NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

How Did a 17th-Century French Sundial End Up Buried in a Field in Indiana?

Curator Peggy Kidwell solves the mystery of a pocket sundial from the 1600s

:focal(400x259:401x260)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b1/99/b199aee8-5fe8-4dc2-83ef-b6e96e35ba6e/ma325565_nmah-rws2022-00083_side.jpg)

First, a bit of background on sundials. From ancient times, people have used changes in the lengths and directions of shadows cast by objects in the sun as a measure of time. Sundials date at least to around 1500 BCE. Early examples were made in Egypt, Babylon, and China. They came to be found in public squares, on the walls of churches, in gardens of the well-to-do, and in observatories. The length of the day varied with the latitude of a location and the time of year, while the hour depended on the local longitude—time zones embracing a range of longitudes would not be introduced until the late 1800s.

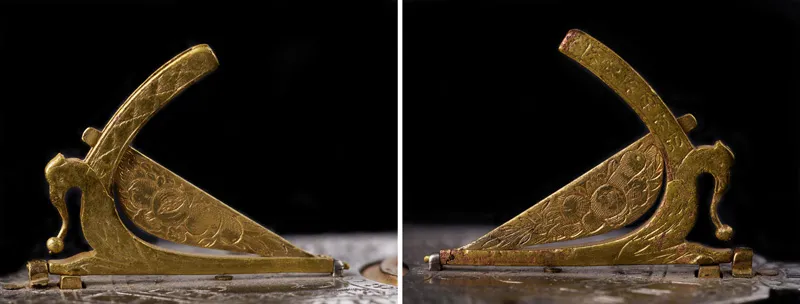

Portable sundials date to antiquity, and by the 1600s, a few Europeans carried sundials that fit in the pocket. Some of these dials, like the one above, had a shadow-casting component (called the gnomon) that could be adjusted according to the latitude of the observer. Each latitude required a different hour scale because the sun would be at a different angle higher or lower in the sky at each location at noon or any other given hour. The French pocket sundial shown here has three hours scales and a gnomon whose angle can be adjusted from 30 to 55 degrees. This meant it would have worked not only in Europe but across the range of French territory in North America.

The dial itself offers clues about its origins. The inscription “Bourgaud Nantes” informs us that it was made in the workshop of a clockmaker, Bourgaud, in Nantes, France. The dial’s gnomon has a support in the shape of a bird, with a tiny plumb bob (a hanging weight used to establish a vertical line). A magnetic compass is used to align the sundial. Around the outside rim of the compass, eight directions are engraved in (slightly abbreviated) French: Nord, Nouest, Ouest, Souest, and so forth. Inside the compass bowl, these directions have been roughly labeled with English abbreviations: N, NW, W, SW, and so forth. The French and English labels do not presently line up. Moreover, the compass has a six-pointed star, not the usual eight-pointed compass rose. The compass bowl and the magnetic needle are later replacements.

Colonists did not make such instruments; they imported them from Europe. Similar devices (now preserved in other museum collections) were discovered in excavations on the site of battlefields, forts, trading posts, and settlements, particularly in New France: French-held territory from what is now Canada down to the Gulf of Mexico. In her research on sundials in the American colonies, Schechner has drawn attention to several of these dials, and notes that some 18th-century French sundial makers, like Pierre le Maire (and his son of the same name), made pocket dials that carefully listed the latitude of places of French interest in both North and South America.

During the 1700s, the French occupied much of what is now the state of Indiana, trading with Native inhabitants and establishing outposts with French names like Terre Haute. The French ceded the territory to the British in 1763 at the end of the French and Indian War, but British settlers were excluded from the area. Near the end of the American Revolution, the British passed the territory to the newly established United States, which included the land in the Northwest Territory. In 1800 the Indiana Territory was divided from the Northwest Territory, and over the next thirty-odd years, Native Americans were expelled from the land through a series of treaties. The state of Indiana was admitted to the Union in 1816, and within eight years a settlement was laid out in a new town named Montezuma near Terre Haute. How the Bourgaud pocket sundial came to be in Indiana we have no idea, but if the story of its discovery is accurate, then the dial could have arrived in a field at any point during a vast swathe of time.

Fortunately, we know a little bit more about the sundial’s purported discoverer, Dr. Elisia Cannon. In 1840 Horace Cannon, a Quaker physician in North Carolina, and his wife, Gulielma, decided that living in a state where African Americans were legally enslaved was intolerable. They and their children moved to Montezuma, Indiana. Dr. Cannon’s son Elisha B. Cannon also decided to take up medicine. By 1860 the younger Cannon was married and living on his own property in Montezuma. It was here that Cannon allegedly plowed up the sundial that is now part of the Smithsonian's collections.

Elisha Cannon and his brother Joseph Cannon eventually moved to Illinois. There, Joseph Cannon became a lawyer, met the young Abraham Lincoln, and took up a career in politics. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and rose to become Speaker of the House; the Cannon House Office Building on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., is named for him. Elisha Cannon had a quieter career, participating in several local medical societies.

In the 1960s, after both men were long dead, the pocket dial was purchased by the Smithsonian’s Museum of History and Technology (what is now the National Museum of American History). It was and is an elegant and noteworthy European timekeeping device. Both recent research on sundials and the genealogical sources now readily available online make it possible to learn something of the history of the device in the United States.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on July 20, 2022. Read the original version here.