NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

Finalists Present Their Design Concepts for the National Native American Veterans Memorial

The competition to design the National Native American Veterans Memorial received more than 120 submissions, from artists across the world. Five concepts were unanimously chosen as finalists by a jury of Native and non-Native artists, designers, and scholars. Today, the designers shared their concept drawings for the memorial and the ideas and experiences that shaped them.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Designers_2018-02-07.png)

This afternoon in Washington, D.C., the National Museum of the American Indian introduced the artists whose concepts will go forward to the second stage of the competition to design the National Native American Veterans Memorial. Before describing their proposals, the finalists said a few words about the ideas and experiences that led each of them to take part in the project.

James Dinh cited his family’s experience of displacement from their home in Vietnam after the war. His design reflects Dinh's belief that a memorial should be a space, rather than an object, and that remembering is a communal act, as well as a personal one.

Both Daniel SaSuWeh Jones (Ponca Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma) and Enoch Kelly Haney (Seminole Nation of Oklahoma), who worked together on a design, have deep roots in their people's culture. A former principal chief, Haney grew up at a time when the large majority of his nation still spoke Mvskoke. Jones, a former tribal chairman, is taking part in a project to preserve traditional stories in Ponca by re-establishing the songs associated with them and creating bronze statues of their characters.

As a boy, Harvey Pratt (Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes) saw the respect his people gave to those who fought for their nation. A U.S. Marine from 1962 to 1965, he was one of the first Native American soldiers to serve in Vietnam. Decades later the Southern Cheyenne Chiefs Lodge made him a Cheyenne Peace Chief.

Stefanie Rocknak, a sculptor, professor of philosophy, and student of American history, believes that a national memorial to the service and sacrifice of Native American veterans and their families is long overdue. She hopes the memorial will give visitors a sense of awe and reverence.

Leroy Transfield (Māori: Ngai Tahu/Ngati Toa) envisions the memorial as both a single sculptural form and a place that will present stories of bravery, sacrifice, and other inclusive themes in ways that will resonate meaningfully with different visitors in different ways.

The illustrations and descriptions below are excerpted from the artists' proposals.

