#BlackBirdersWeek: Celebrating and Encouraging Diversity in Conservation

The first #BlackBirdersWeek celebrates Black birders and nature enthusiasts while inspiring more conservation-curious to join their community.

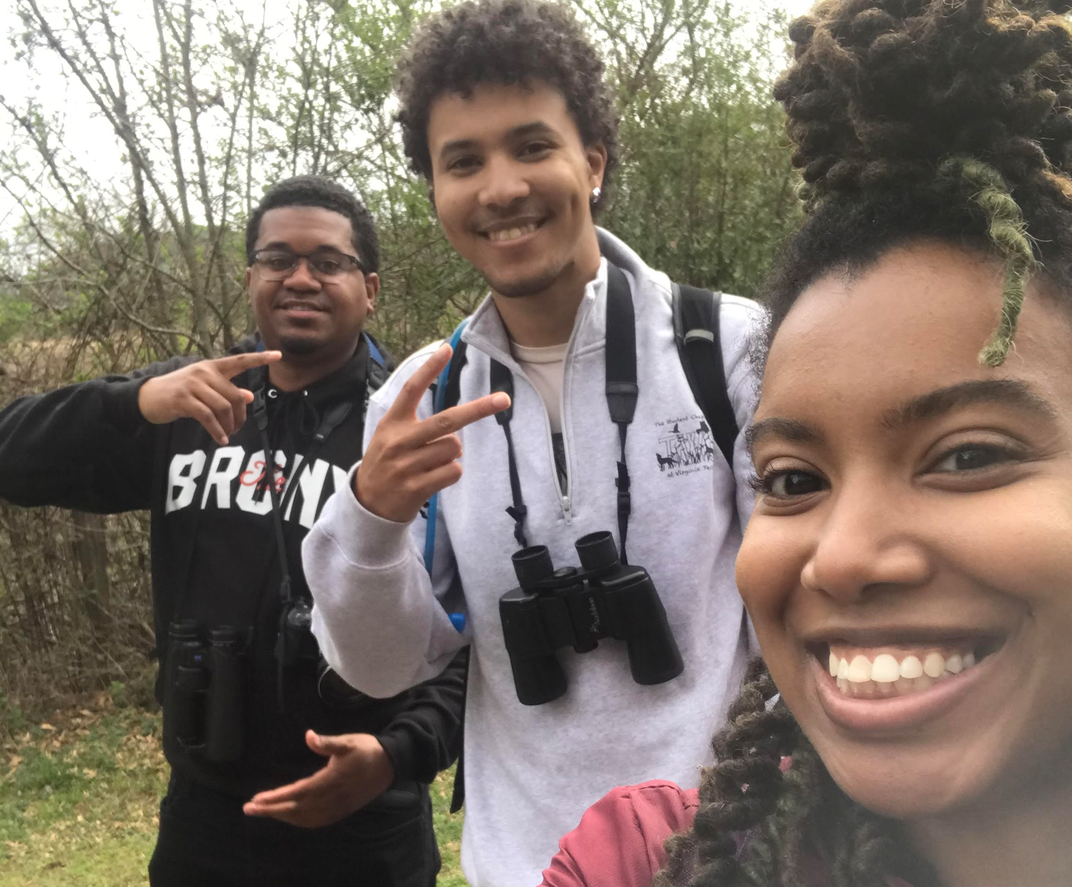

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/IMG-7803_-_Copy.JPG)

At Earth Optimism, we try to curate good news in conservation to spark hope and action. But while we are in the midst of such atrocious social and environmental injustices and a public health crisis – optimism is incredibly difficult to find. Fortunately, a group of passionate Black birders in the nature-enthusiasts community have found an inspiring way of turning heavy emotions into a weeklong event to encourage visibility and growth in this field. We had the honor of listening to stories from organizers: Ashley Gary, Sheridan Alford, Chelsea Connor, and Joseph Saunders, and learning not only how this particular movement was sparked but how all of us in conservation can do our part to promote and foster inclusivity.

Can you tell us your personal story of how you got into birding?

Ashley Gary: The first time I realized that I really liked birds was after watching Sir David Attenborough’s Life of Birds. There was such a variety of adaptations that I was truly in awe. The fact that they have made a home for themselves on every continent was so impressive and that’s not even touching on their diversity of colors and shapes and calls and so much more. I didn’t officially start birding until recently. In 2019 I went birding for the first time with Jason Ward and Tyus Williams and it was just so much fun. There is something special about being out in nature with friends, admiring the surroundings and wildlife, and just enjoying yourselves. Since then I always look and listen for birds when I take nature walks and use apps like Merlin ID to try to identify what I see out in the field.

Sheridan Alford: I've always had a fascination for birds but that didn't manifest into birding until I was invited on my first bird walk by a colleague of mine. She was a big supporter of connecting Black naturalists and told me that the walk would be led by Jeffrey and Jason Ward, who I had to google at the time. I was so glad that I did, I was almost star-struck when meeting them and realizing these are two Black men that bird and are THRIVING. Seeing someone I could identify with birding is what really propelled my confidence that THIS is what I wanted to do.

