NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

Maggie of the Boondocks

In the Mekong Delta, there was nobody who could pick up your spirits like USO girl Martha Raye

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5f/24/5f24ce88-ede9-414d-a2a8-33191d4cbfe6/lt_carr.jpg)

Around 1966, Dr. Carl Bartecchi was serving as an army flight surgeon in the Mekong Delta in South Vietnam. When units in his area engaged in heavy combat with a Viet Cong force, Bartecchi found himself treating wounded men in rapid succession. In the operating room he heard a woman’s voice, “a sound that was somewhat unusual for our area,” he recalled. She told him “Don’t worry, I know what I am doing,” and went along cleaning out wounds for several hours before stepping out to donate blood for a critically wounded man. The same woman, hours later, could be found among the stretchers of wounded soldiers, cracking jokes, teasing, talking, and lifting spirits. That evening, she put on a performance for the base that brought the house down.

“I didn’t know then that she was at other locations in the Mekong Delta, in places where you usually didn’t go,” Bartecchi said. “Yet, these are the places that people like Martha were most needed, and there was nobody who could pick up your spirits like Martha Raye.”

Martha Raye, born Margy Reed in Butte, Montana, in 1916, entertained audiences on stage, television, and the silver screen for over 60 years. She began her career in vaudeville at age three and matured into a talented vocalist, dancer, and comedian. She burst onto the national scene in the 1930s on Broadway and in Hollywood. Raye’s musical skills meshed with talent for physical humor and her famous “big mouth” smile in performances alongside such greats as Steve Allen, Charlie Chaplin, Bing Crosby, W. C. Fields, Judy Garland, Bob Hope, and Rock Hudson.

When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, Raye’s life would change forever. She joined the fledgling United Service Organizations (USO), which brought together several welfare organizations to provide recreation and various morale-building services to the U.S. Armed Forces. In late October 1942, Raye partnered with fellow entertainers Kay Francis, Carole Landis, and Mitzi Mayfair for an overseas tour, which took them to England and North Africa. In between shows, Raye, having trained as a nurse’s aide in Los Angeles, helped military medical personnel in field hospitals. After her colleagues returned home, Raye carried on by herself until yellow fever and anemia forced her return to the states in March 1943.

The experience gave Raye a lifelong calling of entertaining and serving the nation’s service personnel in the field. Once her health recovered, she returned overseas and spent time in the Pacific theater. When the Berlin Airlift began in 1948, Raye flew to Germany to put on performances for soldiers and airmen. With the outbreak of war in Korea in 1950, she joined her USO colleagues to visit the United Nations forces and made her way to the front lines to mingle with the soldiers and marines, both those in the cold and mud and the wounded on their way to hospitals in the rear.

The war in Vietnam would prove the apex of Raye’s involvement with the USO and the entertainment of American military personnel overseas. Between 1965 and 1972, Raye spent an average of four months each year in Vietnam and participated in no fewer than eight USO tours. Where many USO personnel stayed in the major cities and base camps, Raye—either by herself or with a single accompanist—ventured out to the frontlines and to small Special Forces camps and isolated outposts in South Vietnam. Wearing combat boots and standard issue uniform fatigues, she would hitch a ride in a helicopter or jeep to perform in front of audiences of every size, play cards with the men, share drinks and rations, and offer a bit of home to anyone she met. Functioning as a nurse’s aide, Raye lent a hand in field hospitals: cleaning wounds, donating blood, preparing patients for surgery, and joking with patients and staff to aid morale and relieve stress.

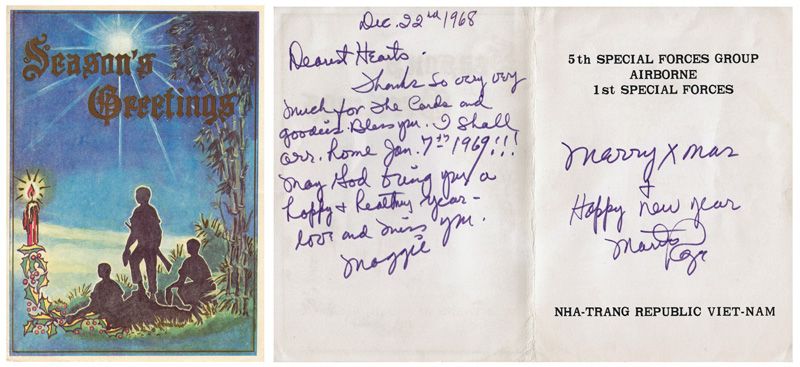

Raye ingratiated herself to the soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines who she encountered in her travels. The Fifth Special Forces Group (Airborne) made her an honorary Green Beret and she wore the famed headgear with pride. The marines made Raye an honorary colonel. The army made her an honorary lieutenant colonel, a rank she wore on her fatigue uniform in the field. “Colonel Maggie” or “Maggie of the Boondocks” would answer hundreds of letters from military admirers and would take phone numbers home with her so that she could call wives and parents of service members to tell them how their sons and husbands were doing far from home.

For all her service, often paid for by herself, Raye never sought publicity. Her involvement was deeply personal and patriotic. In a rare interview Raye said simply that “[e]nough people are going against the troops. It isn’t their fault that they’re there. They should be helped.” What few stories covered her work titled her a “quiet humanitarian.”

But Raye’s contributions did not go unnoticed. In a certificate of appreciation to Raye, General William Westmoreland, commander, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, wrote that “[b]ecause of your personal desire to present your show for the men at the more remote locations, these men serving under hardship conditions have had the rare pleasure of seeing and talking to a personality who is loved and respected by all and needs an introduction to none.” In 1969, Raye became the first woman to receive the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award on behalf of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Presenter and friend Bob Hope remarked how Raye “earned the love, respect and undying admiration of every homesick kid in uniform who so desperately seeks a touch, a feel, a moment of home.”

When American involvement in the Vietnam War concluded, Raye’s connection to the nation’s veterans remained strong. Beginning in 1986, the “Medals for Maggie” campaign coordinated with other veterans’ organizations to petition Congress and the President to award Raye the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, for service to veterans in three wars. Overtures to Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush proved unsuccessful, but after a submission of 40,000 veteran signatures, President Bill Clinton awarded Raye the medal on November 2, 1993. Because Colonel Raye was too ill to receive the medal in the White House, retired Special Forces Master Sergeant and Medal of Honor recipient Roy Benavidez pinned the medal on her chest at her home in Bel-Air, California, declaring her “the Mother Teresa of the armed forces.”

One final recognition would be bestowed upon Raye. At her death on October 19, 1994, the U.S. Army granted Raye’s request to be buried in the military cemetery at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, the first civilian woman ever so honored. With an honor guard of Green Berets present, Raye’s flag-draped coffin was laid to rest alongside “her boys,” forever linked in death as in life.

Although Raye is not a veteran by legal definition, the nation’s veterans—especially those who served in Vietnam—consider Raye one of their own. America’s veterans led the effort to honor her in grateful recognition for all she selflessly did to support them overseas. As the veterans remembered her service and sacrifice, may we all in turn take time today to honor and thank our veterans at home and abroad who have given selflessly of themselves for the betterment of our nation.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on November 9, 2021. Read the original version here.