Meet the Community-led Conservation Advocate Working to Protect Madagascar’s Coasts

Vatosoa Rakotondrazafy is a passionate advocate for conservation and sustainability along Madagascar’s coastline communities. After working on small-scale fisheries research supported by the United Nations Nippon Foundation, Rakotondrazafy joined the Madagascar Locally Managed Marine Area Network (MIHARI), an organization that aims to represent marginalized fishing populations and work with them to create locally managed marine areas (LMMAs). Through these LMMAs, local communities can manage and protect both their own fishery practices and biodiversity by combining their traditional knowledge with the support of conservation practitioners.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Vatosoa_meeting_with_MIHARI_community_members_-_Copyright_MIHARI.jpg)

Vatosoa Rakotondrazafy is a passionate advocate for conservation and sustainability along Madagascar’s coastline communities. After working on small-scale fisheries research supported by the United Nations Nippon Foundation, Rakotondrazafy joined the Madagascar Locally Managed Marine Area Network (MIHARI), an organization that aims to represent marginalized fishing populations and work with them to create locally managed marine areas (LMMAs). Through these LMMAs, local communities can manage and protect both their own fishery practices and biodiversity by combining their traditional knowledge with the support of conservation practitioners.

Her work with MIHARI earned her the prestigious Whitley Award in 2019, which helped to further fund actions to expand and support additional LMMAs. Currently the President of MIHARI’s Board of Trustees, Rakotondrazafy also works with INDRI, a think tank working to protect both the marine and terrestrial biodiversity of Madagascar.

Vatosoa was a recent panelist for the Maliasili Community-Led Conservation in Africa event during Earth Month 2021. Here she tells us more about her amazing work and what gives her optimism for the future.

What inspired you to start a career in conservation?

I’m from Madagascar and grew up there. Madagascar is a beautiful country off the East Coast of Africa. It’s the fourth largest island nation in the world, and has a population of about 26 million people of diverse cultures and ethnicities. It’s really beautiful and has incredibly diverse flora and fauna - some species are only found on Madagascar. I wanted to become a lawyer to fight for human rights, I wasn’t initially interested in conservation. But I wasn’t able to join the university to study law, so I ended up studying geography and oceanography. It wasn’t initially my first choice, but I ended up loving it. I studied the environment in general, eventually studied marine conservation, and was selected for the United Nations fellowship on strategy to improve Madagascar's fisheries. This is when I really fell in love with helping to manage my country’s marine resources and helping the coastal communities, and the value that small-scale fishers have in the country. I got recruited to coordinate MIHARI right after this research. My research conclusion was that we need to empower Madagascar’s small-scale fishers in the management of the country’s resources, and I ended up being recruited to work for those communities.

I didn’t end up being a lawyer, but I ended up being an advocate for the rights of small-scale fishers in Madagascar, and I couldn’t be happier.

What challenges do local communities face when advocating for themselves? How are you working to overcome these barriers?

One of the big challenges that local communities face is the lack of awareness of existing legislation that could help protect themselves and their rights. Many live in very remote and isolated areas, far from representatives of regional authorities and the national government. This makes it hard for their voices and demands to be heard.

At MIHARI, we promote Locally Managed Marine Areas (LMMAs) so that local fishing communities come together with the local government, and sometimes, members of the private sector and NGOs to create mechanisms to sustainably manage marine and coastal resources. This local management is important because grassroots communities have the best knowledge of their local environments. They are able to manage their own marine resources and use context-specific, socially acceptable solutions to address issues quickly.

Local conservation initiatives include the promotion of alternative livelihoods, temporary fish reserves, and mangrove reforestation and management. Communities enforce these bylaws through dina or local customary laws, sets of mutually agreed-upon rules that are promulgated by the Malagasy state and whose violation will lead to fines. Another issue that the communities face is that the process of promulgation of the dina into laws can be a long process. This means communities are not able to bring those who break dina to court and are then afraid of retaliation in enforcing their community initiatives.

