NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

Why a Social Activist Opposed Woman Suffrage

The right to vote, insisted some women, would undermine their efforts to promote the public good

:focal(498x293:499x294)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1d/2d/1d2dd9fc-96d3-46db-95fa-67155bcb56fd/nmah-jn2019-02103-000001_anti-suffrage.jpg)

The trouble began soon after well-known social reformer Emily Bissell had finished her remarks at the meeting of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage’s Washington, D.C., branch. As audience members got ready to leave that March 1912 evening, supporters of woman suffrage stationed themselves at the doorway to press pro-suffrage materials. The conflict grew heated with insults “hurled back and forth,” according to a newspaper report, until eventually the fracas between the “Pros” and “Antis” subsided.

Bissell, a leader in the Anti camp, believed deeply in women’s role in public affairs—she opposed woman suffrage in part because she believed it would get in the way of women’s philanthropy. She and many other women in the early 1900s were making their mark by initiating and running charitable programs, by fundraising and volunteering for all manner of causes, and by lobbying legislators and other male leaders for policies and spending they favored. The right to vote, Bissell insisted, would undermine their efforts to promote the public good. Bissell also opposed women’s suffrage for several reasons including racist opposition to the possibility of African American women voting.

The philanthropy of Emily Bissell

Born into a prominent Wilmington, Delaware, family, Bissell began what became a career in social activism in the 1880s, when she was in her early 20s. Industrial expansion and urban growth were then reshaping Wilmington, with harmful effects for many working-class Americans. When a pond used for swimming and ice skating in Wilmington’s Forty Acres neighborhood was destroyed to build a railroad, Bissell and other members of her church became concerned about the lack of recreational opportunities and, as she saw it, the disruptive behavior of neighborhood boys that would follow. Bissell led fellow church members in establishing an athletic club to benefit and discipline the young working-class men. Opened in 1883, the West End Athletic Club changed over time to become a place where middle-class reformers, especially women, sought to meet the needs of under-resourced local residents. Bissell and her colleagues brought many of the era’s social experiments, including a kindergarten, a playground, and a well-baby clinic, to the settlement house. For decades, Bissell led the institution, particularly in her role as a formidable fundraiser.

