Exploring the Social Side of Conservation

A case study demonstrates how incorporating social science into conservation actions can produce more effective, equitable, and lasting change.

What comes to mind when you think about nature? Many people imagine untouched wilderness – verdant old-growth forests, flowery meadows buzzing with life, or pristine beaches with sparkling waves.

The reality is that most of the world has been impacted by humans in some way. Over half of our planet’s surface can be classified as shared or “working” landscapes and seascapes – mosaics of natural ecosystems and human activities. From above, you might see a typical landscape as a patchwork of towns, farms, roads, and factories surrounded by forests, fields, or mountains. Take a flight over a coastal area instead and you may see cities, ships, energy plants, and bustling public beaches contrasting against the vast blue ocean.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Communities can learn to live in harmony with their local environment, thriving on the resources it provides without jeopardizing the ecosystem services that make it all possible. With the climate changing and biodiversity declining, we urgently need to understand how human activities influence the world around us. Considering the deep connections between people and planet, protecting nature is often also a matter of protecting ourselves.

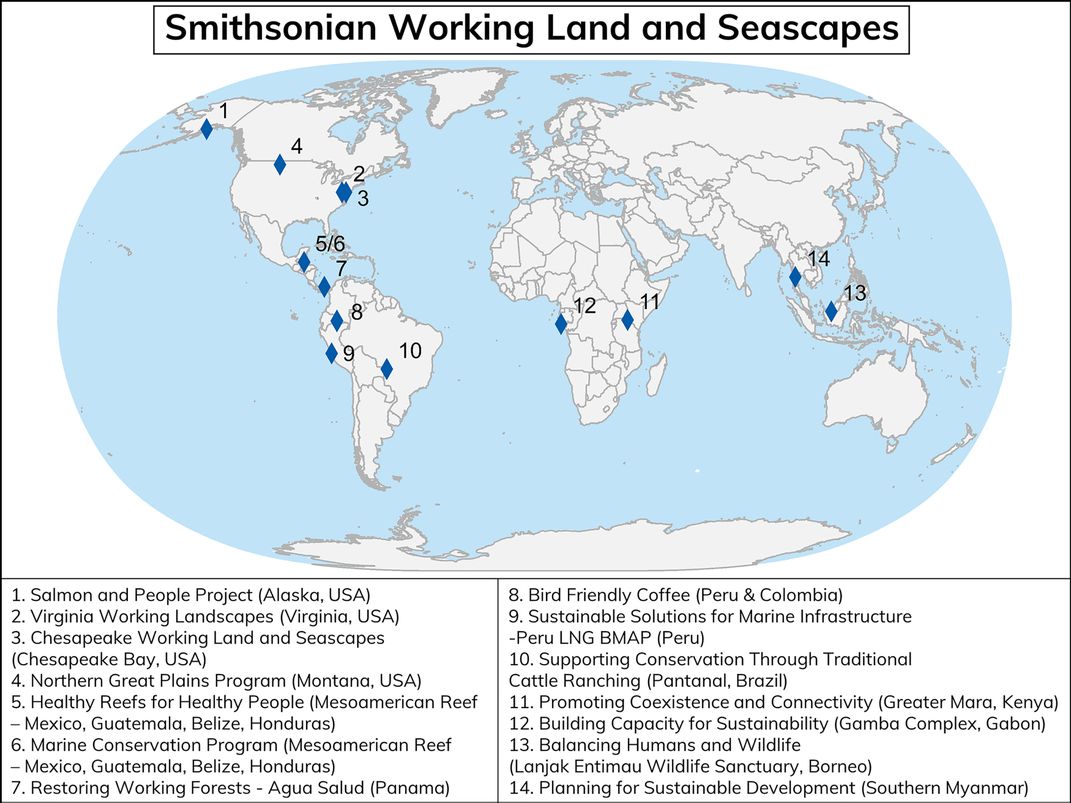

A recent publication in Frontiers in Conservation Science calls on conservation initiatives to shift their focus away from the few remaining unpopulated areas, towards the shared spaces where humans live and work alongside nature. In doing so, conservation has the potential to create solutions to multiple problems. This case study – the first of its kind – uses the Smithsonian Working Land and Seascapes Initiative (WLS) to explore how incorporating social science into conservation actions can produce more effective, equitable, and lasting change.

