NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

Why Japanese American Alice Tetsuko Kono Joined the WAC During World War II

Japanese-American Alice Tetsuko Kono served a country that considered her an “enemy alien” and enlisted with the Women’s Army Corps during WWII

:focal(196x228:197x229)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/alice_photo_1.jpg)

Alice Tetsuko Kono was cleaning her parents' house in Molokai, Hawaii, when she heard the news about Pearl Harbor. Her radio began to chirp an urgent broadcast about the Japanese attack. She ran to tell her parents, and the family kept the radio on all day as more reports flowed in. That December day arguably changed the course of Kono's life, as it likely had the lives of many other young people of her generation. Just two years later, she enlisted in the Women's Army Corps and began a journey that would take her to California, Texas, Georgia, Minnesota, and Washington, D.C. The experience would test her mentally and physically and ultimately teach her one of her greatest lessons—"be useful." She shared her experiences in an oral history with the Veterans History Project in 2004.

When the United States declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, women were not allowed to serve in the military. As the need for personnel grew, however, the government's policy changed. On May 14, 1942, Congress passed a bill establishing the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). On July 1, 1943, this auxiliary organization was officially incorporated into the U.S. Army and became the Women's Army Corps (WAC). (For more on the history of WAAC and WAC, the army's website has background.)

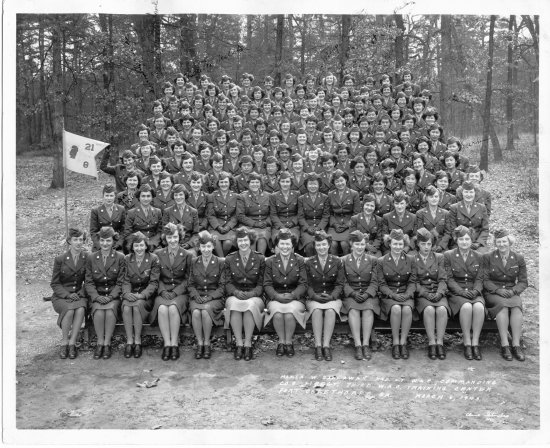

Over 150,000 American women would eventually serve with the WAC during the war. However, as "enemy aliens," women of Japanese ancestry were not eligible to join the U.S. military. This prohibition remained in place until early 1943, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved the formation of the all-Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The WAC opened enlistment to Japanese American women in November 1943.

In 1943, while on vacation in Honolulu, Kono encountered WAC recruiters. "I told my parents that I'm going to join," she recalled, admitting that her parents had mixed reactions to the announcement. According to Kono, "my dad said 'go ahead!' but my mother didn't say anything." Kono went ahead with her registration and physical exams while in Honolulu. On returning to Molokai, she informed her parents that she had passed. In a 2004 interview, Kono laughed as she recalled her parents' responses: "My mom was fit to be tied and she didn't speak to my dad for a while! . . . Because he said I was so short that he didn't think they [the army] would take me! But they fooled my dad."

During and after the war, many people questioned why Japanese Americans wanted to serve a country that considered them "enemy aliens" and had begun the process of incarcerating people of Japanese ancestry just 48 hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Over the course of the war, the federal government removed almost 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry in from the western United States into incarceration camps. As a Hawaiian resident in Hawaii, however, Kono and her family fared better than many Japanese Americans on the mainland. In 1941, over 150,000 Japanese Americans lived in Hawaii, according to "Japanese in Hawaii: a Historical and Demographic Perspective," published in the Hawaiian Journal of History in 1977. Not only did Japanese Americans constitute one third of Hawaii's total population, they also held jobs that were vital to Hawaii's economy and infrastructure. Because of these realities, the government chose not to remove Japanese Americans living in Hawaii to incarceration camps, which accounts for Kono's freedom.

Ultimately, Japanese American men and women had many reasons for serving. For Kono and many others, it was a sense of loyalty and patriotism. Kono wanted to volunteer "because my brother wasn't in the service and there was nobody in our family that was in the service, so I thought somebody should be loyal to the country." Grace Harada, who also served with the WACs, felt she "wasn't accomplishing anything" at home and wanted to help her brother, who had already joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Other men and women cited a desire to end the war as soon as possible, the opportunity to travel, and the potential for obtaining an education and developing job skills.

Kono reported for duty in November 1943 along with 58 other women from Hawaii. "There were Japanese [women], Filipinos, mixed-races, Koreans, Chinese," she recalled. They spent roughly three weeks at Fort Ruger in Honolulu before boarding the USS Madison for California. From there, they traveled by train to Fort Oglethorpe in Georgia for basic training. Kono recalls, "we had marching, physical exercises, doing all the push-ups and sit-ups, and we even had gas masks!"

From Georgia, Kono went to Des Moines, Iowa, for clerical training and lessons in relevant military terminology. From Iowa, Kono was shipped to the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) Language School at Fort Snelling, Minnesota.

As the possibility of war had grown in 1941, U.S. military officials had realized that they did not have enough personnel fluent in Japanese. They decided that Japanese Americans like Kono were the best candidates for linguistic intelligence training and began recruiting them for instruction in language schools. The basic curriculum included reading, writing, and conversation as well as lessons in Japanese army terms, military codes, and tactics. "That was intensive training," Kono remembered. "That wasn't easy. Up early and study all day, and in the evening you studied again. . . . There was more military language that we were very unfamiliar with."

Though Japan had officially surrendered before Kono graduated from language school in November 1945, she had not yet completed her 18-month enlistment period, so the army sent her to Fort Ritchie in Cascade, Maryland. For the next four months, she translated captured documents sent from the Pacific. Kono was assigned to the "air section" of the MIS, or the group responsible for translating captured documents pertaining to "planes and stuff like that." She continued that assignment after being shipped to Fort Myer, Virginia, until she returned to Honolulu and was honorably discharged.

After leaving the Army, Kono returned to Molokai and resumed her prewar job at Del Monte Foods, though she soon used her GI Bill funds to obtain secretarial training and became a company secretary. Five years later she "got kinda restless" and transferred to the San Francisco office, where she worked for the next 30 years.

In the 18 months that Alice Tetsuko Kono served in the Women's Army Corps, she traveled across the United States and received intensive training in Japanese, demonstrating admirable loyalty to a country wary of its Japanese American citizens. Without a doubt, Kono truly succeeded in her goal to "be useful."

To hear Alice Tetsuko Kono's full interview, visit the Veterans History Project.