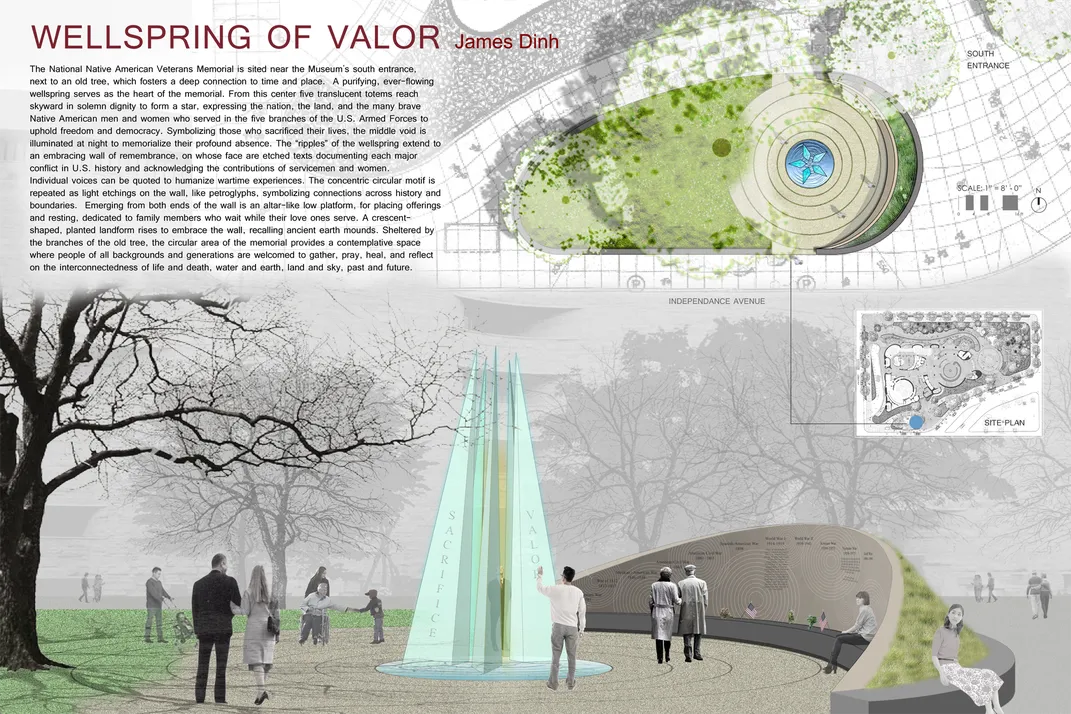

Wellspring of Valor by James Dinh

"The memorial would be sited near the museum’s south entrance, next to an old tree, which fosters a deep connection to time and place. A purifying, ever-flowing wellspring serves as the heart of the memorial. From this center five translucent totems reach skyward in solemn dignity to form a star, expressing the nation, the land, and the many brave Native American men and women who served in the U.S. Armed Forces. Symbolizing those who sacrificed their lives, the middle void is illuminated at night to memorialize their profound absence.

"The 'ripple' of the wellspring extend to an embracing wall of remembrance, on whose face are etched texts documenting each major conflict in U.S. history and acknowledging the contributions of servicemen and women. The concentric circular motif is repeated as light etchings on the wall, like petroglyphs, symbolizing connections across history and boundaries. Emerging from both ends of the wall is a low platform for resting and placing offerings."

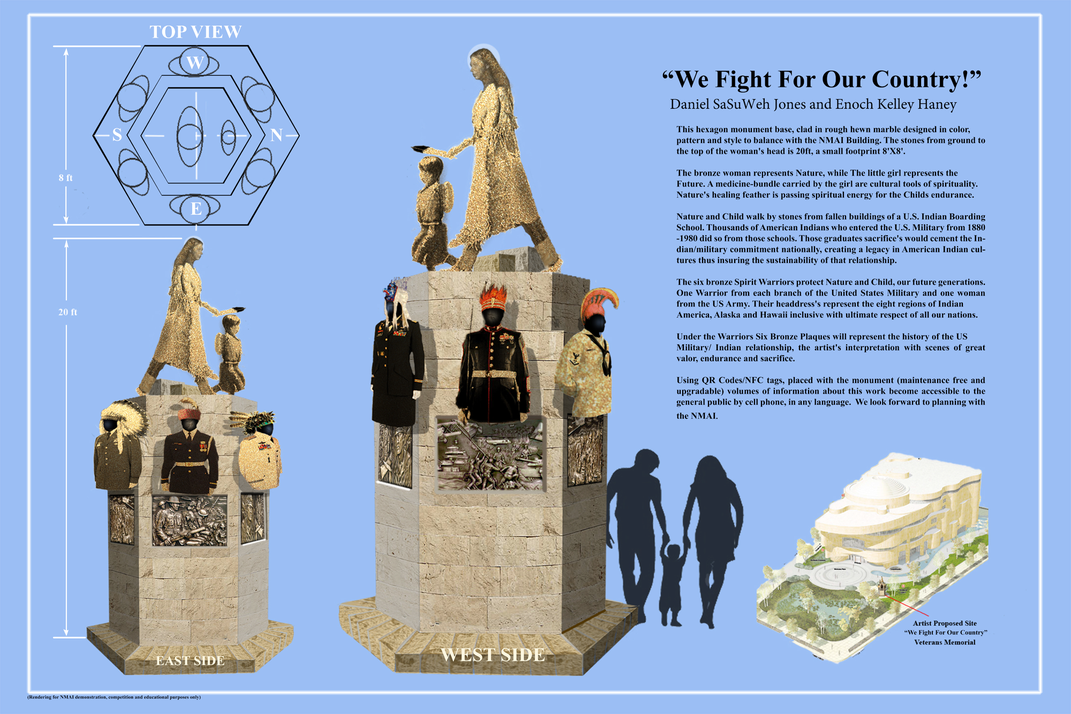

We Fight for Our Country by Daniel SaSuWeh Jones and Enoch Kelly Haney

"The memorial features a bronze sculpture of a woman and child representing Nature and the Future. The girl carries a medicine bundle symbolizing cultural tools of spirituality. Nature’s healing feather is passing spiritual energy for the child’s endurance. Below, six bronze Spirit Warriors surround Nature and Future as a symbol of protection. There is one Warrior from each branch of the military and one representative of women in the forces. The Warriors’ headdresses represent one of the eight regions of Native Americans, inclusive of America, Alaska, and Hawai'i, with ultimate respect for all our nations. Under the Warriors, six bronze plaques show the history of the military/Indian relationship through an artist’s interpretation of great valor, endurance, and sacrifice.