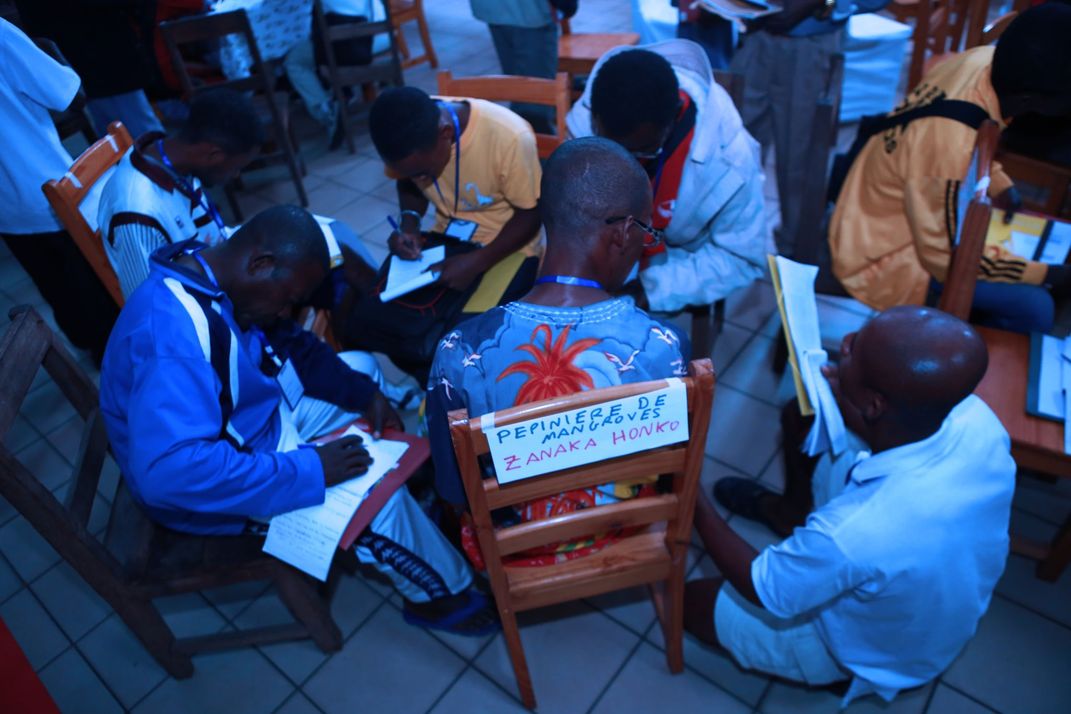

MIHARI connects more than 200 LMMA communities across Madagascar, through small-scale fisher gatherings, we facilitate networking and learning exchanges between LMMA associations. We also build local leadership and capacity building by providing training on public speaking, conflict resolution, evaluation, etc. Our forums bring together around 200 to 400 stakeholders, including coastal communities, NGOs, private sectors, government, and funders have proven to be catalytic in driving the most rapid growth in locally-led marine conservation seen to date anywhere in Africa and the broader Indian Ocean region. The 2017 national forum was a milestone for Madagascar’s fishing communities. It marked the first that fishing communities came together and presented three motions to the Government, NGOs and partners of the network.

As a result, in 2018, the Ministry of Fisheries made an engagement to create a reserved area for small-scale fisheries in order to resolve their conflict with industrial fisheries.

Tell us about using community-led conservation methods in your work.

The concept of LMMA (Locally Managed Marine Areas) in Madagascar was born in the southwest of the island in 2004 with communities coming together to manage community-led octopus closures. The initial seven-month closure of a distinct octopus fishing site allowed octopus stocks to recuperate and resulted in an increase in catch per unit effort (CPUE) for at least six weeks following the opening. The quick pay-off of this initial closure allowed fishers to see the immediate benefits of resource management interventions. LMMAs are areas of nearshore waters that are fully or largely managed by coastal communities, which are empowered to create and implement management rules.

LMMAs have seen a rapid expansion in Madagascar in response to declining productivity in traditional fisheries and as the benefits of community-based management become more evident. Madagascar now has 219 LMMAs covering 17,000 km2 of the country’s continental shelf.

The LMMA approach has 4 management models: creation of temporary and permanent fisheries closures, mangroves restoration, development of alternative livelihoods, and establishment of local regulation.

How is traditional knowledge helping to conserve Madagascar's coastline?