Chelsea Connor: I'm from Dominica (it's a beautiful island in the Lesser Antilles), and its nickname is The Nature Island because of all of the untouched forest on the majority of the land. I have three distinct bird memories that really fostered my love for birding. The first being the nostalgia from the sound of tiny fluttering wings of the small flock of bananaquits my grandmother would feed sugar at her house when I was growing up. They're called sugarbirds on some islands for a reason and I had so many questions about how birds "worked". I could watch them forever. The second involves one of the endemic species of parrot on my island. My first time seeing the mated pair of Sisserou parrot (or Amazona imperialis) that used to live at the Botanical Gardens left me awestruck. And lastly, going down Indian River on my uncle’s boat, seeing yellow warblers flit through dappled sunlight, calling occasionally. Birds are little bits of wonder and magic. I wanted to keep catching those moments.

Joseph Saunders: Not unlike my peers in BlackAFInSTEM, my interests in naturalism began at a very early age. Unlike the dedicated birders, mine was founded as a herper and later expanded to entomology. I really have to credit my new family in BlackAFInSTEM for the push to include a love of birds. I am a professional wildlife photographer (@reelsonwheels: Instagram) and I hadn't photographed birds until becoming immersed with this amazing group of Black scientists and naturalists.

What challenges did you face entering this field, and what recommendations would you give someone else who might encounter the same obstacles?

Gary: The biggest challenge for me was just never having that sense of community. As I was growing up I didn’t know anyone else who loved nature and wildlife in the way that I do and that was always something that I had to cherish alone. For me personally, I love to be able to share my passions and I had less desire to be out alone, especially because there are issues of safety being at parks and in more remote areas by yourself. I encourage people to take advantage of social media and apps like MeetUp to find others who have your same interests. It is easier than ever to find and connect with people. If you’re a Black birder, please scroll through the #BlackBirdersWeek hashtag on Twitter and Instagram, you may be able to find fellow nature lovers in your area.

Alford: Getting an education in the south and within the same realm as hunting, forestry, and natural resources, I often felt that I needed to constantly prove my knowledge and worth in a space that was dominated by white males. It was important for me to understand that I am enough and I do belong in the same room and being offered the same opportunities. Learning to be confident in your abilities is the key to becoming comfortable in necessary spaces, people will be drawn to the light that you exude!

Connor: Since I've moved to Texas I've been nervous about going out with a pair of binoculars. Even though I am looking at birds, I'm not sure if everyone would see it that way. The racial history in America is palpable and constant and I don't the privilege to pretend it doesn't happen. Another issue is having your IDs second-guessed, like when you identify a bird or mention that it occurs here (because you've seen it and records of it!) and being told that that's not true because they haven't seen it for themselves!

Saunders: The challenges I faced are probably different from my peers. I have been a permanently disabled paraplegic since birth. Many of my challenges surround mobility and accessibility to wild spaces. Ironically, using a wheelchair full-time presents to most people the idea I am not as powerful (or threatening per the imagination of racist people) as able-bodied Black men. Typically, I am left alone, or even asked if I need help rather than threatened. This however does not apply when I am driving. I have been chased by locals out of rural towns while seeking birds, reptiles, or beautiful landscapes to photograph. In fact, this happened most recently in April, and it was my BlackAFInSTEM family who cared for me, and supported me in the aftermath of that traumatic experience. I may not have had the chance to photograph April's full moon, the largest of 2020 if not for them. They gave me the courage to keep searching after an event I thought might be my last as a Black naturalist. I was honestly fearful for my life in those moments.

How did the idea for #BlackBirdersWeek come about? Did you expect it to get as much traction as it has?

Gary: #BlackBirdersWeek was the brainchild of Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman. She pitched the idea to the BlackAFinSTEM group after the racist incident in Central Park involving Christian Cooper as the intended victim. Unfortunately, many of us had shared experiences of racism experienced while being Black outdoors. We wanted to amplify Black birders and Black outdoors folks to say that we’re here and we want our experiences to be acknowledged by our non-Black counterparts. Fellow members agreed and members mobilized to create this week very rapidly.

I expected this week to do very well on Twitter because, in my experience, Twitter has been very welcoming and supportive. However, I must say it has been amazing to see this progress to something so large with members of the BlackAFinSTEM group being able to have their voices heard in a wide variety of forms and on so many outlets. I am very proud to be in a group with so many intelligent, caring and ambitious Black people who strive to make a difference in the lives of others by shining a light on Black experiences and making room for conversation in the birding community while promoting diversity.

Alford: After the incident involving Christian Cooper surfaced on the internet, a lot of the members in the group identified with the pressures of being Black and carrying out our field tasks in a world that marginalizes minorities. We wanted to create a positive initiative that would 1) draw visibility and representation to uplift and recognize Black birders and naturalists in their respective professions, 2) create a necessary dialogue within the birding community to facilitate a comfortable environment for all, and 3) promoting the importance of diversity in these public spaces.

We knew we had a good idea but this reception from others has been astounding! Seeing all the allies and people posting with the hashtags has brought tears to my eyes. I love that people are feeling comfortable enough to share their stories with us.