"A compact memorial, the monument would be located north of the Welcome Plaza and stand approximately 20 feet tall with a footprint of about 8 by 8 feet. The hexagonal base would be clad in rough-hewn marble designed in color, pattern, and style to balance with the museum building."

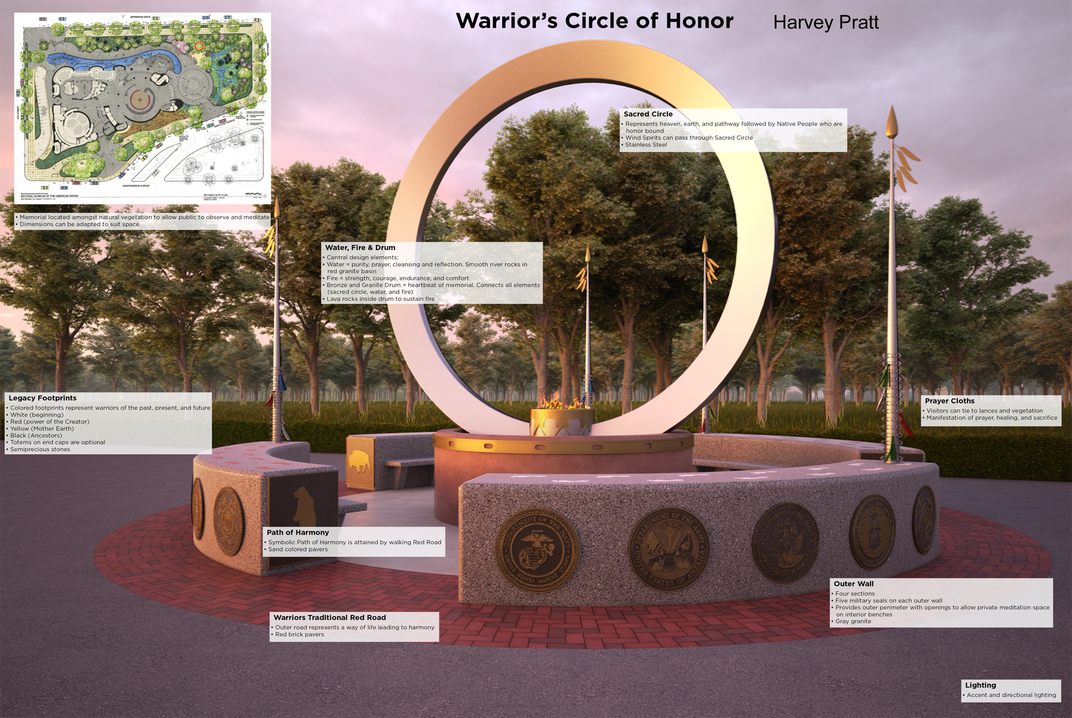

Warrior’s Circle of Honor by Harvey Pratt

"The Sacred Circle represents heaven, earth, and the pathway followed by honor-bound Native People. Wind Spirits can pass through the stainless steel Sacred Circle. Water, fire and the drum are the central design elements within the circle. Water represents purity, prayer, cleansing, and reflection, running over smooth river rocks in a red granite basin. Fire symbolizes strength, courage, endurance, and comfort. The bronze and granite drum is the heartbeat of memorial and connects all the elements.

"The outer wall is comprised of four sections with the five military seals on each section. It provides an outer perimeter and allows private meditation space on interior benches. Legacy Footprints of different colors on top of the outer wall represent warriors of the past, present, and future: white (beginning), red (power of the Creator), yellow (Mother Earth), black (ancestors). The Warriors Traditional Red Road, made of red brick pavers surrounding the outer wall, represents the way of life leading to harmony. The memorial would be located north of the museum's Welcome Plaza."