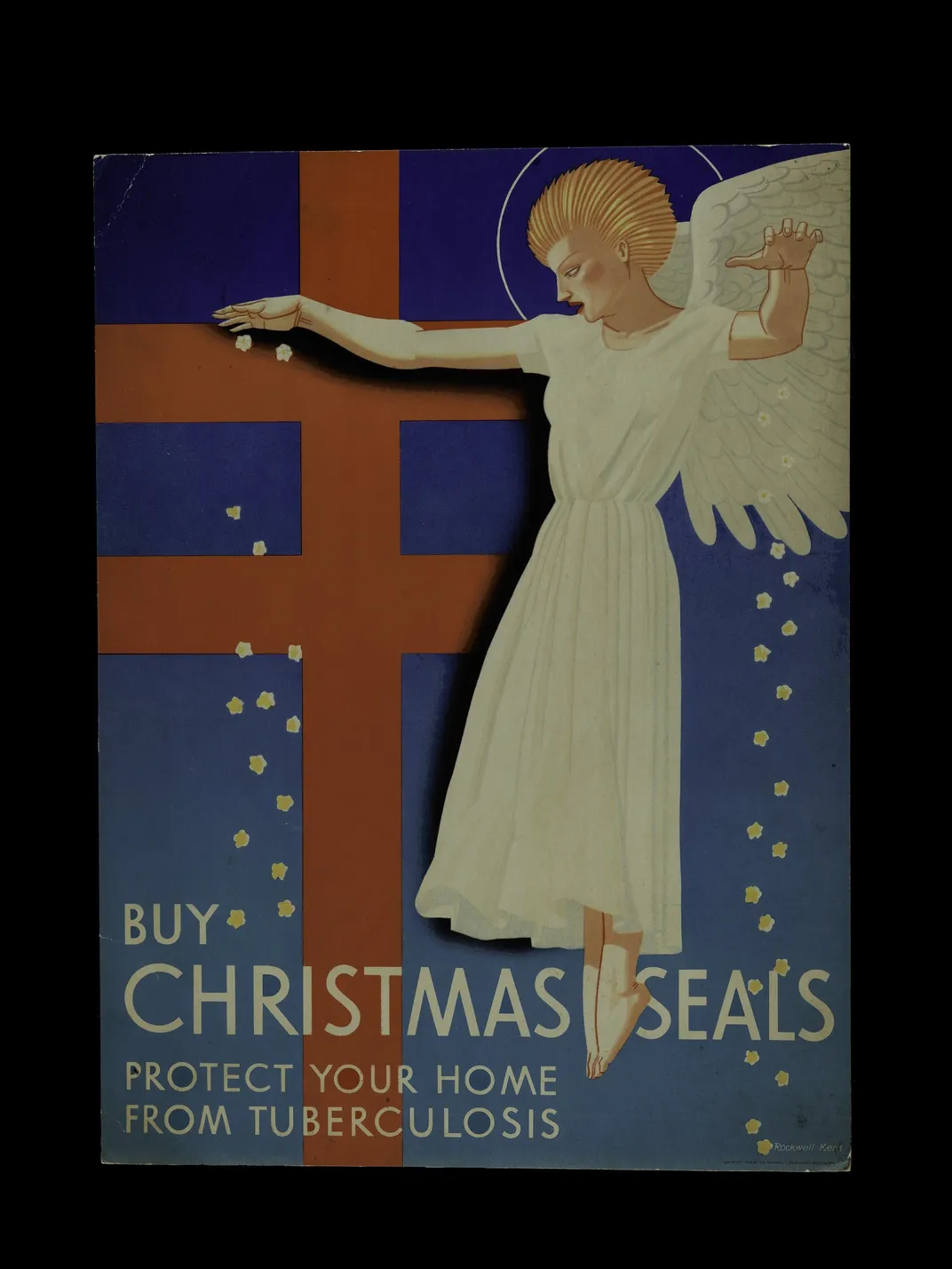

Although she honed her fundraising skills with the settlement house, Bissell is best known for launching the annual Christmas Seals fundraiser for the anti-tuberculosis cause. Tuberculosis killed thousands of Americans yearly until the development of antibiotics in the mid-1900s. In the early 1900s, public health officials and philanthropic groups combated the disease with various measures The Delaware Anti-Tuberculosis Society had built a sanatorium where TB patients could rest and recover, but before long funds were running low. Bissell remembered reading an article by the Danish-born American social reformer Jacob Riis about how Christmas seals were used in Denmark to raise money to combat TB. Inspired by the idea, she won support from the American Red Cross, found a printer to design the seals, persuaded women friends to place initial orders, navigated obstacles about where they could be sold, and ignored the ad men who expected the whole effort to fail. Bissell proved right. Many bought the decorative seals to affix to Christmastime mail and, thanks to her savvy courting of positive publicity, the effort became a mass philanthropy phenomenon. About a decade later, that experience helped shape mass fundraising efforts during World War I.

The philanthropy of women in the era

Bissell stood out for her leadership, but was typical of women in the era in turning to philanthropy as a realm to debate and set priorities for local, national, and international communities. In Bissell’s day, women gave their time and money to diverse causes, with many supporting religious charities, social welfare organizations, and temperance (as Bissell did). Black women donated to support fellow African Americans, who faced limitations on their opportunities in a racist society. Some women gave to women’s suffrage and other feminist causes. Women complemented their giving by also advocating before lawmakers on behalf of legislation they favored, as Bissell did for causes including the fight against tuberculosis, the regulation of child labor, and anti-suffrage.

Bissell’s case against woman suffrage

Bissell looked at this landscape and saw women exercising influence in society in ways she believed appropriate to their gender. Women contributed to society, she thought, by raising the next generation of citizens. The vote would take time away from mothering. Moreover, women suffragists, she claimed, upended proper femininity by wearing short hair and bloomers. Worse, in her racist view, African American women would gain the right to vote and be able to shape policies that affected well-off white women.

Key to her opposition to women’s suffrage, however, was that she thought the vote would undermine women’s influence on public life. (Implicitly she meant white women’s influence.) Setting priorities about the regulation of society and the allocation and distribution of resources are the heart of politics. Yet Bissell and her colleagues saw their activities–including their lobbying–as nonpartisan. Their effectiveness, they believed, came from their separation from formal politics. “We were powerful,” Bissell said, “because we had no political entanglements.”

Bissell lost the argument on suffrage. Yet her view prevailed that women should play an active role in public life. Like the women who funded women’s suffrage, she believed women should use their financial and organizational clout to advance their visions for society. Whether for or against women’s right to vote, their philanthropy was politics by another name.

The Philanthropy Initiative is made possible by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and David M. Rubenstein, with additional support by the Fidelity Charitable Trustees' Initiative, a grantmaking program of Fidelity Charitable.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on April 15, 2020. Read the original version here.