The small-scale fishers are the guardians of our seas, they have abundant traditional knowledge of best practices in the management of our coastal resources. They live from and for the ocean and they have on-the-ground experience so they are able to highly contribute to finding solutions for the management of marine resources.

Even if these communities did not receive a formal education, for me, they have a doctorate in ocean science and governance and years and years of generational knowledge of natural resources management. I am always amazed at how they know so well the ocean, how they can predict the weather to decide whether or not to go fishing and which direction they should sail. They know where fish stocks are and how to preserve the resources, all that without having complicated scientific tools or formal education. Their traditional knowledge combined with modern ocean science for example: inform national policies like temporary fishing closures in Madagascar. Local enforcement of community conservation efforts are enforced through dina or local traditional customary laws and guidelines that have governed these communities for generations and generations.

Can you share a success story from your organization?

Before, small-scale fishers were vulnerable, marginalized, and isolated. Since they joined MIHARI and the network was there to represent them, they now have a voice, they are now involved in high-level national decision making, they’re recognised for their traditional knowledge. The success of the three motions in 2017 was a big story for Madagascar, as the fishers didn’t have this kind of representation or voice before. Today, we have 219 LMMA associations within MIHARI, and more than 500,000 small-scale fishers in Madagascar.

Vatosoa also shared three conservation success stories from small-scale fishers supporting the locally-managed marine areas...

Bemitera from Analalava: "We were shy before. As we are in remote areas, some of us are afraid to go to town. Since we got leadership trainings and capacity building, we are more confident in public speaking, in negotiating for our rights with key people. Exchange visits we attended helped us also to better manage our LMMA as we were able to see best practices from other communities."

Richard from Tampolove: "We started seaweed farming in 2010 in 5 villages, and we produced 13 tons of seaweed per year at that time. Currently, seaweed farming has been extended to 3 other villages and we reached 400 tons of production last year."

Dassery Amode from Mananara: "We started to create an octopus reserve in 2013. Before that, we rarely catch octopus and almost all small size. Today in 3 months closures, they get more than 1 ton with big size around 7 kg."

We were humbled to have our work recognised on a global scale when we won the Whitley Award in 2019. I continue to be a huge advocate for small-scale fishers, they’re the future for guaranteeing Madagascar’s sustainable management of the country’s natural resources. They’re the guardians of the ocean so the prize was a recognition of their work too.

Can you tell us more about your new role with INDRI?

Since November 2020, I have joined a Malagasy think-tank called INDRI, which mobilizes the collective intelligence of all stakeholders nationally to restore Madagascar’s marine ecosystem and re-green the island. For terrestrial landscapes, I am leading an initiative called Alamino. Alamino is the Malagasy name of the Agora of Landscapes and Forests, an initiative launched by INDRI to mobilize collective brainpower to reverse forest loss and restore four million hectares of forest in Madagascar by 2030 as per the engagement of my country in the AFR 100 (the African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative). We bring together all key stakeholders: civil and military public authorities, NGOs, civil society, representatives of local communities, religious groups, the private sector, experts, and donor agencies, and facilitate collaboration with collective intelligence tools that are completely new to Madagascar.

For the seascape, we are planning soon to create the Blue Agora of Madagascar: an agile and powerful mechanism bringing together all marine stakeholders, including government, private sector, small-scale fishers, NGOs, experts, donor agencies. All experts in marine resources in Madagascar constantly express the need to move away from the silos in which each type of actor has locked itself. They stress the need to build a real shared vision and ensure the commitment of all stakeholders in the discussion and decision-making process. To date, there is no space in the country allowing these organizations to meet, exchange views, overcome their differences and contradictions and coordinate their action with a view to achieving sustainable management of the country's marine resources, such as the restoration of fisheries stocks, the development of new economic sectors such as aquaculture, access for traditional fishermen to marine resources and markets, etc.

What makes you optimistic about the future of our planet?

There is a mobilization of lots of people now joining hands to conserve nature - from young people to women and local communities and activists. We’re also now learning from each other as countries and regions more than before. This means that we can share best practices, we are more aware of the destruction of our environment and together, we are all working hard to find solutions.