NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

Essential or Expendable? How the UFW Fights for Farmworkers

Agricultural labor is often overlooked, but it is critical to understand its history, especially as COVID-19 shines a light on unchecked abuse and exploitation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/df/43/df43f639-ff54-4278-9949-c69d06ea4257/ufw_poster.jpg)

Until the successes of the United Farm Workers (UFW) in the 1960s, agriculture was one of the last industries to hold out on unionization due to social and legal obstacles. Workers and organizers faced uneven legal protection; isolation; prejudice; reliance on imported, exploitable workers; and opposition from state and federal officials who either represented agribusiness or were themselves major agricultural landowners. U.S. laborers, agricultural and otherwise, continue to face these challenges today. Despite union victories of the 1800s and 1900s, such as child labor laws, the eight-hour workday, and the five-day workweek—i.e., creation of the weekend—there are still movements aimed at undermining workers’ rights in the United States. Agricultural labor is often overlooked but it is important to examine its histories, especially as COVID-19 shines a light on issues rooted in the past that are still present in agriculture and other areas of society.

Agriculture’s workers often come from marginalized communities and are thus highly vulnerable to unchecked abuse and exploitation, which stalled unionization. Due to their marginalization and the rural and isolated nature of their work, laborers lived and worked under the pleasure of growers and agribusinesses. There were no watchdog organizations interested in how agricultural workers were treated, and if labor laws existed, they were often not enforced. In the South, sharecropping and the racial and structural legacy of slavery made it impossible for large-scale organization. Lynching, segregation, and other racial terror and policing tactics maintained a racial status quo to the detriment of Black and non-white citizens. In the West, many agricultural laborers were immigrants, and deportation—for documented and undocumented workers—was used as a threat. Even when unions and collective bargaining were granted some legal protections—as with the enactment of the National Labor Relation Act in 1936—agricultural workers were excluded from its protections.

Pre-UFW agricultural organization was sporadic and met with fierce aggression. There were about 30 attempted strikes in the California’s San Joaquin Valley from 1931 to 1941, but they were violently suppressed by growers and local law enforcement. In 1938 20-year-old tejana Emma Tenayuca organized a successful strike of pecan shellers in San Antonio, Texas, with the help of professional organizer Luisa Moreno. Moreno worked with a variety of unions but was forced by deportation threats to flee the United States in 1950. The Latina labor activist was denounced as a subversive communist threat to the country. Nonetheless, these movements and their leaders shaped and inspired future generations of organizers and activists.

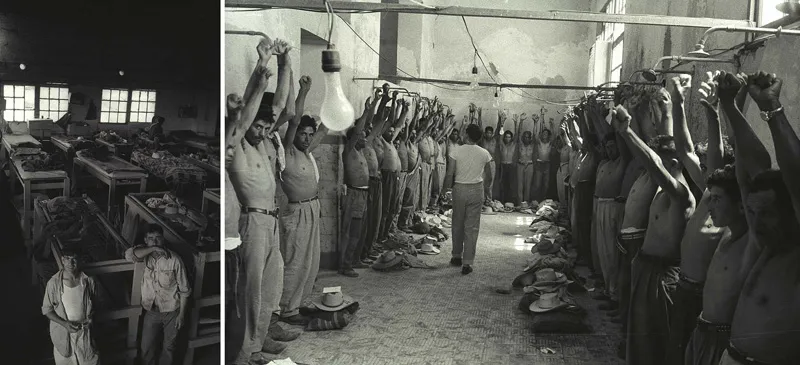

The Bracero Program also blocked effective unionization. Agreements between the United States and Mexico between 1942 and 1964 annually imported about 200,000 temporary Mexican agriculture workers, called braceros. Despite legal promises, growers mistreated and underpaid braceros, arbitrarily withheld their pay, and threatened them with deportation for protesting. The Bracero Program ended, in part, because U.S. leadership was forced to act on the reality that the presence of the exploited braceros depressed the earnings of U.S. farm labor to the sole benefit of growers. Growers, in response, unsuccessfully attempted to turn to mechanization as a replacement for braceros. It is no coincidence that unionization spread through the agriculture industry within the decade the Bracero Program ended.

