NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

Mary Walker, the Original “New Woman”

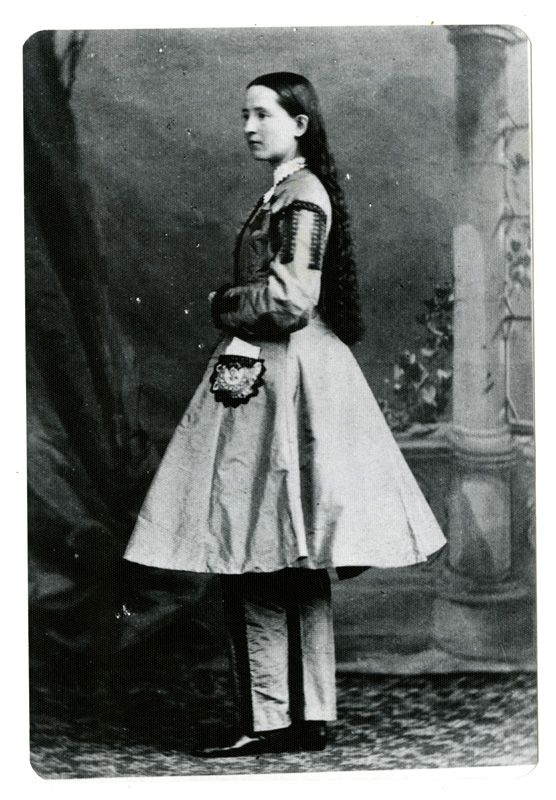

Walker described herself as “the original new woman,” referring to an emerging term for an independent woman who stood up for herself, regardless of social roles.

Mary Edwards Walker defied convention in just about everything she did. Walker was uncompromising in her beliefs about herself and the world she lived in. She declined to conform to social expectations, which sometimes cost her greatly; until her dying day Walker refused to be anyone but herself, a trait even some of her detractors eventually came to admire. In an 1897 interview, Walker declared herself “the original new woman." She certainly broke society’s molds.

Walker was born in 1832 into a world where women’s roles were clearly defined. Growing up near Oswego, New York, Walker had an unconventional family that set the precedent for her life. Her parents believed in equal education for both sexes, as well as equal distribution of labor on the family farm. The six Walker girls were encouraged to wear bloomers (a shortened dress and pants) instead of traditional skirts because their parents believed the freedom to move was healthy, and more important than social decorum.

Walker worked in the traditionally feminine role of teacher, but her heart was in the then-masculine world of medicine. She saved her teaching wages to pay for medical school, then left for Syracuse Medical College. In 1855 Walker graduated as one of the first woman physicians in the nation. (The first woman to graduate from medical school in the United States was Elizabeth Blackwell, six years earlier.)

The same year of her graduation Walker married a fellow medical student—unconventionally, of course. Walker retained her own last name and wore a dressy bloomer suit for the ceremony. The marriage didn't last. Four years later, she began a nine-year quest to obtain a divorce from her philandering husband. Though divorce was legal at this time, it was considered a social disgrace, one Walker bore throughout her life.

Walker was making a meager living as a physician. Many patients were distrustful of a woman doctor, and it was a struggle to maintain her practice. In her spare time Walker also published essays and began lecturing publicly, with her topics focusing on various types of social justice, particularly dress reform and women’s rights.

When the Civil War began in 1861, Walker, a staunch abolitionist, traveled to Washington, D.C., to volunteer her medical services for the Union. She was told she couldn’t officially join up as a doctor due to her gender. Undeterred, Walker made the rounds at Washington, D.C., hospitals, volunteering where she could, even traveling directly to battlefields. Finally, in 1863, Walker was assigned to a contract position as a surgeon with the 52nd Ohio Volunteers. This made her the first woman physician employed by the United States military.

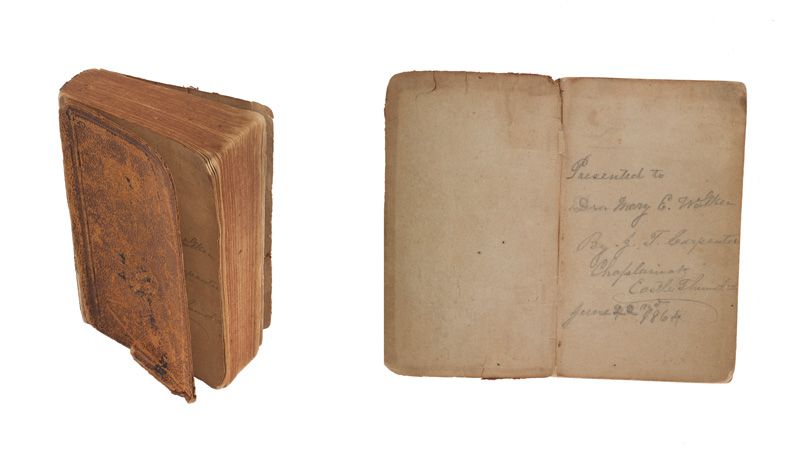

Walker set off in a bloomer uniform of her own design. After only a few months, she was captured and held as a Union spy after crossing battle lines to treat civilians in Confederate-held territory. She was held for over three months in Castle Thunder, a notorious prison near Richmond, Virginia. At the war’s end, Walker was presented with the Congressional Medal of Honor for devoting “herself with such patriotic zeal to the sick and wounded soldiers.”

After the war, Walker campaigned on behalf of a variety of causes, including worker’s rights, veteran’s compensation, and above all, women’s equality. She increasingly undertook targeted, conventional forms of activism such as lecturing and writing, in addition to living activism via her unconventional lifestyle and actions. As early as 1871 Walker attempted to register to vote, though she was denied. She planned suffrage campaigns with Belva Lockwood (an activist who was one of the first woman lawyers in the United States) and was an active participant in the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Unlike Anthony and Stanton, however, Walker argued that there was no need for a constitutional amendment for woman suffrage. Rather, she believed that the constitution already granted women the right to vote as citizens; Congress simply needed to recognize this fact.

Walker’s outspoken opposition to the constitutional amendment the NWSA would fight for, as well as her radical views on divorce and women’s clothing, led many suffrage leaders to distance themselves from her. She is not mentioned in the official pages of the woman suffrage movement, History of Woman Suffrage, as written by Anthony, Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage. Though ostracized from the main movement, Walker continued to work for woman suffrage, as well as her other causes, through the rest of her life.

Each form of Walker’s service to her ideals came with trials. She was physically attacked and arrested multiple times for wearing pants in public. She was called unnatural for her interest in practicing medicine as a woman. Her character was maligned in newspapers each time she dared to speak publicly in favor of her principles. Even her fellow suffragists refused to acknowledge her. But Walker never stopped working for what she believed was right. In 1917 Walker’s Medal of Honor, along with those of over 900 men, was revoked when Congress declared that non-combatants were ineligible for the award. Given Walker’s stubbornness in the face of adverse reactions to her choices, it should perhaps not have surprised anyone when Walker simply refused to return it. Rather, she wore it for the rest of her life.

By the time of her death in 1919, Walker’s and others’ perseverance had borne fruit in many ways. Slavery had been abolished, Paris fashion houses had introduced harem trousers for women, and woman suffrage was gaining traction (the Nineteenth Amendment would be ratified 18 months after her death). If Walker was not the “original new woman,” she was certainly one of the first, paving the way for the pants-wearing, voting, activist “new women” of the future.

In 1977 Walker’s Congressional Medal of Honor was posthumously reinstated. She remains the only woman to have ever received one.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on March 25, 2020. Read the original version here.