NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

The Case of Luisa Moreno

Luisa Moreno not only organized workers in the fields and canneries, she was also a vocal advocate for Latino/a civil rights, becoming a principal leader of El Congreso de Pueblos de Habla Española (the Spanish-Speaking People’s Congress)

:focal(297x114:298x115)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/scannedpostcardmoreno.jpg)

In my first week as a curator at the National Museum of American History, I made a list of women I wished were present in the museum's collection. I scribbled on white legal pad names like Emma Tenayuca, Luisa Capetillo, Lupe Marshall, and Luisa Moreno. These were women who faced the world with complicated political voices, women who did not cower in the face of injustice, women who organized in fields, factories, and sweatshops, and understood that labor rights were intricately tied to civil rights.

I thought this was an impossible goal, but I found inspiration from other curators who told some of these stories without objects. To my amazement, Emma Tenayuca came to life through an animated cartoon in the exhibition American Enterprise. There we see a 20-year-old Tenayuca lead the 1938 Pecan Shellers’ Strike in Texas.

Although I could watch this short animation over and over, in the same exhibition hall I also saw visitors press their hands against glass cases in order to get a good look at objects, objects that seemed even more special when mounted and lit. So I began to think about the roads that might lead to the objects that would expand our collections.

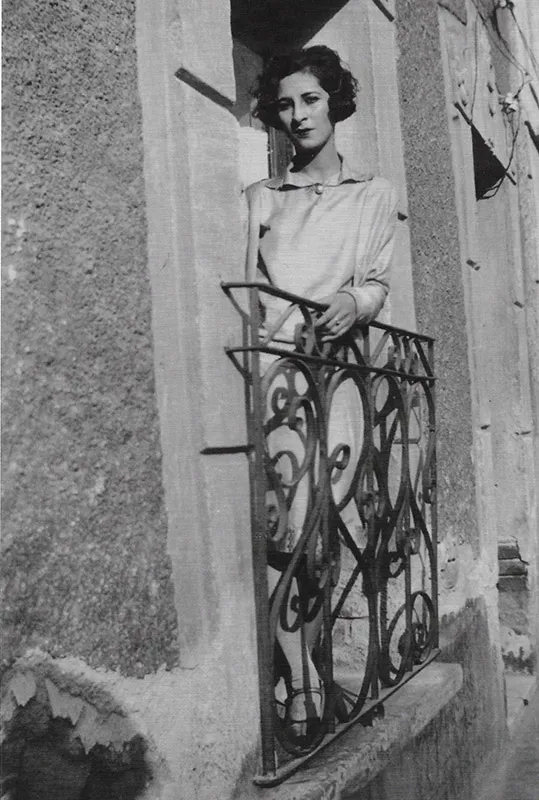

I decided to attend a lecture given by historian Vicki L. Ruiz on Luisa Moreno. Dr. Ruiz described the circuitous journey of young Blanca Rosa López Rodríguez from the upper class of Guatemala to the sweatshop floor as a seamstress in 1929 New York. Several years later, as an act of politicization, Rosa Rodríguez changed her name to Luisa Moreno. She went from a first name that means "white" in Spanish to a last name that means "dark."

Moreno was such an astute and effective organizer that in 1935 the American Federation of Labor hired her to organize Latina and African American women cigar rollers in Florida, and by 1938 she was a representative of the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA-CIO).

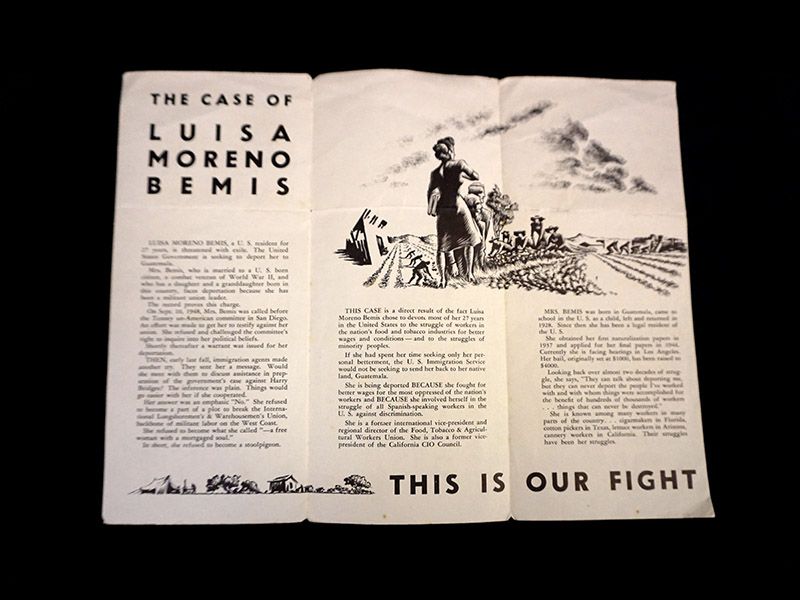

She not only organized workers in the fields and canneries, she was also a vocal advocate for Latino/a civil rights, becoming a principal leader of El Congreso de Pueblos de Habla Española (the Spanish-Speaking People’s Congress). By the late 1940s she found herself redbaited and facing deportation. In the face of imminent deportation, she left the United States of her own accord.

As I thought about Moreno, I wondered why a well-to-do, educated woman would leave a comfortable life in Guatemala City to devote her life to working-class and often working-poor communities of color. I thought about her sophisticated political perspective and the skills as a labor organizer that she took with her when she departed.

After Dr. Ruiz's lecture, I told her about my list. She said, "I have some things that were Luisa Moreno's." My jaw dropped and my eyes widened, and Dr. Ruiz said, "You can check Luisa Moreno off your list." And with that gift, Moreno's legacy is now preserved at the National Museum of American History.