NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

When Watchmen Were Klansmen

While Watchmen is a work of fiction, only a century ago, at the time of the Tulsa Massacre, America faced law enforcement organizations that were aligned with, and even controlled by, the Klan

:focal(400x267:401x268)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/HBO_Watchmen_blog_image_0.jpg)

Note: While history shouldn’t require a spoiler alert, this blog does contain some minor ones regarding the HBO series Watchmen.

“You know how you can tell the difference between a masked cop and a vigilante?”

“No.”

“Me neither.”

This exchange between Laurie Blake, former costumed vigilante turned FBI agent, and Angela Abar, masked Tulsa police detective, lays out a conundrum at the heart of HBO’s 2019 series Watchmen. Theirs is an America where police, costumed vigilantes, and hate groups all wear masks to protect their “secret identities,” where anonymity leads to the corruption of power, and where those identities become dangerously blurred. The show is an “extrapolation” based on the groundbreaking comic series created in 1986 by Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and John Higgins, in which the introduction of masked vigilantes— real-life “superheroes”—in 1938 creates an alternate history. The series sees that history play out in strange and uncomfortably familiar ways.

HBO’s Watchmen has drawn critical acclaim, particularly for its grounding in the historical reality of the 1921 Tulsa Massacre, a violent racial pogrom against that city’s prosperous Black enclave of Greenwood. This jarring and brutal real-life tragedy leads directly to the alternate timeline of Watchmen, and it underpins its examination of the lines between law enforcement and vigilantism, the threat of white supremacy, and the danger of “justice” that wears a mask (or a hood).

Police forces both past and present are shown to be infiltrated by the Ku Klux Klan and its fictional successor, the Seventh Kavalry. And while Watchmen is a work of fantastical fiction, only a century ago, in the period of the Tulsa Massacre, America faced a similar but true dilemma. Our own history includes some law enforcement organizations in the early 1900s that were aligned with, and even controlled by, the Klan.

William J. Simmons, a former minister and promoter of fraternal societies, founded the second incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia in 1915. His organization grew slowly, but by the 1920s, Simmons began coordinating with a public relations firm, in part to chip away at the (accurate) perception that the Klan was an outlaw group involved in extralegal violence. Membership in the Klan exploded over the next few years. As part of this PR campaign, Simmons gave an interview to the Atlanta Journal newspaper in January 1921. While explicitly advocating white supremacy, Simmons played up his group’s commitment to law and order, promoted their enforcement of Prohibition, and even boasted of his own police credentials. He claimed members at every level of law enforcement belonged to his organization, and that the local sheriff was often one of the first to join when the Klan came to a town. Ominously, Simmons declared that “[t]he sheriff of Fulton County knows where he can get 200 members of the Klan at a moment’s call to suppress anything in the way of lawlessness.”

Across the country, the Ku Klux Klan sometimes claimed it was protecting the public when the police could not. However, its leaders also often sought to legitimize the organization by working in cooperation with police—a strategy that has echoes in the Watchmen series. Writing on the early 1900s revival of the Klan, historian Linda Gordon recounts numerous collaborations between police and the Klan in the 1920s. In Portland, Oregon, the Klan formally allied itself with the police department, and city’s mayor augmented the 150-man police force with a vigilante auxiliary selected by the Klan, giving them police powers and guns but keeping their names secret. In Anaheim, California, the Klan-dominated city council allowed police officers who held membership to patrol in full Ku Klux Klan regalia. And in Indiana, the Klan exploited a decades-old legal loophole to gain a legitimacy that only a badge could bring.