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw the emergence of agricultural unions, such as the Filipino Farm Labor Union, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), the Agricultural Workers Association, and the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), which merged in 1966 with other unions to become the United Farm Workers. They demanded improved pay and conditions. Child labor was rampant. Growers often failed to provide bathrooms for workers, and the housing growers provided—which the underpaid laborers were made to occupy, at exorbitant rates—frequently had no plumbing or cooking facilities. Overwork and lack of safety posed major health risks. The average life expectancy of a farmworker in the 1960s was 49 years, a stark contrast to the national average life expectancy of 67 years.

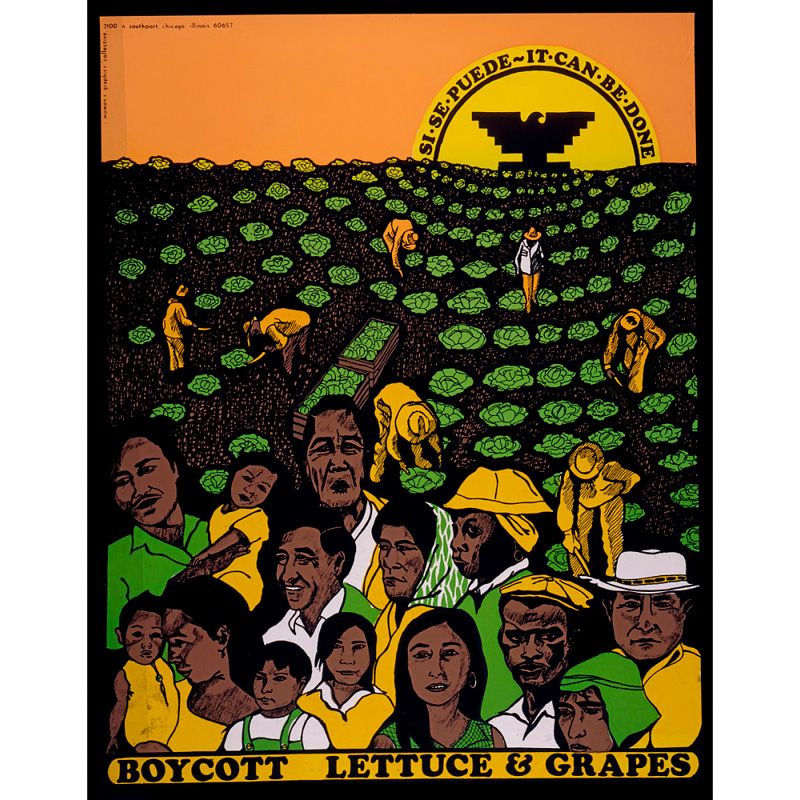

The UFW’s first major strike was the boycott and strike of grape growers in Delano, California, from 1965 to 1970. Larry Itliong began the strike with over 1,000 Filipino farmworkers from AWOC. Grape growers attempted to pit newly hired Mexican workers against the Filipino workers, but Itliong reached out to Cesar Chavez and the NFWA for help. The peaceful protests of Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi inspired the actions and strategies of union leaders such as Chavez, Itliong, and Dolores Huerta. The UFW led peaceful pickets of the grape fields, convinced strikebreaking workers to join the strike, marched 300 miles to Sacramento, and organized grassroots and community boycotts of grapes and grape products throughout the United States. These efforts were highly successful and resulted in the first-ever contracts between growers and an agricultural union. These contracts raised wages 40% from the still-used standard Bracero wage and improved working conditions; some included paid vacation and insurance.

Though the museum’s UFW collection centers on Cesar Chavez and the union’s work in the 1960s and 1970s, the UFW continues to exist and fight for farmworker rights. Since 2000, UFW membership has doubled and the UFW has fought against wage theft, sexual harassment, and more. Recently, COVID-19 has further revealed farmworkers’ lack of broad protections: many agribusiness companies give only supervisors masks and are not enforcing safety measures though studies show that farmworkers are among the highest risk of contracting COVID; there are many cases of farmworkers being fired for protesting following COVID outbreaks among workers; laborer families make an average of less than $20,000 annually; and farmworkers are often not given sick leave, with 65% of workers not having any health insurance.

Unlike workers in many other essential fields, farmworkers are out of the public eye, isolated due to the nature of their job. It is also a very racialized field, about 72% foreign-born, almost all from Latin America. This examination of the roots of agricultural unions is important because it demonstrates the reach of historic legacies and injustices and how obstacles and issues of ‘back then’ are still shaping our world today. If their labor is essential but the worker is not, how is worker value determined? COVID-19 has exacerbated these issues, which requires much further discussion and reflection.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on October 15, 2020. Read the original version here.