Connor: The idea was pitched by Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman and a group of us and her just really went ahead and put events together. All of the members had input also for the details and content we put out and help for direction. Even our statements, there's a piece of each of us in every one of those.

We definitely didn't expect that there would be this level of response. We knew that it would resonate and people would respond, but to see how it has grown is just... We are awestruck.

Saunders: The idea of Black Birders Week came from Anna Gifty Opoku-Ageyman, which is sort of funny as her academic and career track is economics. She is sort of our odd-duck in a room full of naturalists, and we wouldn't change a thing about it. She arrived at the idea after the group had many conversations sharing our frustrations, anger, and fear about the assault on Christian Cooper in Central Park while comforting one another through it. Initially, I was not sure what to expect from it as this was new grounds for me. Very quickly everyone began to participate with generating ideas for the event, afterward people began taking action. It was at this point I knew we had something special. It was evident we all were willing to devote ourselves to the success of Black Birders Week.

Conservation tends to be a historically, predominantly white field. What can do we do to support diversity in this conservation?

Gary: If you want to draw in a diversity of people, you really have to make outreach efforts that support underrepresented communities. It can change someone’s life to see another person who looks like them in a career. It crystallizes the possibility that this could be something they can also do. It is also important to check the biases within your institutions. The culture of many organizations does not make it pleasant for Black people or other people of color to be in that space. No one wants to feel ignored or alienated. Systemic barriers are in place that discourage more diversity and they have to be dismantled if you want progress and change.

Alford: I think the biggest thing that helps promote diversity is providing resources for disenfranchised groups to participate. Representation is key, but children in inner cities or high school students looking at programs for college never see the images that were meant for them due to lack of presence. There is a lot of infrastructure already in place in schools and nonprofits that would greatly benefit organizers and shed a positive light on the supporters that is also vitally important.

Connor: Supporting diversity is more than just opening hiring or saying you want to have more BIPOC in a space, you need to also work to make sure that they are heard and that they feel safe. Its not enough to just put there, what are you doing to make sure that once they are in they want to stay? That they are not facing discrimination on the inside? Are you making sure they get to do the same opportunities? Are you actively fighting racism, even when it's not overt? If there's fieldwork to be done, what measures have you taken to ensure field safety in case they are approached? There are more questions in this vein and the answers need to be along the lines of, "Yes, we are being open and listening."

Saunders: To support diversity in conservation, related fields must first realize conservation is a global initiative, and globally, white people are a numerical minority. The prevention of global ecocide cannot succeed without Black, Brown, and Indigenous people. For domestic efforts, all institutions committed to conservation must adopt and enforce a zero-tolerance policy related to racial discrimination. The privileged opportunity to save the planet should not be granted to people of such poor character who see it fit to oppress other demographics. The consequence of allowing this to persist is a marginal turnout of people dedicated to this planet's most pressing problem. The survival of our species and that of countless others depends on us getting this correct. Additionally, it is not enough to continue to only promote initiatives of inclusion. Often, what this means is people from oppressed demographics are merely included in spaces that are not safe for them. We cannot perform our best work while also coping with constant microaggressions, or worse, explicit forms of discrimination. This is perhaps the greatest value of BlackAFInSTEM. Not only does this work promote conservation, but it does so in a safe, caring, and supportive environment we have created for ourselves. Opportunities like this should be made available for all institutions with conservation as their objective.

Are you optimistic about the future of nature and conservation becoming more inclusive?

Gary: I try to be optimistic that not only with nature and conservation will become inclusive, but also that society as a whole will evolve and begin to see that we are all people worthy of dignity, respect, love, and belonging. This is truly a possibility, but it requires hard work, hard truths, and being uncomfortable. Growth is never comfortable, but it is necessary.

Alford: I genuinely am. I've seen a tremendous step taken by supporters of #BlackBirdersWeek to highlight their Black colleagues and amplify the work that still needs to be done. I think the interest is there and all parties just need to continue to act on it.

Connor: Oh definitely! At first, I thought it was just like 15 people out here that looked like me. I saw them on Twitter and I followed them, but then that grew as I saw interactions and questions being asked and retweets. Now with #BlackBirdersWeek... Honestly from day 1, #BlackInNature, I was beside myself because I had never seen so many black people outside enjoying nature. A stereotype is that we don't like being outdoors and doing those things, and maybe sometimes we joke about it but that's not true. We love the outdoors and seeing the actual flood of pictures of Black people doing that, unapologetically taking up that space? I've been in tears on and off since we started.

Saunders: It is difficult to find optimism in the current climate of our country. I don't want our only option for inclusion to be an environment that does not value our talents and even seeks to undermine them or harm us. I want us to be afforded the opportunity to work in environments created with our best interest in mind, and not as an afterthought or corporate quota. After this experience of creating Black Birders Week, I have grown more confident we will show what work is required to create infrastructure for marginalized demographics to show their talents.

Follow #BlackBirdersWeek on Twitter and Instagram.

You can also follow the organizers here:

@BlackAFinSTEM

Sheridan Alford: Twitter, Instagram

Cheslea Cooper: Twitter, Instagram