NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

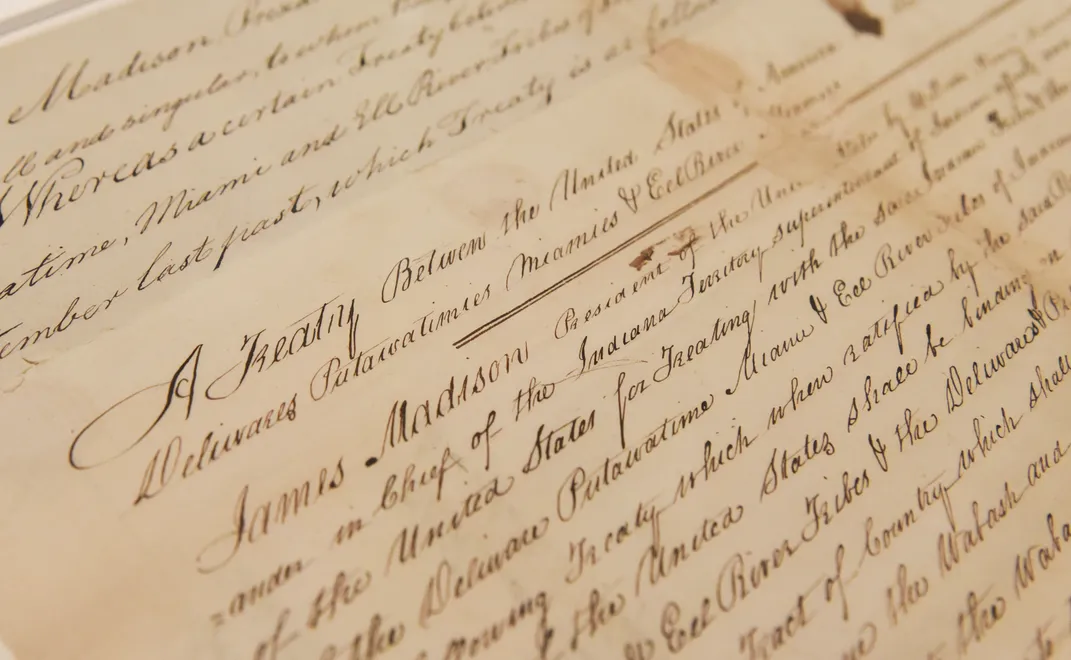

The Treaty of Fort Wayne, 1809—a treaty that led to war—goes on exhibit

In 1809, nearly 1,400 Potawatomi, Delaware, Miami, and Eel River Indians and their allies witnessed the Treaty of Fort Wayne, ceding 2.5 million acres of tribal lands in present-day Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio in exchange for a peace that did not last. This September, representatives of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi saw the treaty go on view at the National Museum of the American Indian. “It is an honor to come full circle to an article that our ancestors signed,” Tribal Chairman John P. Warren said. “I hope we are fulfilling their hopes and dreams by being here.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Pokagon_Band_in_Collections.png)

“It is an honor to come full circle to an article that our ancestors signed. I hope we are fulfilling their hopes and dreams by being here.” —Chairman John P. Warren, Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians

On September 19, 2017, leadership of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, the National Museum of the American Indian, and representatives of the National Archives came together at the museum in Washington, D.C., for the unveiling of the Treaty of Fort Wayne of 1809. This unveiling marked the seventh rotation of treaties to be installed the exhibition Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations. At the ceremony, Director Kevin Gover noted that the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians has been a tremendous partner with the National Museum of the American Indian. James Zeender, senior registrar in the Exhibits Division of the National Archives, described the importance of these original documents: “Treaties are the supreme law of the land. There are 370 Native treaties at the National Archives stored next to treaties with other sovereign nations.” The National Archives has collaborated with the museum to display a series of historic treaties in the exhibition.

In early autumn 1809, 1,379 Potawatomi, Delaware, Miami, and Eel River tribal members and their allies gathered to witness the signing of the Treaty of Fort Wayne. On September 30, 24 “Sachems, Head men, and Warriors” put their X next to their names. William Henry Harrison, governor of the Territory of Indiana, led a U.S. delegation of 14 representatives. The agreement called for the four tribes to cede 2.5 million acres of their lands in present-day Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio in exchange for what amounted to two cents an acre. President James Madison ratified the treaty with the consent of the United States Senate on January 2, 1810; a presidential proclamation dated January 16 required “all officeholders and citizens ‘faithfully to observe and fulfil’ the treaty.”

The Treaty of Fort Wayne led to the end of the peace that had prevailed since 1795 between the Ohio Valley Nations and the United States. As Native lands decreased through the westward expansion of the United States, resistance grew under the leadership of Tenkswatawa, the Shawnee Prophet, and his brother Tecumseh, the famous war chief. Not all the tribes in the region were agreeable to the signing. Individual members of the Miami objected, saying it was time to “put a stop to the encroachment of the whites.” Governor Harrison pressured them to rely on treaty-making. “Treaties made by the United States with Indian Tribes [are] considered as binding as those which [are] made with the most powerful Kings on the other side of the Big Water,” Harrison said. Eventually the Miami conceded. Within two years, Governor Harrison let an attack on Prophetstown, the camp of Tenkswatawa and his followers on the Tippecanoe River. The battle at Tippecanoe set off a new war.

By 1846 most of the Native Nations that signed the Treaty of Fort Wayne had been removed west of the Mississippi. The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians was an exception. The Treaty of Chicago of 1833 secured the right of the tribe to purchase land and remain in Michigan. The people took the name of the leader who negotiated that agreement, Leopold Pokagon (ca. 1775–1841).

In 1994—185 years after the Treaty of Fort Wayne, almost to the day—the U.S. government, through congressional legislation, restored all rights to the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi as a federally recognized tribe. “This Thursday [September 21] marks the anniversary when our tribe was here in Washington, D.C., to be reinstated [as a federally recognized tribe],” Pokagon Elders Council Member Judy Winchester said at the treaty installation. “We are leaving Washington tomorrow so that we can be home to celebrate with our tribal members the reinstatement of our tribe.”

“Treaties are the supreme law of the land.” Thinking about that statement after the ceremony, I wondered if other American Indians believe the United States has fulfilled its promises. To find out, I went to the Internet and asked, Is the United States living up to its treaty obligations to provide adequate health, education, and other basic social and economic services to Indian people in exchange for the land all Americans now live on? Out of 77 respondents—Native people replying from throughout Indian Country—not one person said yes.

Nation to Nation is on view at the museum in Washington through 2021. The Treaty of Fort Wayne of 1809 will be on exhibit until January 2018. Following in rotation will be the 1868 Navajo Treaty (scheduled to be on view from February to May 2018), then the first of the 370 treaties made between the United States and Indian tribes, the 1778 Treaty with the Delaware (June to November 2018).