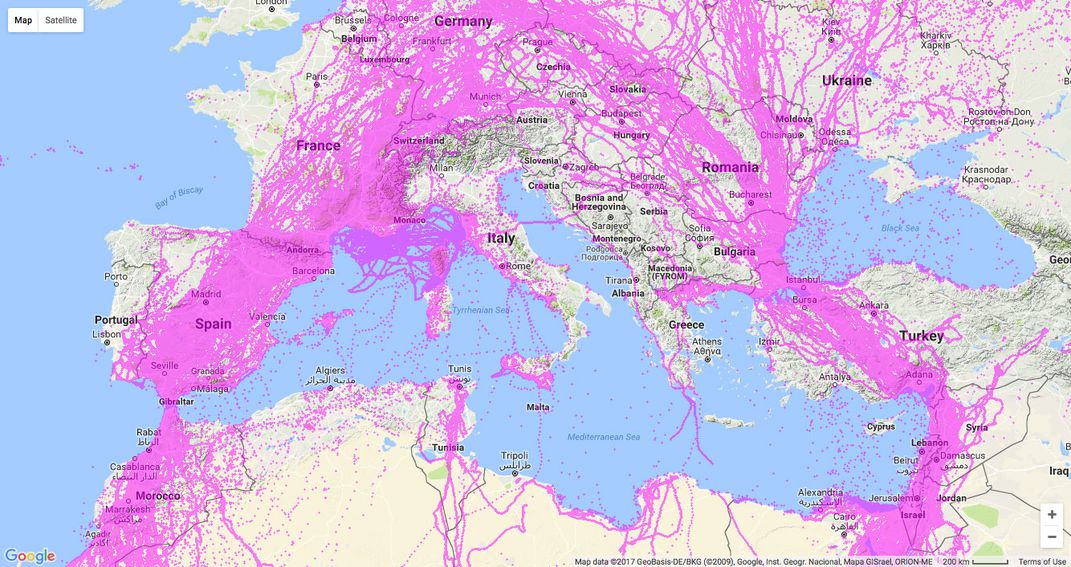

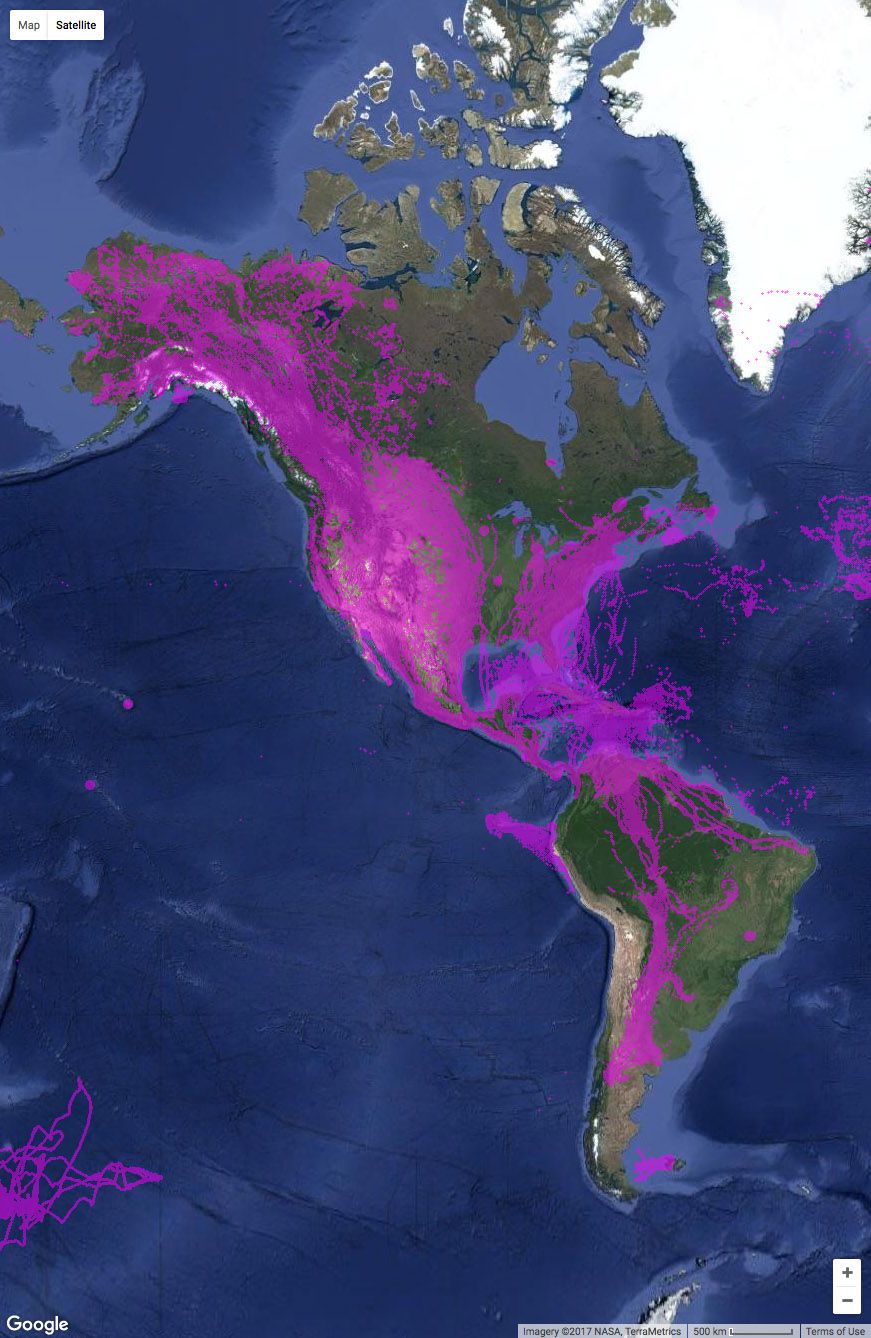

Movebank is big data, collected directly from wild animals. By September 2018, this global animal tracking database will have stored one billion animal locations. Since its launch in 2012, it has grown exponentially. New scientists are constantly joining and taking advantage of the online tool to store, organize, analyze and share their research data. And it will continue to expand even faster, to keep pace with the rapid evolution of the movement ecology field.

The idea to create a database was conceived by scientists Roland Kays, from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and NC State University, and Martin Wikelski, from the Max Plank Institute for Ornithology. They were working together at the Smithsonian Tropical Research institute (STRI) in Panama, where they had created an automated tracking system for animals on Barro Colorado Island. The large amounts of data generated made it impossible to keep up with only a notebook.

“As we built the database and got it up and running, we thought: there are probably many other scientists who would like to have these tools,” said Kays. “So we made it a community resource.”

As such, it promotes collaboration. Recently, over 100 scientists providing data on hundreds of mammals, analyzed the effects of human disturbance on animal movement. Their results were published in Science this year.

Kays, who is a Research Associate at STRI, loves to emphasize how Movebank gives data the opportunity for a second life. After it is used by the original researchers, it can go on to answer new questions and serve other purposes: National Geographic uses Movebank data to tell the stories of animals, and school kids use it for science projects.

Understanding animal migration enhances conservation efforts too, which is essential to the Smithsonian Conservation Commons goals through the Movement of Life action area. If a species population declines, knowing their migration route allows scientists to explore potential dangers along its path. For example, scientists working with white storks found areas where people are hunting them and are now trying to address the problem.

This kind of knowledge will scale up even more through a novel initiative: ICARUS (International Cooperation for animal Research Using Space), as an international team of scientists led by Wikelski and including Kays— work with a new antenna on the International Space Station. Depending on how the testing phase goes, the technology may be available to scientists soon, allowing them to use smaller tags to track a larger variety of species.

Just like the animals it follows, Movebank is very much alive. As the tracking hardware, software and analytical tools continue to develop quickly, movement science will advance accordingly. In the meantime, Kays hopes to see even more researchers join its ranks.

The Conservation Commons is an action network within the Smithsonian Institution (SI), highlighting the relevance of science and innovative interdisciplinary approaches across science and culture to on-the-ground conservation worldwide.