Meet Some Small Creatures That Have Big Impacts on Our Ecosystems

Protecting the little guys can lead to huge benefits for our planet.

:focal(1307x895:1308x896)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/steven-wright-mq8QogEBy00-unsplash.jpg)

What do coral polyps, mollusks, saplings, and frogs have in common? All of these relatively small organisms play a big role in their respective ecosystems, even if they’re often overlooked! Smithsonian scientists are working to better understand how they sustain our planet – as well as share that knowledge so we can make sure they’ll stick around and help future generations.

Here’s some of our favorite stories from the past month that shine a spotlight on the power of the puny:

1. Museum collections support freshwater mussel conservation

Freshwater mussels are some of the most imperiled animals in the United States, with 90 species listed under the Endangered Species Act and 35 going extinct in the past few decades. Mussels around the world are being buried by development and pollution, leaving waterways without a critical ecosystem engineer that can clean up 10 to 20 gallons of water per day. The National Museum of Natural History is home to over 240,000 mollusk specimens that can help researchers understand how mussel biodiversity has changed over time. That data can help inform restoration projects, like a partnership with the Anacostia Watershed Society that’s already released more than 24,000 mussels into the Anacostia River.

2. Diving into the history of coral reefs helps predict their future

We may not have time travel technology yet, but some Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute researchers are finding creative ways to explore the distant past – at least on coral reefs. By collecting core samples from the layers of dead coral that form the foundation of living reefs, they can create a snapshot of what life there was like long ago. From what species lived in the area over time to how the ecosystem changed in response to environmental challenges, the data they extract can help scientists and decision-makers more accurately predict the future of today’s reefs.

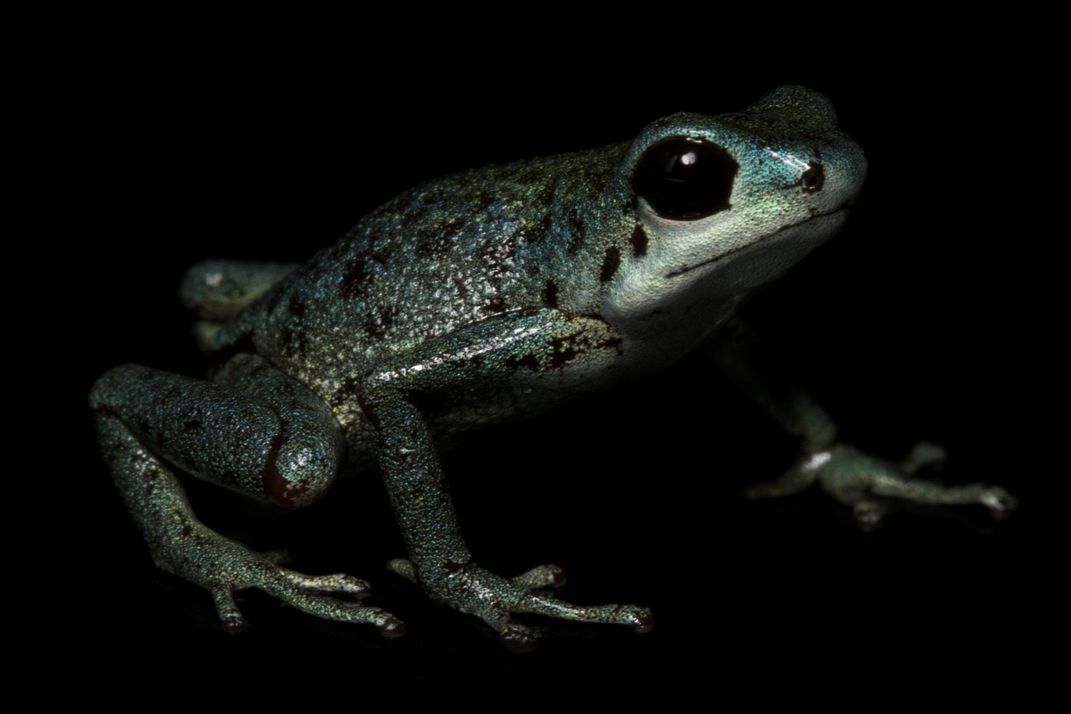

3. Toxic frogs get a better shot at surviving in the wild

In the wild, toxic frogs get their “spice” from the foods they eat. Though frogs in human care stick to diets that account for all their nutritional needs, they’ll need their protective poisons back before they’re released into the wild. Researchers at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute are testing different ways to expose captive populations of endangered Geminis’ and Vicente’s dart frogs to natural diets and behaviors, so they can be reintroduced to key habitats without being immediately picked off by predators.

4. Planting diverse tree species makes reforestation efforts more successful

In 2013, scientists and volunteers from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center and The Nature Conservancy planted 20,000 saplings on former agricultural land in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. The goal of this BiodiversiTREE experiment: monitor their growth for 100 years to better understand the role of trees in an ecosystem. One recent finding confirms that experimental plots with a variety of species have fared better than those with only one type of tree over the past decade. With so much interest in rehabilitating the world’s forests, both for the ecosystem services they provide to our communities and their potential to mitigate the harmful impacts of climate change, practices that improve the survivability and success of saplings are key to making restoration efforts count.

5. Volunteers survey oyster reefs with underwater cameras

Volunteers from across the Chesapeake Watershed are using waterproof cameras to take a closer look at oyster reefs. Everyone from local restoration organizations to concerned boaters can meet up at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center to get trained on using the research tools to keep an eye on growing oyster colonies. By monitoring the health of the reefs and their surrounding waterways, participants can monitor how effective their conservation efforts are at both reintroducing oysters and restoring the clean-up services they provide to the ecosystem.