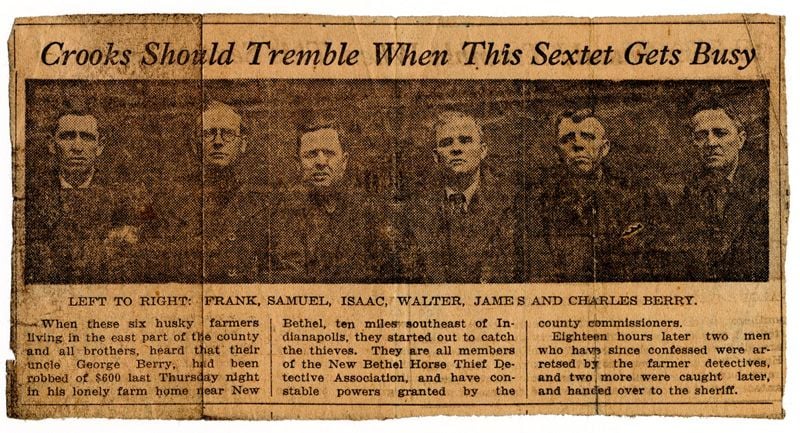

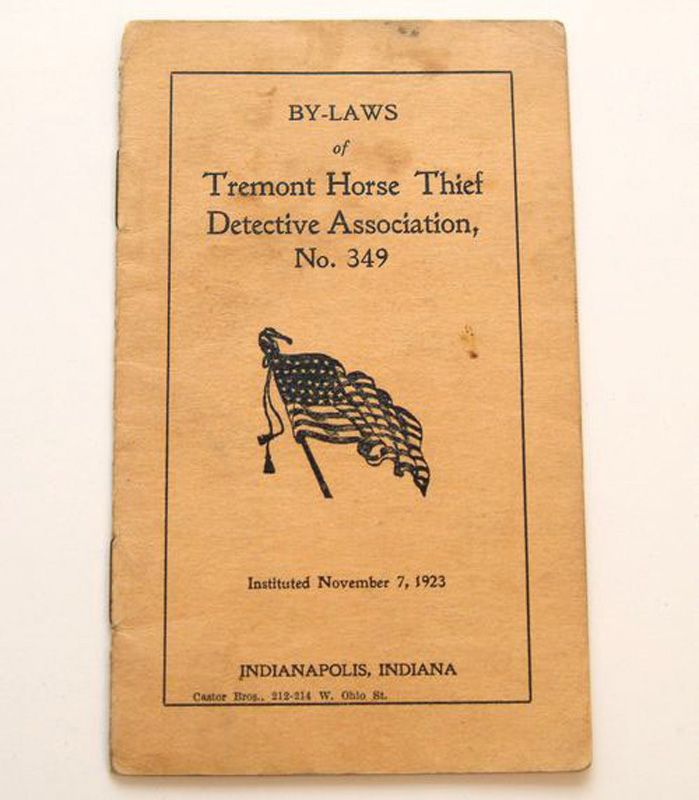

Indiana had a long and established tradition of sanctioned vigilante organizations, dating back to the 1840s. In the second half of the 1800s, the state established laws allowing citizens to form chapters of the Horse Thief Detective Association (HTDA) that, once approved by their county, were commissioned to protect property. Members were provided legal authority to investigate crimes and arrest suspects. With the advent of the automobile in the first decades of the 1900s, membership in these groups declined. However, by the 1920s, their numbers rebounded and grew—with new chapters arising, sometimes four or five in a single county. Estimates put peak HTDA membership at around 20,000 throughout the state.

The odd revival of the Horse Thief Detective Association, in a period when horses had been supplanted by cars and trucks, was no mystery at the time—the system had been co-opted by the KKK, and the two groups became closely entwined. Historian Thomas Pegram has noted that HTDA chapters would give activity reports at Klan meetings and Klan funds were used to support HTDA activities. Indeed, the Indiana Klan held out honorary memberships to any commissioned member of the HTDA, offering reduced dues as an incentive. As sworn members of HTDA chapters, Klansmen in the state essentially formed an armed, officially sanctioned force that would allow them to enact their agenda under the guise of legitimate law enforcement.