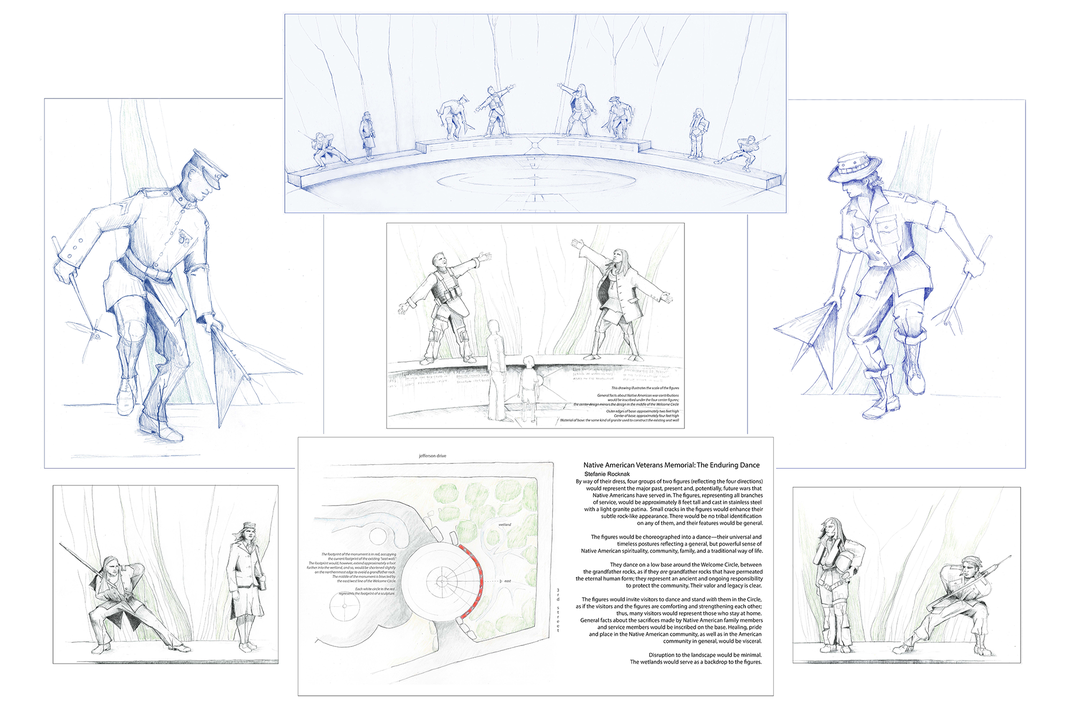

The Enduring Dance by Stefanie Rocknak

"Four groups of two figures are choreographed into a dance—their universal and timeless postures reflecting a general, but powerful, sense of Native American spirituality, community, family, and a traditional way of life. They dance on a low base around the Welcome Circle, between the grandfather rocks, as if they are grandfather rocks that have permeated the eternal human form. They represent valor, legacy, and the ancient and ongoing responsibility to protect the community.

"By way of their dress the figures would represent the major past, present, and, potentially, future wars in which Native Americans have served. The figures, representing all branches of service, would be approximately eight feet tall and cast in stainless steel with a light granite patina. General facts about the sacrifices made by Native American family members and service members would be inscribed on the base. Healing, pride, and place in the Native American community, as well as in the American community in general, would be visceral."

