NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

How Isabella Aiukli Cornell Made Prom Political

For Isabella Aiukli Cornell, a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, a prom dress was the perfect vehicle to express pride for her Native heritage and to signal her support of a growing political movement with which she has been deeply involved.

:focal(788x192:789x193)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Untitled-1.jpg)

For many high school students in the United States, prom is considered one of the most highly anticipated events of the school year. Teenagers plan months in advance on what to wear to the event, and magazines have devoted entire issues to prom fashion. Typically held in the spring, the annual dance serves as an important rite of passage for high school juniors and seniors preparing for the next stage of their lives. In the past several years, teenagers have transformed this yearly ritual into a vibrant site of politics, turning it into a platform to showcase the latest fashion and to broadcast political messages. For Isabella Aiukli Cornell, a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, a prom dress was the perfect vehicle to express pride for her Native heritage and to signal her support of a growing political movement with which she has been deeply involved.

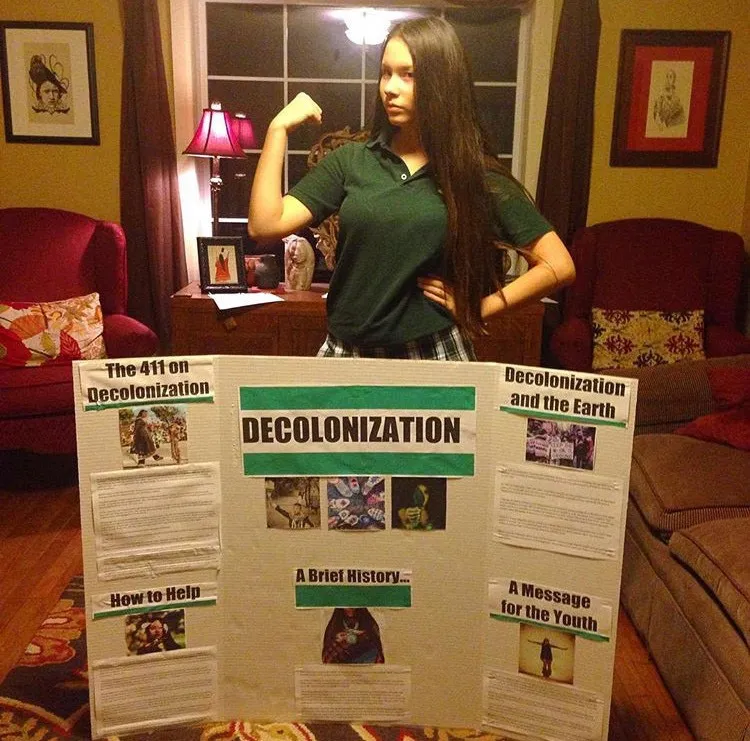

In spring of 2018, Cornell wore a red gown to her prom with the aim of raising public awareness about the ongoing epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in the United States and Canada. Her fashion choice, like many of her other activities as a girl, was an intentionally political one and part of a longer trajectory of her community activism. Since elementary school, Cornell has been involved with advocacy work, such as giving public presentations about decolonization and advocating for tribal sovereignty.

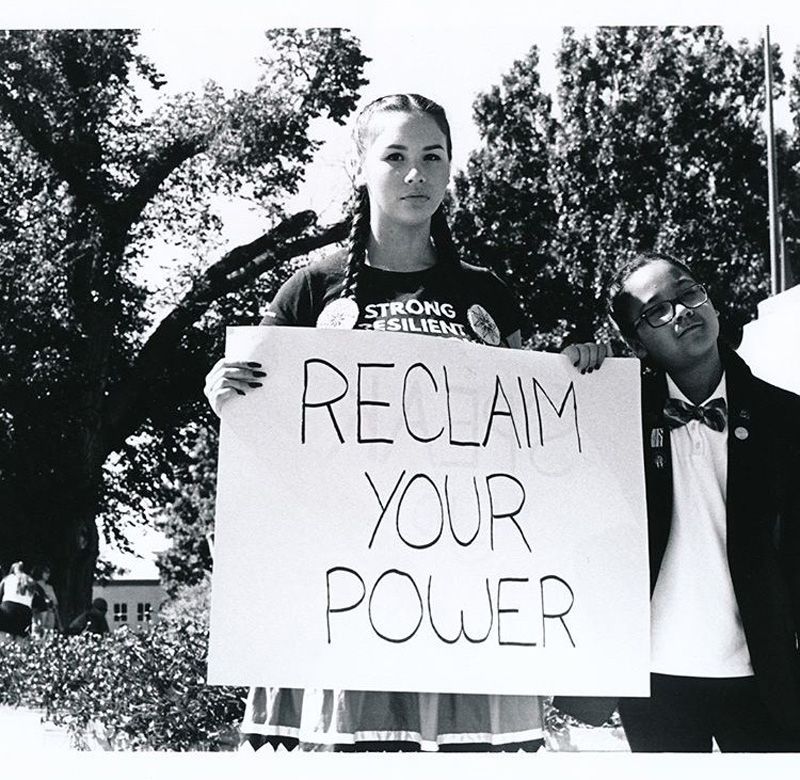

When she turned 14, Cornell began organizing alongside her mother and other Native women in Oklahoma to call attention to the epidemic of violence faced by Native American women and girls. She became an organizing member of Matriarch, an intertribal organization comprised of women from different tribes in Oklahoma, including Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Cherokee, among others. The nonprofit organization, co-founded in 2015 by Cornell’s mother, Sarah Adams-Cornell (Choctaw), and Kendra Wilson-Clements (Choctaw), provides a safe space for Native women who have faced domestic violence and other precarious situations to socialize and organize together. Matriarch’s mission is to empower women through collective networks of mutual support at the grassroots level and build Native women leaders. Members of the organization have either experienced violence themselves or are directly affected through immediate family and community relations. The organization even includes young girls, referred to as “mini-Matriarchs,” who accompany their mothers to meetings, much like Cornell did when she was a teenager.