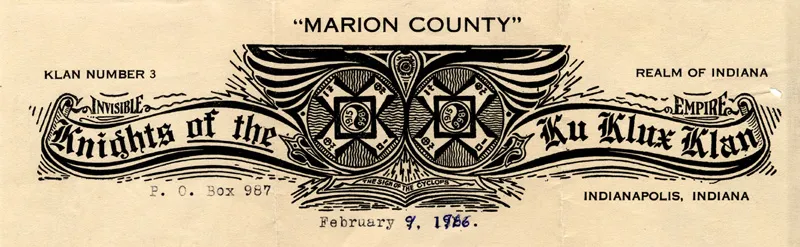

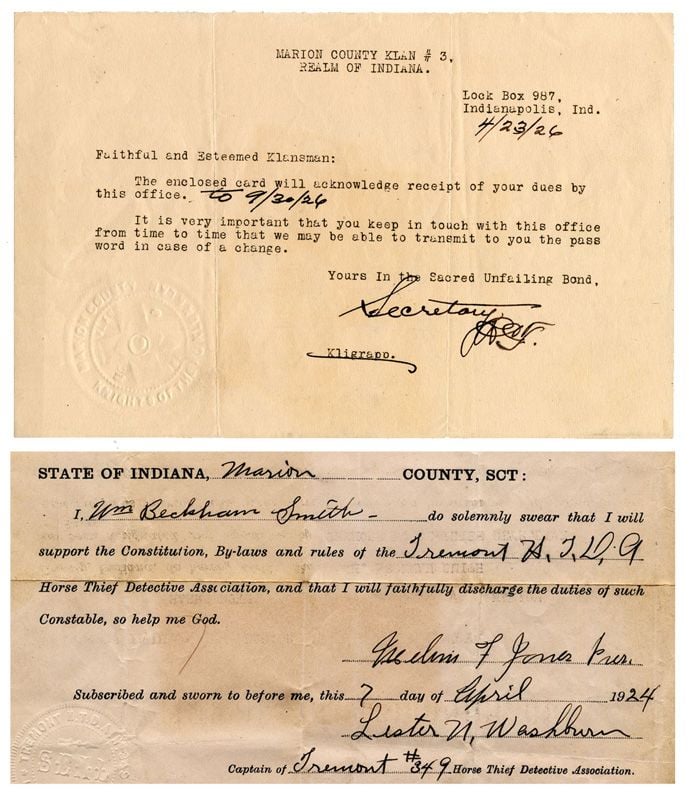

In his work on the Klan in Indiana, historian Leonard J. Moore details membership records from 1925 that show over 20 percent of the state’s eligible population—white, Protestant, native-born males—belonged to the organization. In some counties, that number exceeded 33 percent. In Marion County, which included the city of Indianapolis, over a quarter of eligible men belonged to the Ku Klux Klan—some 25,000 members in total, many of whom held dual membership in their local HDTA chapter. One such member was William Beckham Smith, who joined the Tremont Horse Thief Detective Association of Marion County, Indiana, in April 1924. His HTDA badge and membership material are held in the museum collections, and the museum’s Archives Center has items related to his membership in Marion County Klan Number 3.

As Horse Thief Detectives, the Indiana Klan came down on bootleggers, organized labor, immigrants, and African American populations. In one incident, related in Elliot Jaspin’s book Buried in the Bitter Waters, they helped to expel Black citizens from the mining town of Blandford in western Indiana. On January 18, 1923, a young girl from Blandford reported she had been abducted and assaulted by an African American man. Within 48 hours, several hundred white townsfolk met and demanded that all Black residents leave, beginning with unmarried men, who were to be outside town limits by that evening. Within a week, all Black residents of Blandford—approximately 50 people—had fled. That exodus was overseen by Harry Newland, the sheriff of Vermillion County and himself a Klansman, along with members of the Dana HTDA and the Helt Township HTDA, two of the four chapters in the area. The Helt Township chapter alone included over a dozen members of the Klan, including its captain. African American citizens, both in Blandford and the surrounding county, felt forced to comply and departed en masse. As Jaspin notes, the 1920 census recorded well over 200 Black residents in Vermillion County—in 1930, that number was less than 70. Such racial cleansings were not always as savagely violent as the Tulsa Massacre, less than two years prior, but could be just as devastating in the long run.

In HBO’s Watchmen, high-tech plots by Klansmen both past and present are eventually thwarted by the intervention of masked vigilantes. In our history, the Klan of the 1920s essentially thwarted itself. In Indiana and elsewhere, the Klan was riven with numerous abuses and political, criminal, and sexual scandals among the group’s leadership. Public opinion soured and membership plummeted, though not until after a decade of virulent rhetoric, racial terrorism, and violence. Without the Klan’s participation, HTDAs faded by the 1930s. Of course, bigotry and religious intolerance did not disappear along with this second version of the Klan—a third iteration would take hold in the postwar civil rights period, and strains of organized white supremacy continue to operate and network, using the internet to preserve anonymity as hoods and masks once did. In offering its own strange alternative history, Watchmen invites us to examine our own past and present and answer for ourselves another crucial question: Quis custodiet ipsos custodes—“Who watches the watchmen?”

The documents and objects in this blog post come from the Warshaw Collection of Business Americana in the National Museum of American History's Archives Center and the Division of Cultural and Community Life.

If you’d like to read more about the rise and fall of the Ku Klux Klan in the early 1900s, some of the sources cited in this blog include:

Buried in the Bitter Waters: The Hidden History of Racial Cleansing in America by Elliot Jaspin (Basic Books, 2007)

Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921–1928 by Leonard J. Moore (Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1997)

One Hundred Percent American: The Rebirth and Decline of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s by Thomas R. Pegram (Ivan R. Dee, 2011)

The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition by Linda Gordon (Liveright Publishing Corp., 2017)

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on April 28, 2020. Read the original version here.