NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

Baseball Behind Barbed Wire

Prisoners in WWII Japanese incarceration camps were still American, and took part in baseball, the great American pastime

:focal(275x211:276x212)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Group.jpg)

The year was 1944. A playoff series between two all-star baseball teams generated ample excitement. Gila River fought Heart Mountain in thirteen games to win the series. The players described it as exhilarating. But the players taking part in this all-American pastime did so in dire circumstances. Gila River and Heart Mountain were both Japanese incarceration camps—previously known as internment camps—and these athletes were among the tens of thousands of Japanese Americans imprisoned there.

In 2015, the museum acquired a baseball uniform worn by Tetsuo Furukawa from this game in order to be able to tell the complex stories of immigration and settlement in the United States.

Baseball was so culturally important to the United States during World War II that President Franklin D. Roosevelt wrote a letter to Major League Baseball's commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, urging him to keep the games going even though his players may be drafted to serve in the military. Roosevelt felt baseball would give the home front a pastime and a break from the tension of war. In much the same way, Japanese American prisoners formed leagues in incarceration camps—to enjoy recreation and distract themselves from the reality of their imprisonment.

In response to Japan's bombing of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government ordered 120,000 Japanese Americans to be imprisoned in cramped and hastily built incarceration camps. They were given 48 hours to sell their homes, businesses, and possessions. They could only take what they could carry, typically two suitcases per adult. They were forced to relocate to camps surrounded by barbed wire, equipped with search lights, and patrolled by armed guards. Their draft eligibility was reassigned as 4C, enemy alien status, in the process.

"Without baseball, camp life would have been miserable," said George Omachi, a prisoner who later became a scout for Major League Baseball. Leagues formed in seven incarceration camps. Of those camps, four had teams that were permitted to travel to each other, at the expense of the prisoners. While baseball took their minds off of imprisonment, it also asserted their identity as Americans and located them within American culture.

Japanese American baseball has its roots in the 1903 creation of the Fuji Athletic Club of San Francisco. By 1910, there were so many Japanese American baseball teams that the Japanese Pacific Coast Baseball League was formed, with teams in eight large cities on the West Coast. These leagues were segregated, similar to Negro Leagues that had begun to form in the late 1800s, and were founded long before baseball was integrated in the mid-1900s. Before Japanese Americans were allowed to play in Major League Baseball, there were the Nebraska Nisei, the Tijuana Nippons, the San Fernando Aces, and the San Pedro Gophers, among others. Those early teams of Japanese Americans laid the foundation for Travis Ishikawa of the San Francisco Giants to play Jeremy Guthrie and Nori Aoki of the Kansas City Royals in the 2014 World Series.

Within the incarceration camps, professional first-generation, or Issei, baseball players would play alongside second-generation Nisei teenagers. The teens were in awe of the Issei professionals they looked up to a great deal, and the relationship furthered the next generation's love of baseball.

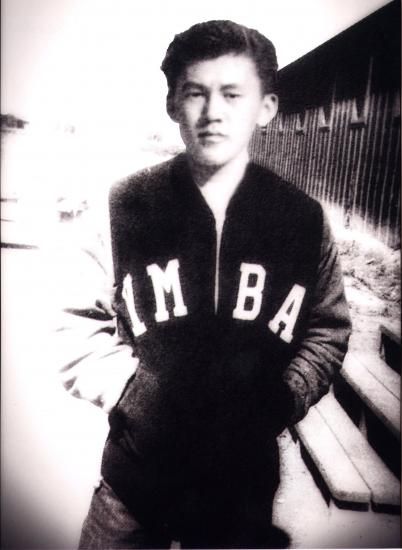

Pictures of the players and the baseball games held within the incarceration camps survive. Photographer Ansel Adams was permitted to photograph the Manzanar War Relocation Center, an incarceration camp in California, though the U.S. Army forbade him from taking pictures of the guards, the guard towers, or the barbed-wire fences. Adams wanted to create a powerful statement, but not one of despair or imprisonment, so he captured a famous photo of a baseball game while he was there. While Adams' goal was to contrast the despair, today we use his iconic photo to look at complex identities and sites of trauma.

Ten incarceration camps held 120,000 people, imprisoning them based on their ethnicity and revoking their citizenship. But those prisoners were still American. One prisoner, Takeo Suo, likened donning a baseball jersey to wearing the U.S. flag. They took part in the great American pastime, even as the U.S. government imprisoned them and questioned their place in America.