NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

The ‘Green Book’ Became an Atlas of Self-Reliance for Black Motorists

For black Americans, the central paradox of the American automobile age was that it occurred in the middle of the Jim Crow era

:focal(375x307:376x308)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/54/3b/543b926e-2f27-47e4-a5c3-e11d71770247/convertible.jpg)

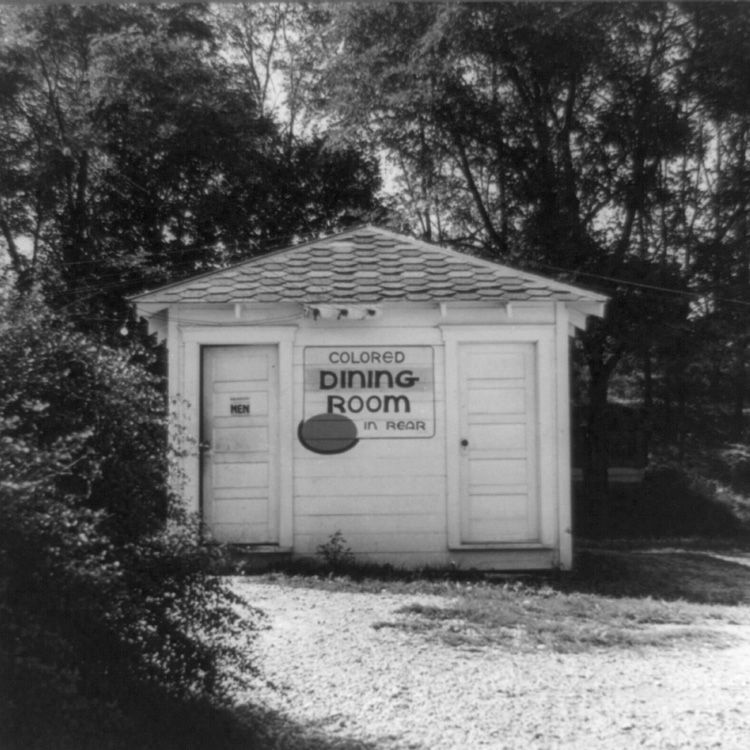

However, once they pulled off the interstate, the freedom of the open road proved illusory. Jim Crow still prohibited black travelers from pulling into a roadside motel and getting rooms for the night. Black families on vacation had to be ready for any circumstance should they be denied lodging or a meal in a restaurant. They stuffed the trunks of their automobiles with food, blankets and pillows, even an old coffee can for those times when black motorists were denied the use of a bathroom.

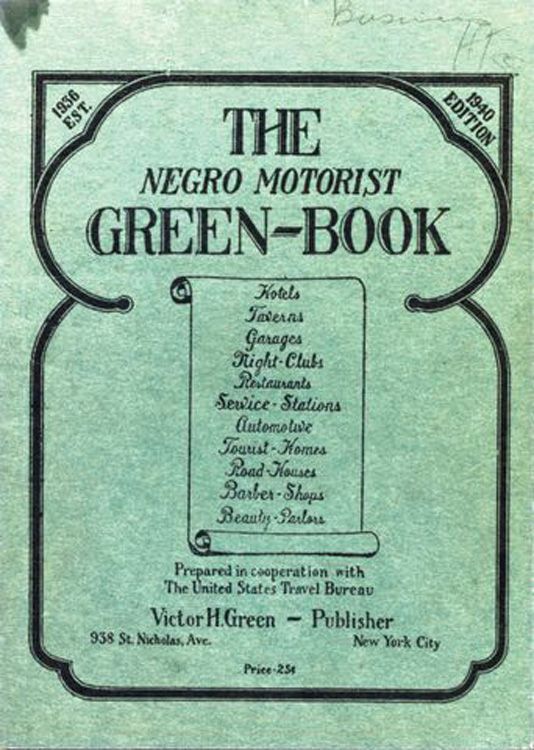

To avoid these dangers, the Negro Motorist's Green Book offered to help black motorists travel safely across a landscape partitioned by segregation and scarred by lynching. Published in Harlem by Victor and Alma Green, it came out annually from 1937-1964. While the Green Book printed articles about auto maintenance and profiled various American cities, at its heart was the list of accommodations that black travelers could use on their trips. Organized by state, each edition listed service stations, hotels, restaurants, beauty parlors, and other businesses that did not discriminate on the basis of race. In a 2010 interview with the New York Times, Lonnie Bunch, director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, described this feature of the Green Book as "a tool" that "allowed families to protect their children, to help them ward off those horrible points at which they might be thrown out or not permitted to sit somewhere."

The inaugural edition of the guide ran 16 pages long and focused on tourist areas in and around New York City. By the eve of U.S. entry in World War II, it had expanded to 48 pages and covered nearly every state in the union. Two decades later, the guide was nearly 100 pages long and offered advice for black tourists visiting Canada, Mexico, Europe, Latin America, Africa, and the Caribbean. As historian Gretchen Sorin describes, under a distribution agreement with Standard Oil, Esso service stations sold two million copies annually by 1962.

The vast majority of the businesses listed in the Green Book were owned by black entrepreneurs. By gathering these institutions under one cover, Victor and Alma Green mapped out the economic infrastructure of black America. Thus, the Green Book was more than a travel guide; it also described two 20th-century African American geographies.

At first glance, the Green Book maps the territorial limits of African American freedom. The America that black people lived in under Jim Crow was much smaller than the one in which white Americans lived. After World War II, Americans took their cars on the newly built interstate system and invented the road trip. But this open road wasn't open to everyone. When Disneyland opened its gates in 1955, the path to the Magic Kingdom was fraught with dangers for most black travelers, compelled to chart their journey from one oasis of freedom to the next using the Green Book as their guide.

However, the Green Book was also an atlas of black self-reliance. Each motel, auto repair shop, and gas station was a monument to black determination to succeed in a Jim Crow nation. Before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, these businesses represented a source of black economic power that could be used to build a more just America. A number of these black business leaders would join the NAACP and other civil rights organizations in order to translate their economic power into political power and use that to help bring an end to Jim Crow. They used their money to bail protestors out of jail, fund the operations of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, and pay for the buses that sent thousands to the 1963 March on Washington.

Even though the Green Book was never meant to be an explicitly political document, it described the economic infrastructure of the black freedom struggle. Indeed, Victor and Alma Green articulated this hope in the 1948 edition:

"There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment."

More information about the Negro Motorists' Green Book:

- The New York Public Library has digitized the Green Book from 1937-1962. You can browse these editions on their website.

- Mapping the Green Book is a project unearthing the histories of locations cited in the guide.

- The University of South Carolina has an interactive Google Map created using the 1956 Green Book.

- In 2010, NPR interviewed civil rights leader Julian Bond about his childhood memories of using the Green Book

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on July 30, 2015. Read the original version here.