NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

Illustrating the Teddy Roosevelt Africa Expedition

In 1909, President Teddy Roosevelt decided to travel to Africa with naturalists to collect specimens for the Smithsonian

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e9/54/e9544858-4c73-4f92-a4ff-2510620b2e32/ga12195_east_african_express_ed.jpg)

The Roosevelt-Smithsonian collecting expedition to Africa between 1909 and 1910 was the idea of the president during the last year of his administration. Roosevelt was interested in working with the Smithsonian, serving both his own and the institution’s interests by participating in a hunting and scientific collecting expedition. Roosevelt wrote to Smithsonian Secretary Charles Doolittle Walcott on June 20, 1908, reporting his itinerary for the African expedition and the idea that he wanted to travel with field naturalists to prepare the specimens:

“I shall land in Mombasa [Kenya] and spend the next few months hunting and traveling in British [East Africa, Kenya] and German East Africa [Burundi, Rwanda, and Tanzania]; probably going thence to or toward Uganda, with the expectation of striking the Nile about the beginning of the new year, and then working down it, with side trips after animals and birds. . . . I am not in the least a game butcher. I like to do a certain amount of hunting, but my real and main interest is the interest of a faunal naturalist. . . . I would like . . . to get one or two professional field taxidermists, field naturalists, to go with me, who should prepare and send back the specimens we collect.”

Roosevelt’s expedition team included three field naturalists who were responsible for both large and small mammals and birds. After the completion of the expedition, the final number of collections received by the Smithsonian totaled roughly 6,000 mammals, 11,600 other specimens, including birds, and 10,000 plant specimens.

What was the connection between Berryman and Roosevelt? Like many editorial cartoonists Berryman’s job was to cast the events of the day in a humorous light. His cartoon subject matter regularly included political figures and settings. His distinguished career gave him a following and the opportunity to influence the public. For example, Berryman’s cartoon “Remember the Maine” was associated with the American battle cry of the Spanish-American War. His Pulitzer Prize-winning World War II cartoon titled “…Where is the Boat Going?” lampooned decisions about the location needs of the U.S. Navy and its ship, the USS Mississippi. Berryman also contributed to American toy culture with his 1902 cartoon showing President “Teddy” Roosevelt and a bear cub, which is believed to have inspired the toy, the teddy bear.

Berryman’s artistic style changed little over his career. His pen and ink depictions of political figures and settings is distinct. By 1949, the year of his death, Berryman had become so well known, especially in Washington circles, that then President Harry Truman is quoted as having said, “You (Berryman) are a Washington Institution comparable to the Monument.”

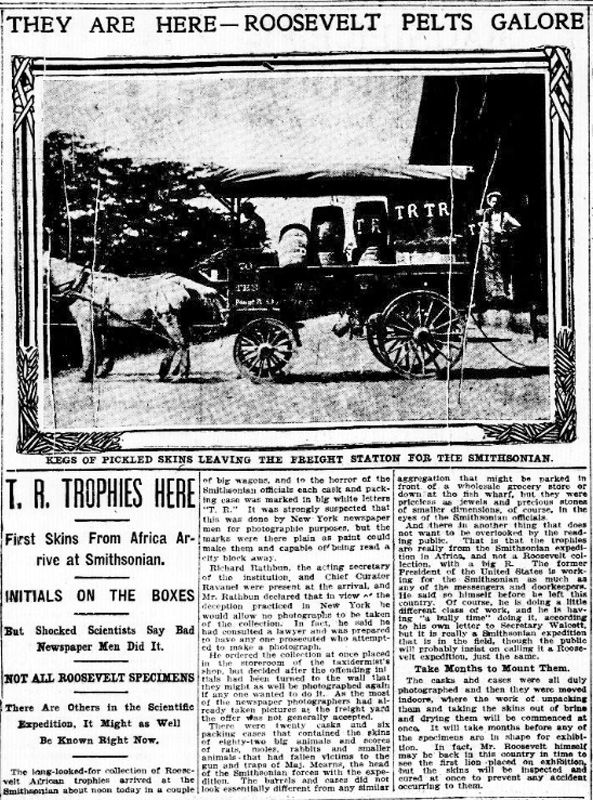

The “East Africa Express” drawing was published on the front page of the August 25 issue of The Washington Star, but no other reference was made to it in that issue. The earlier August 24 issue of the paper, however, included an article about the collection coming to town, and commented on the unappreciated “TR” markings on the crates.

“The long-looked-for collection of Roosevelt African trophies arrived at the Smithsonian about noon today in a couple of big wagons, and to the horror of the Smithsonian officials each cask and packing case was marked in big white letters ‘T. R.’ It was strongly suspected that this was done by New York newspaper men for photographic purposes, but the marks were there plain as paint could make them and capable of being read a city block away.”

Sometime after the August 23, 1909, publication in The Evening Star, the drawing was given by the artist to Richard Rathbun (Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian in charge of the United States National Museum). It was later distributed to the Graphic Arts unit in 1921 by William deC. Ravenel, the administrative assistant to Rathbun. By the time of this transaction, long after the novelty surrounding the arrival of the specimens, the work was given a permanent Smithsonian home.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on August 24, 2021. Read the original version here.