NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

The Workers’ Turkey

Like many homes across America, in my home Thanksgiving meant turkey. Lots of turkeys. And employers gave out these big birds as work incentives, to ensure that their working-class employees wouldn’t go without this crown jewel on their table.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ba/53/ba53b674-af8d-4160-9220-17b7b6c981ff/kids_eating_circa_1982_loza.jpg)

Like many homes across America, in my home Thanksgiving meant turkey. Lots of turkeys. Five or six turkeys. The day before Thanksgiving, my aunt Rosalba's small kitchen was filled with turkeys. Two battled for the limited surface space on the kitchen table and the others took the chairs.

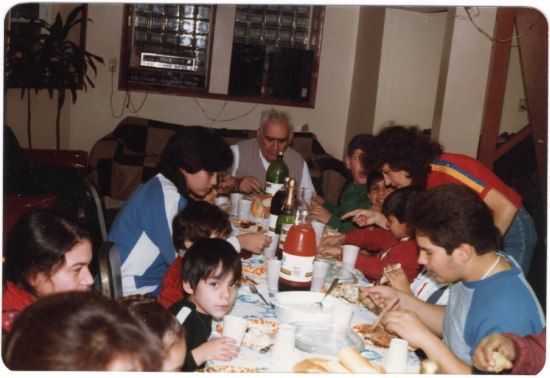

My extended family occupied every room in a three-apartment brownstone in Chicago, and my aunt's apartment was home base. While every other adult worked long days outside of the home, my aunt worked even longer days taking care of all of the kids. She would take all six of us to school, pick us up, and make dinner for everyone. All of the kids would gather around the small table and eat dinner at 4:00 p.m. in what we called "first shift." Since the table didn't have enough chairs for all the kids, my aunt would push two chairs together and sit three of us there. Then the first group of adults would arrive after 5:00 p.m., and usually there was a third shift around 7:00 p.m. Aunt Rosalba made dinners that could feed about 15 people every day. The holidays were no exception.

For Thanksgiving, she needed all hands on deck. On a shoestring budget, Aunt Rosalba would gather all of the ingredients: cans of corn, powdered mashed potato mix, a tub of margarine, nopales, tomatillos, onions, cilantro, jalapeños, tortillas, and French bread. I helped by opening cans and mixing hot water into the instant potato mix. She made green salsa and a salad out of nopales. Then came the star of the show: the turkeys.

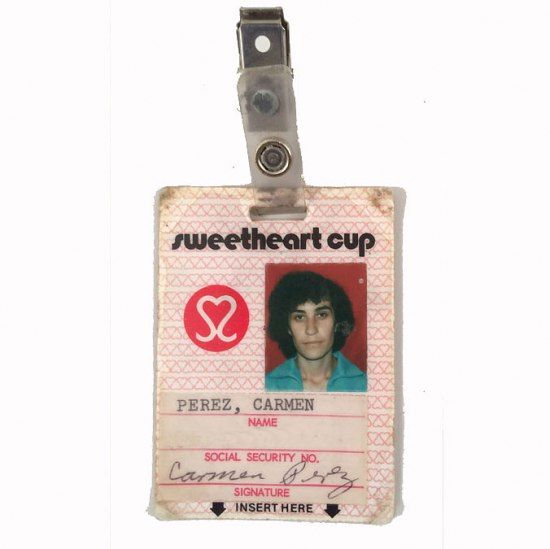

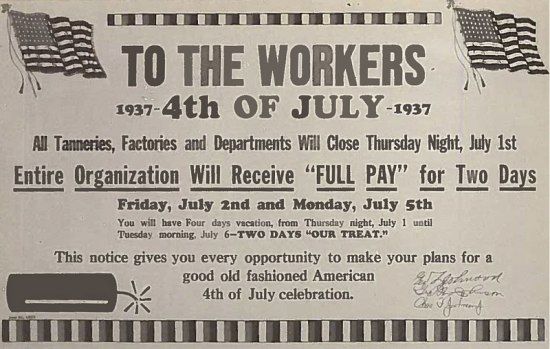

The night before Thanksgiving, most of the adults would drop off the turkey they received from work. Employers gave their workers these big birds as work incentives, a sign of their appreciation, and to ensure that their working-class employees wouldn't go without this crown jewel on their table.

With jobs in factories, construction, and warehouses, every single adult in my family was either working class or perhaps even working poor. They all came from Mexico "para trabajar"—to work. They worked as much as they could, and despite the exhaustion they welcomed the overtime, hoping they would see bigger paychecks. Despite all of this work, I became very skeptical of labels like "hard workers." They were so much more than their work, and that characterization seemed to obscure the fact that they had to labor longer hours in order to cover basic necessities.

For my family, the meaning of Thanksgiving wasn't tied to honoring the Pilgrims. They celebrated the fact that they had a day off and that we all had a special opportunity to eat together. We would bring out giant folding tables and rusty folding chairs from the basement so we could sit together. As the years passed and my aunt invited more family and friends, the tables were set up in the basement. The turkeys not only helped us celebrate Thanksgiving: my aunt would put two away for mole on New Year's. Then, of course, there were the hams that employers handed out for Christmas. Christmas meant thick slices of ham, shaped by the cans they came in, flanked by plates of tamales. But the turkeys always bookended the holiday season. Their return on New Year's in the thick chocolaty spicy mole was welcomed.

I can't remember exactly when the workers' turkeys dwindled, but somehow by the time I was a teenager in the mid-90s, many employers stopped giving out Thanksgiving turkeys. At first, instead of a turkey, some of the adults would bring home gift certificates, bright green pieces of paper we could use to pick up a turkey at the grocery store. Then the employers just stopped giving out anything. The turkeys weren't the only thing that changed. Some family members also went from having a paid day off for Thanksgiving, to half a day. Some had to start taking a vacation day to join us at dinner.

Although the bottom economic line swayed their employers to do away with the turkey, the ham, and the compensated holiday, the workers I knew still felt lucky that they had jobs. They felt lucky—not because they enjoyed the long hours and arduous labor, or because they loved their jobs—but because they understood that as workers they stood on very precarious grounds. Something had changed and they felt it.

My family still celebrates Thanksgiving together. Now we sit around several even longer folding tables and before we eat dinner everyone says one thing they are thankful for. The words that ring loudest and repeatedly are always, "familia, salud, y trabajo,"—family, health, and (of course) work.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on November 17, 2017. Read the original version here.