Cornell’s decision to don a red dress for prom joins a resounding chorus of voices that have demanded local and federal law enforcement address the alarming rates of violence perpetrated against Native and Indigenous peoples, much of which is invisible to the general public. Tribal communities, community activists, artists, and allies have been organizing to bring greater public awareness to the issue and to end this systemic violence. In 2016, for example, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian hung 35 red dresses of different sizes and shades in its plaza for The REDress Project, an outdoor art installation by artist Jaime Black ( Métis) to memorialize the thousands of women who have been murdered or have gone missing. Tribal communities and the families of the women and girls have sought justice and accountability for decades, only to have their activism and voices go unheard. According to the findings of a 2016 landmark study conducted by the National Institute of Justice, more than four in five self-identified American Indian and Alaska Native women have experienced violence in their lifetime. Another report by the Urban Indian Health Institute, a division of the Seattle Indian Health Board, noted that 5,712 cases were reported in 2016, and only 116 of these cases were recorded in the database of the U.S. Department of Justice.

But this snapshot data is fragmentary and incomplete because of the lack of systematic accounting by tribal communities and local and federal law enforcement. Cornell explains that existing statistics don’t tell the full story about Indigenous women’s daily experiences of violence: “[S]tatistics are telling us that one in three Indigenous women will be victims of sexual assault in her lifetime, but we know as Indigenous people that it’s not true, that almost every single Indigenous woman, who attends Matriarch at least, has been impacted by some type of violence or assault or trauma in her lifetime. So, we know that those statistics aren’t true and that many of our women don’t actually report what happens to them.” Cornell’s explanation highlights one of the many challenges faced by tribal communities in seeking justice for those who are missing or murdered.

In November 2019, in recognition of the lack of systematic accounting, the Trump administration passed Executive Order 13898, forming the Presidential Task Force on Missing and Murdered American Indians and Alaska Natives. This task force represents a critical step in collecting data, establishing protocols for new and unsolved cases, and addressing the legitimate concerns of tribal communities regarding missing and murdered people. Further, on October 10, 2020, Congress passed Savanna’s Act (Public Law 116-165) and the Not Invisible Act (Public Law 116-166) to establish guidelines and intergovernmental coordination to help track, solve, and prevent violence and crimes on Indian lands and of Indians. Savanna’s Act provides for law enforcement coordination, data collection, and information sharing, establishing standardized protocols to respond to cases of missing and murdered Native American women. It also aims to improve tribal access to federal crime information databases. The act is named for Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, an Indigenous woman murdered in 2017.

In addition to shouldering the heavy weight of this political movement, the prom dress also symbolizes Cornell’s pride in her Native culture and heritage exhibited through various symbols and elements in the garment. The most potent symbol is the shimmery red satin fabric, which represents the color used by the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’s movement. Another important characteristic of the dress is its incorporation of traditional elements of her Choctaw culture and heritage with a modern flare. Cornell worked closely with designer Della BigHair-Stump (Crow) to create the appliqué design. The colorful appliqué is made up of satin pieces sewn together, and then applied onto the wool fabric bodice. The geometric shape, which is a Crow pattern used by Stump in many of her designs, resonated with Cornell’s vision of what she wanted to wear to prom. Cornell was drawn to the pattern because the diamond shape coincidentally symbolizes the diamondback rattlesnake, which is an important relative in the Choctaw tribe. Donor Sarah Adams-Cornell explains that the rattlesnake protected the crops of Choctaw farmers. The wool bodice evokes the long history of Native peoples who traded fur for wool cloth beginning in the early 1600s. Through the dress, Cornell wanted to convey that Indigenous girls and women are not relics of the past but are part of a culture that is thriving and future-oriented, as well as fashion-forward. Cornell’s and Stump’s sartorial vision certainly caught the fashion world’s attention when, in April 2018, Teen Vogue featured Cornell and her prom date Jalen Black in an article on how Native teens were using prom fashion to celebrate their heritage and identities.

For Cornell, a Choctaw woman, the national and international crisis of violence affecting Indigenous women and girls in tribal and diasporic communities is not a distant issue, but a constant reminder of her lived reality and those of the women and girls around her. Reflecting on why she chose the dress, Cornell explains:

“[This] dress specifically is one of the biggest pieces I think I’ve done for raising awareness, I think, because it’s very symbolic and not just my story that’s connected with but thousands upon thousands of stories that are connected with it. … But this dress, it stands for what, like, the thousands upon thousands of sisters that have gone missing over the years and how we need to bring more awareness to that.”

Cornell’s prom dress, then, represents the impactful ways in which she and many girls like her have appropriated fashion as a vehicle to speak out against social injustices. Specifically, Cornell has seized upon popular culture like prom as a platform to decry gender-based violence, a phenomenon that occurs all around us but is hidden in plain sight. Cornell’s activism and her fashion choices are a powerful testament to the ways in which girls are on the front lines organizing for change in their own creative ways and inspiring courageous conversations about social justice.

To learn more about the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’s movement, check out these two great resources founded and operated by Indigenous people: the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center and Sovereign Bodies Institute.

Cornell’s dress, now part of the museum’s permanent collection, is featured in the exhibition Girlhood (It’s complicated). Girlhood (It’s complicated) received support from the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative.