NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

How Madam C.J. Walker Changed Philanthropy

Walker challenged the accumulation-of-wealth model of philanthropy, which postpones giving until the twilight years of life

:focal(265x197:266x198)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/80/43/8043a72b-94c1-4357-b0d0-1eec5f682ea7/madam_cj_walker.jpeg)

What sort of causes and institutions did Madam C. J. Walker support and why?

Before she became famous, Sarah Breedlove, aka Madam C. J. Walker, was an orphan, child laborer, teenaged wife and mother, young widow, and homeless migrant. She knew firsthand the struggles of being poor, black, and female in the emerging Jim Crow South. Her philanthropic giving was focused on racial uplift, which meant helping African Americans overcome Jim Crow and achieve full citizenship. She gave money to local, regional, national, and international organizations that were typically founded by or focused on serving African Americans.

Her racial-uplift giving was primarily directed toward black education and social services. She gave to black colleges and secondary schools like Booker T. Washington's Tuskegee Institute, the Palmer Memorial Institute in North Carolina, and the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute in Florida, because Jim Crow laws denied her an education during her childhood in Louisiana and Mississippi.

For social services, she gave to organizations such as the Flanner Settlement House in Indianapolis, the Alpha Home elder-care facility in Indianapolis, the St. Louis Colored Orphans' Home, the St. Paul's AME Mite Missionary Society in St. Louis, and to the international and colored branches of the YMCA. These organizations were on the ground responding to the basic needs of African Americans related to discrimination, food, healthcare, housing, daycare, and community development.

Some of these organizations, and others she supported, were run by women leaders, like Mary McLeod Bethune and Charlotte Hawkins Brown—which was important to Walker, too, as they were fellow race women and friends. To help the NAACP fight lynching, Walker also made important direct and estate gifts, which the organization later credited with helping it to survive the Great Depression.

How did her business practices inform her philanthropy?

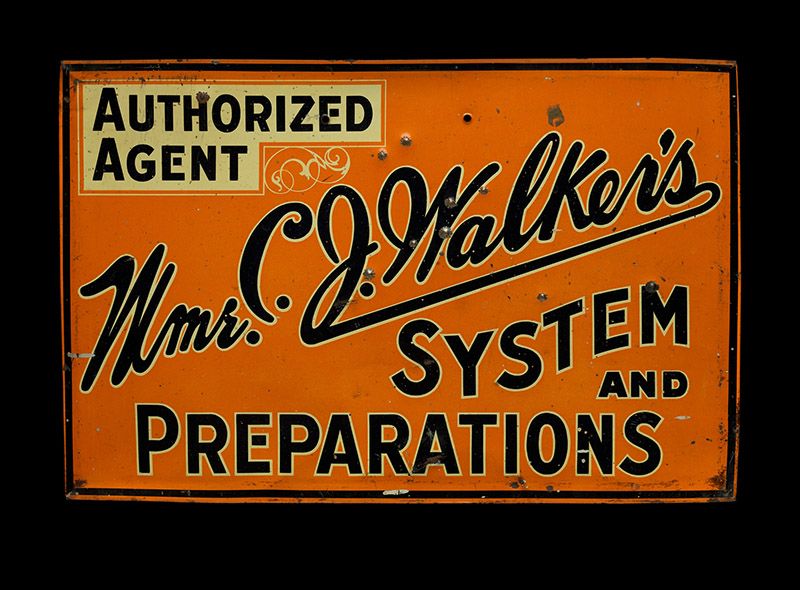

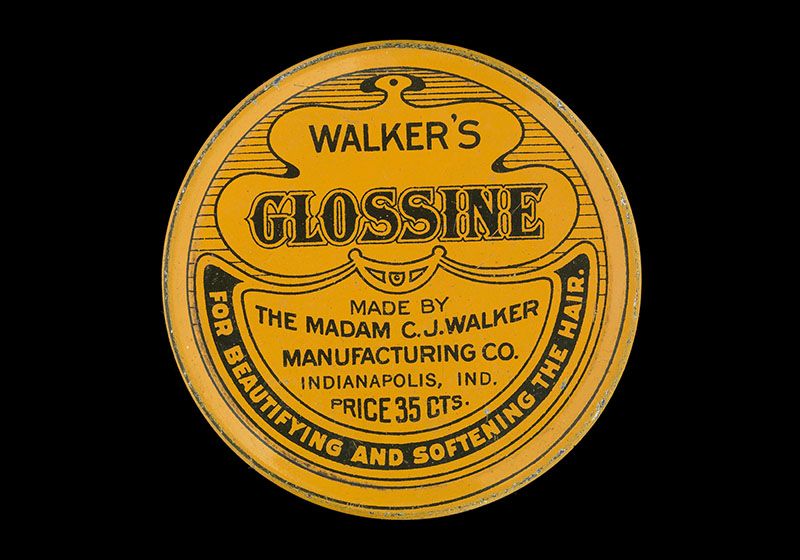

Walker's attorney and confidante, Freeman B. Ransom, called the Walker Company a "race company," which meant it was founded by African Americans for the betterment of their own community as they fought against racial discrimination. This orientation framed both the commercial and philanthropic purposes of the company. Through this lens, employment as a Walker agent created a philanthropic opportunity for thousands of black women to support themselves, their families, and communities in spite of Jim Crow's restrictive laws and customs that deliberately locked them out of labor markets. Additionally, education was an important philanthropic goal of African Americans given severe limitations on their learning under Jim Crow. The Walker network of beauty schools provided education and a career path for black women toward credentialization and gainful employment in the respectable profession of beauty culture. In this way, the opportunity to become educated was a gift that enabled thousands of graduates around the country to improve themselves.

What can Madam C. J. Walker's experience tell us about the history of American philanthropy?

Madam C. J. Walker's experience grew out of black women's historical experience of America. She represents black women's daily ways of giving in their communities to survive in America, and to express and preserve their dignity and humanity. She is an important historical marker of the long-standing and deep-rootedness of African American philanthropy—it is not new and emerging. It predated Walker, and it vibrantly continues to this day. While she was a contemporary of the white philanthropists who often dominate our historical understanding of early-20th-century American philanthropy, she presented a different and much more accessible way to do philanthropy, regardless of one's station in life. She challenged the accumulation-of-wealth model of philanthropy, which postpones giving until the twilight years of life. She demonstrated that anyone can give and be a donor with whatever resources—monetary and nonmonetary—they happen to have at the time need is observed, and that as one's resources increase, so should one's giving.

To learn more about Madam CJ Walker and other inspiring Black philanthropists, check out this free virtual event on February 10, Who Counts as a Philanthropist? A Conversation About Black Philanthropy. From Richard Allen, the formerly enslaved founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, to Madame C.J. Walker, museum curators and guest historians will introduce and discuss historically overlooked philanthropic contributions of African Americans. Drawing on groundbreaking scholarship by Tanisha C. Ford, Ph.D. and Tyrone McKinley Freeman, Ph.D. in discussion with Curators Amanda B. Moniz, Ph.D., and Modupe Labode, Ph.D., the program will examine the intertwined history of philanthropy, business, and social justice. The program will also feature a Q&A with the audience.

The Philanthropy Initiative is made possible by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and David M. Rubenstein, with additional support by the Fidelity Charitable Trustees' Initiative, a grantmaking program of Fidelity Charitable.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on March 27, 2018. Read the original version here.