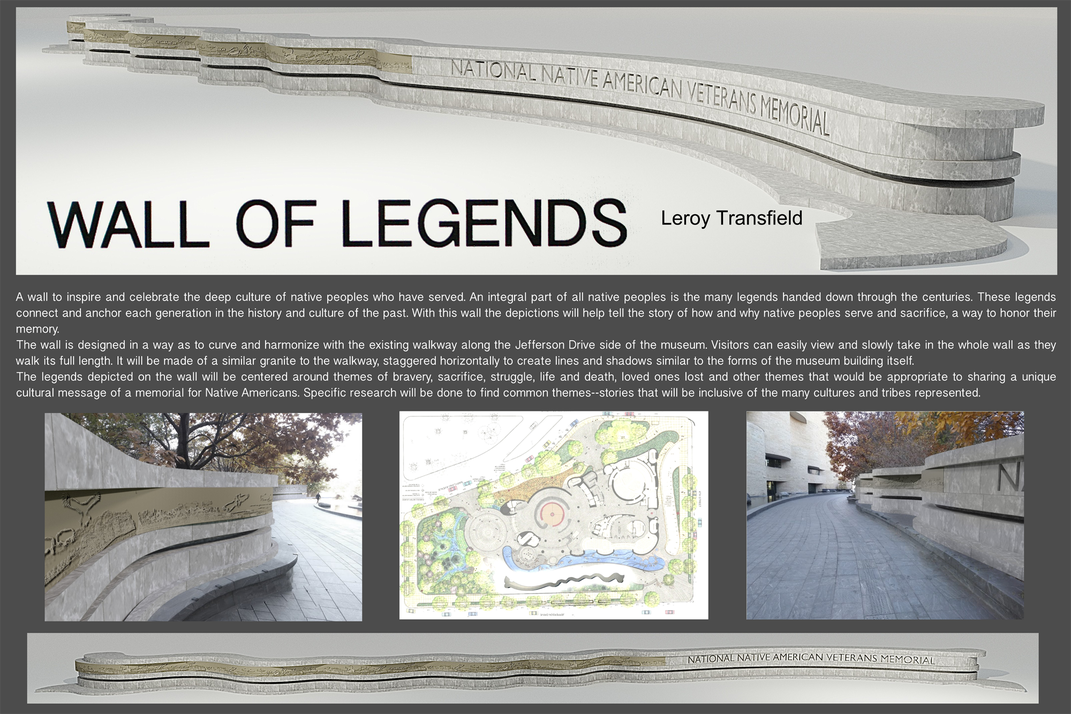

Wall of Legends by Leroy Transfield

"The memorial is a sculptural wall to inspire and celebrate the deep culture of Native peoples who have served. An integral part of all Native peoples is the many legends handed down through the centuries. These legends connect and anchor each generation in the history and culture of the past. Common themes to depict on the wall will be identified—stories will be inclusive of the many cultures and tribes in America and be centered around bravery, sacrifice, struggle, life and death, loved ones lost, and other themes that would be appropriate.

"The wall is designed in a way as to curve and harmonize with the existing walkway along the Jefferson Drive side of the museum. Visitors can easily view and slowly take in the whole wall as they walk its full length. It will be made of granite similar to the walkway, staggered horizontally to create lines and shadows similar to the forms of the museum building itself."

The Competition

Recognizing the importance of giving “all Americans the opportunity to learn of the proud and courageous tradition of service by Native Americans in the Armed Forces of the United States,” Congress commissioned the museum to build a National Native American Veterans Memorial. The museum, together with the National Congress of American Indians and other Native American organizations, formed an advisory committee composed of tribal leaders and Native veterans from across the country who have assisted with outreach to Native American communities and veterans. From 2015 until the summer of 2017, the advisory committee and the museum conducted 35 community consultations to seek input and support for the memorial. These events brought together tribal leaders, Native veterans and community members from throughout the United States and resulted in a shared vision and set of design principles for the memorial.

The first phase of the design competition received 120 completed entries from across the world. The authors of each entry remained anonymous throughout the selection process and were not revealed to the museum’s jury of Native and non-Native artists, designers, and scholars until after the conclusion of the jury session. The jury unanimously selected the five finalists.

These five entries will undergo further development throughout the second stage of the competition to a level that fully explains their spatial, material, and symbolic qualities and how they respond to the vision and design principles for the memorial. The final design concepts will be shown at the museum in Washington and New York from May 19 through June 3. The competition jury will judge the final design concepts and announce a winner July 4. The memorial is slated to open on the grounds of the museum in Washington in 2020.

Holly Stewart is a writer and editor on the staff of the National Museum of the American Indian.