“The application of robust social science methods for conservation in working land and seascapes is absolutely critical for conservation success,” explains James McNamara, a Conservation Research Consultant who works with the Smithsonian Gabon Biodiversity Program (GBP). “This paper breaks new ground by identifying a set of specific topics and questions to help conservation practitioners develop more integrative and holistic programs to account for the human dimensions of conservation.”

Designing a conservation strategy that accounts for so many different elements can be difficult, especially at the scale of an entire landscape or seascape. Environmental problems tend to be fueled by a mix of social, economic, and political factors – a blend as unique to each place as the local ecosystem.

Untangling this complex web of causes and consequences is what social scientists do best. Social science can provide insight into the human dimensions of a situation, like how people’s knowledge, values, and behaviors affect – or are affected by – a conservation decision. Together, natural and social science can paint a more comprehensive picture of a landscape or seascape.

“The paper brings a very nice overview about the different aspects of social sciences in working landscapes, based on evidence from several places around the planet,” says Rafael Chiaravalloti, a Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute research associate. “The paper can be used as guideline for those aiming to better understand places where the interaction between people and nature is key.”

Those places include 14 WLS project sites, where interviews were conducted with representatives to learn more about their project’s background, objectives, activities, outcomes, and connections with human dimensions. The findings revealed 38 topics and questions from various disciplines of social science that could be explored, yielding either place-based or theoretical insights. Place-based solutions can help advance similar efforts in similar contexts, while theoretical concepts can have wide-ranging, generalizable implications.

