NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

The Most Radical Thing About Stonewall Wasn’t the Uprising

Much of the staying power of Stonewall’s reputation rests upon the Pride marches that began on the first anniversary of the uprising.

:focal(800x600:801x601)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/fedempl.jpg)

The Stonewall uprising began June 28, 1969, in response to a police raid at The Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York, and has since been commemorated around the world with pride parades and other events.

I’m a Stonewall skeptic. I don’t doubt that it happened, but I question how it has been used over the years. Because this is a big anniversary year, there is a compulsion to heroize the people who were there and elevate the event.

Those sweaty summer nights of rebellion were certainly important and unique and have reverberated for 50 years. However, an event like the Stonewall uprising was inevitable—young people with 1960s political impatience and righteous indignation had a lot of LGBTQ+ history to fuel them. Other protest and resistance had already happened in places such as Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Much of the staying power of Stonewall’s reputation rests upon the Pride marches that began on the first anniversary of the uprising.

Stonewall’s outsized fame has a downside—skewing both understanding of LGBTQ+ history and misrepresenting how historical change comes about. There is no universal LGBTQ+ history in which any one event is primary. The only commonality in LGBTQ+ life is the risk people take in being themselves.

Stonewall is often pointed to as the birth of the modern gay rights movement or the biggest news in LGBTQ+ history. But that is not accurate. For many gender-non-conforming people, Stonewall had little effect or held no interest. For many disabled LGBTQ+ people, change has been glacial—many people were institutionalized in the 1960s and still constitute a large percentage of those incarcerated. The largest psychiatric facilities today are prisons. In the 1960s, many people of color were putting their energy into civil rights work, antiwar activism, or the Chicano Movement. People living in small towns and rural areas outside of the metropoles of New York, San Francisco, or Chicago did not hear about what happened in New York City or take it up as a rallying cry.

