NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

Why Did the Smithsonian Collect a Handwritten Note from 9/11?

In moments of crisis, our first thoughts are usually to get in contact with the people we love.

:focal(365x212:366x213)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/note_excerpt.png)

In moments of crisis, our first thoughts are usually to get in contact with the people we love. September 11, 2001, was a day when many people wanted to know that their loved ones were safe. At 9:37 a.m. the Pentagon was attacked by terrorists who crashed an airplane into the western side of the building. This was one of four airplanes that were hijacked that morning; two attacked New York City and a third crashed in Pennsylvania. Many people tried using the mobile phones that existed then, but few were successful. One couple at the Pentagon relied on pen and paper as the means to communicate with each other.

Cedric Yeh, curator of our national September 11 collection, recently collected a handwritten letter from Daria "Chip" Gaillard to her husband, Franklin, both of whom worked at the Pentagon. A handwritten note might seem outdated to us in the digital era, but on that day a note provided peace of mind in the midst of chaos for this couple.

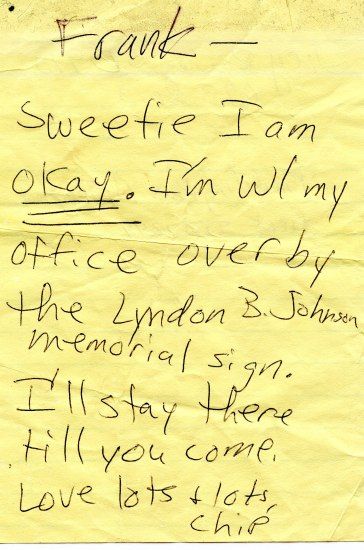

Frank and Chip were both members of the Air Force and worked at the Pentagon. They worked in different parts of the building from where the attack occurred. Regardless, they evacuated and had a previous agreement that they would meet at their car in the parking lot if there were any emergency. Daria was the first to arrive at the car and wrote a note to Franklin saying "Frank—Sweetie I am okay. I'm w/ my office over by the Lyndon B. Johnson Memorial Sign. I'll stay there till you come. Love lots & lots, Chip."

Frank found the note and was able to locate his wife in the aftermath of the attack on the Pentagon. Not everyone was as fortunate as the Gaillards on September 11. Once the couple knew they were safe, they turned their attention and efforts to others. The child daycare center of the Pentagon was evacuating in the same area, and the Gaillards helped move the children to safety. Their focus on the safety of the children was one of many unselfish acts in the aftermath of the attacks that morning.

What makes this story so interesting is the handwritten note. Today in our digital culture we have a variety of ways to let people know that we are safe. Text messages, voicemail, and different forms of social media can be used to get the information out to loved ones. Facebook's Safety Check feature, for example, is a quick way for people who are located in a disaster area to tell their friends and family that they are safe. But these all require a working cell phone network in order to be successful.

When these attacks happened in 2001, the cellular network was still growing and was not as robust as it is today. The people who had cellphones had trouble getting calls through, and the only other type of mobile communication were beepers, which have their own limitations.

In the case of Franklin and Daria Gaillard, going low-tech served them well. In a moment when technology may have failed them, pen and paper did not. This letter is just one of the many objects that the museum has collected since 2001. To learn more about the objects collected, visit our online exhibition September 11th: Bearing Witness to History.

To commemorate the 20th anniversary of the attacks, the museum is hosting a series of programs exploring their lasting impact. The museum is also launching a story collecting project—share your 9/11 story with the Smithsonian here.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on September 8, 2016. Read the original version here.