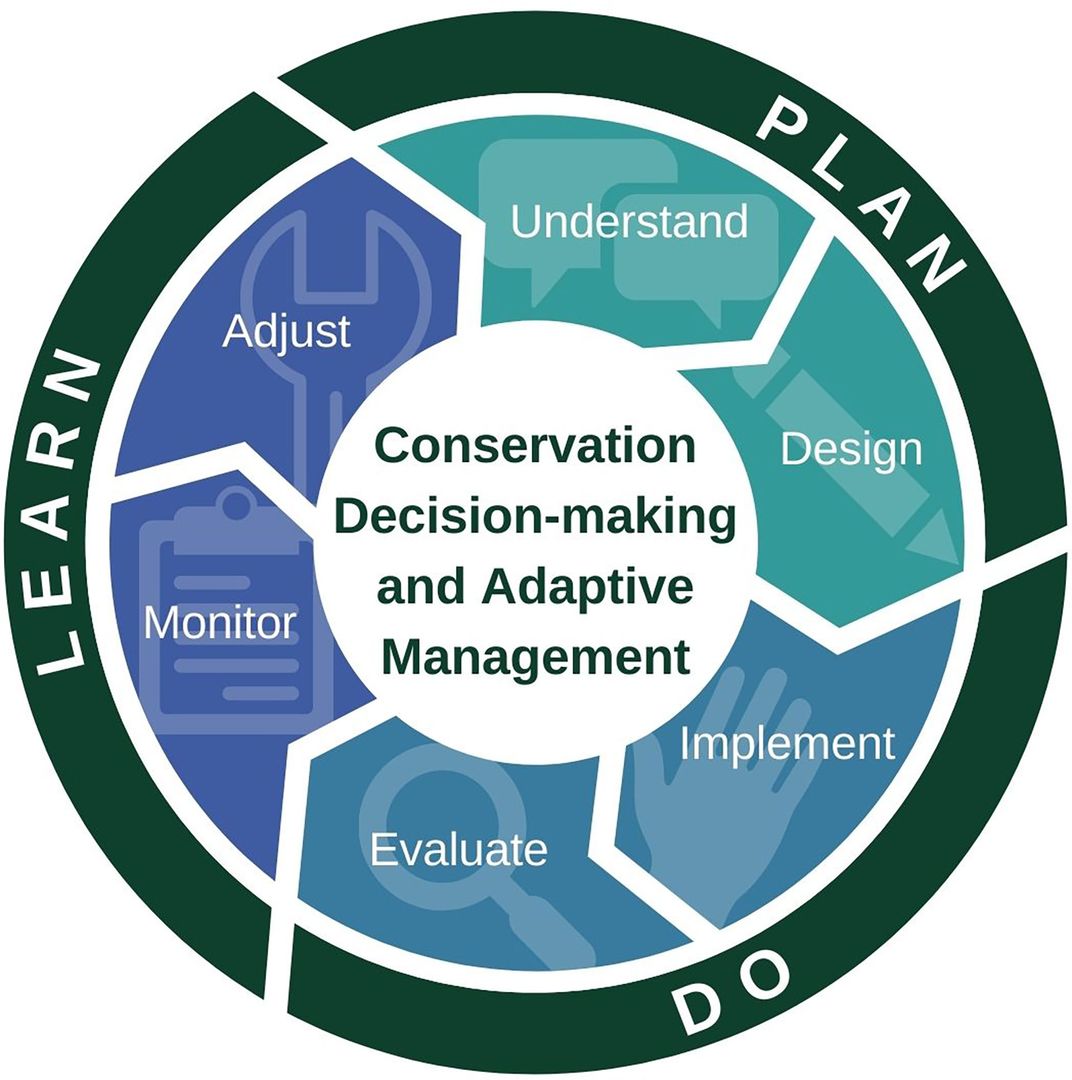

Both the place-based and theoretical topics and questions that the researchers identified can help conservation organizations strengthen the links between the ecological and socio-economic importance of their work. The publication suggests integrating these potential ideas throughout the adaptive management cycle – an iterative decision-making process of planning, doing, and learning.

During the planning phase, a project works to understand a place and design conservation approaches to match. Here, knowledge of the local context is key.

“The incorporation of social science research methods into our work has provided an immensely valuable platform to capture the views and voices of local community groups,” McNamara notes. In his work with the GBP, those community groups are local farmers, who he surveyed to better understand their perspectives on sustainable agricultural practices and other environmental issues. “The ideas and the solutions developed through guiding stakeholders in the research ensure that projects take into account peoples’ lived realities and aspirations for the future.”

Once they understand the conservation needs in the region, researchers can move on to the doing phase. Here, the social sciences can provide key insights to better evaluate and improve conservation actions, helping to bridge the gap between science, on-the-ground practice, and long-term policy – a common challenge for natural scientists.

Chiaravalloti can attest to that. For years, he and other conservationists in the Pantanal – the world’s largest tropical wetland – have been trying to scale up a sustainable certification scheme to mitigate the harmful impacts of cattle ranching in the region while still supporting their traditional practices. “Now, through our social science research,” he says, “we are finally understanding the barriers that prevented the program from thriving, which allows us to precisely tackle the key challenges.”

These evaluations help researchers transition into the learning phase of the adaptive management process, where they determine the ecological, economic, or social outcomes of their work. While each place is unique, social science provides some fundamental insights into peoples’ behaviors and motivations that can help other projects in the region – or even farther afield.

In an increasingly complicated world, that potential for wide-ranging and holistic solutions is what makes conservation social science so promising. To effectively use these more integrated approaches, though, conservation organizations need to include and support social scientists.

Many WLS projects have already seen the power of adopting this approach, with social science colleagues helping with everything from establishing more meaningful relationships with local partners to developing environmentally friendly socio-economic opportunities for communities. These actions aren’t just supporting people and the places they live in the short term – they’re also laying the groundwork for healthier and more resilient landscapes and seascapes in the long run.

Conservation social science ensures that everyone’s visions for nature – and their communities – are considered as we work together to build our shared future.