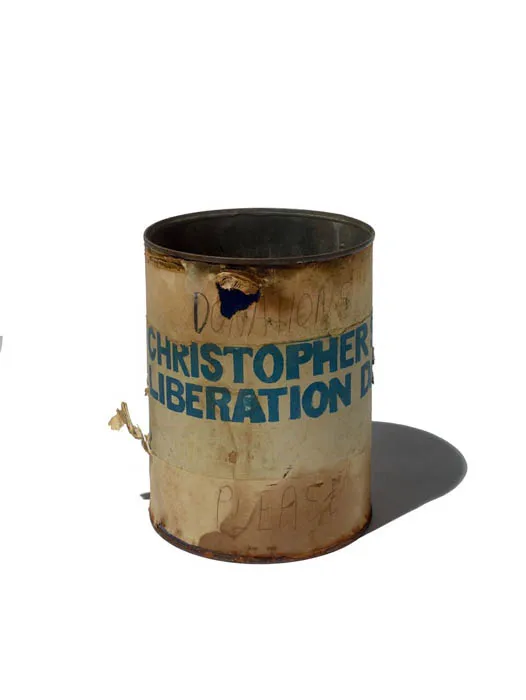

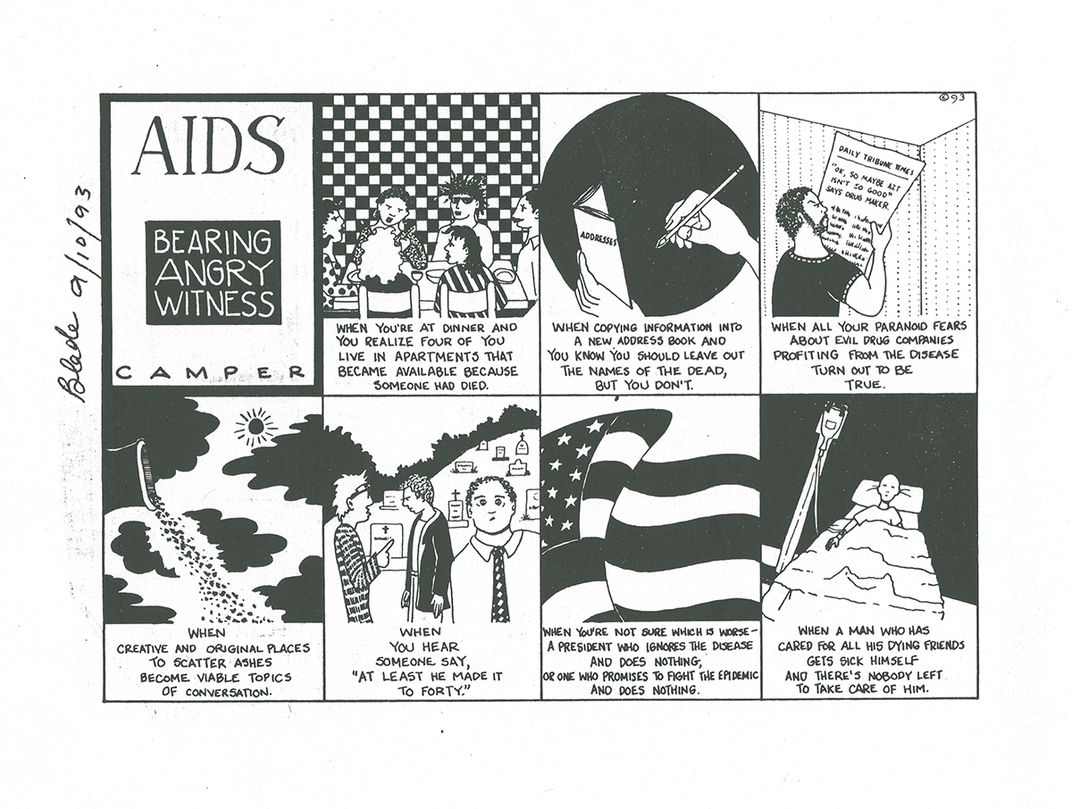

Some 12 years after Stonewall, the AIDS epidemic more broadly modernized the gay rights movement and propelled gay liberation by decimating and restructuring communities, creating solidarity, and necessitating out-of-the-box confrontations.

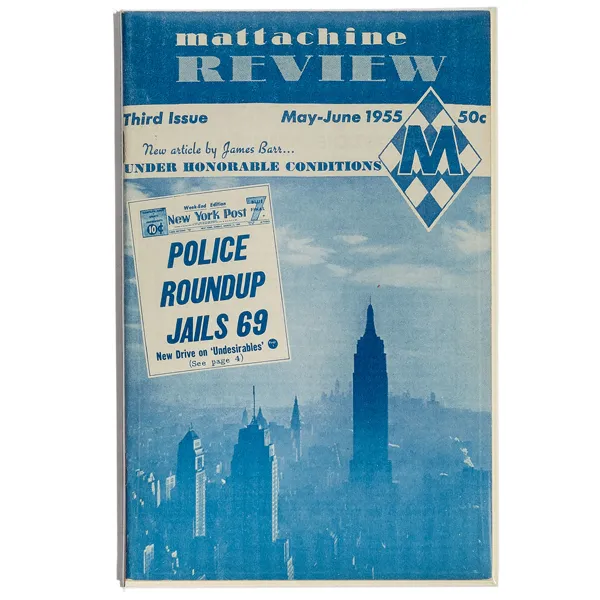

We often think of history with testosterone-fueled events such as battles, riots, and assassinations being the source of lasting change. Violent outbreaks are dramatic and the pain that comes in their wake is attention-grabbing. But real change generally does not come about in a moment. It happens over time and is sustained by people who hold on to an idea and push it forward: the World War II soldiers who came out to each other and stayed out, the 1950s and ’60s journalists who mailed their newsletters in plain brown wrappers, the court cases, picketing, cafeteria rebellions, and everyone who showed up to challenge ignorance. Before Stonewall, there were dozens of legal actions around jobs, marriage, housing, and the right to be yourself. Violence may accompany change, but it does not sustain it.

For me the reason to remember the Stonewall uprising is in recognition of the daily acts of courage the rioters took that got them to the bar that night. It is the multiple, unremarkable moments of inbreathing “Yo Soy, I am” that people on the margins take every day that is the watershed for change.

A display titled Illegal to Be You: Gay History Beyond Stonewall is currently on view at the museum.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on June 21, 2019. Read the original version here.