NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

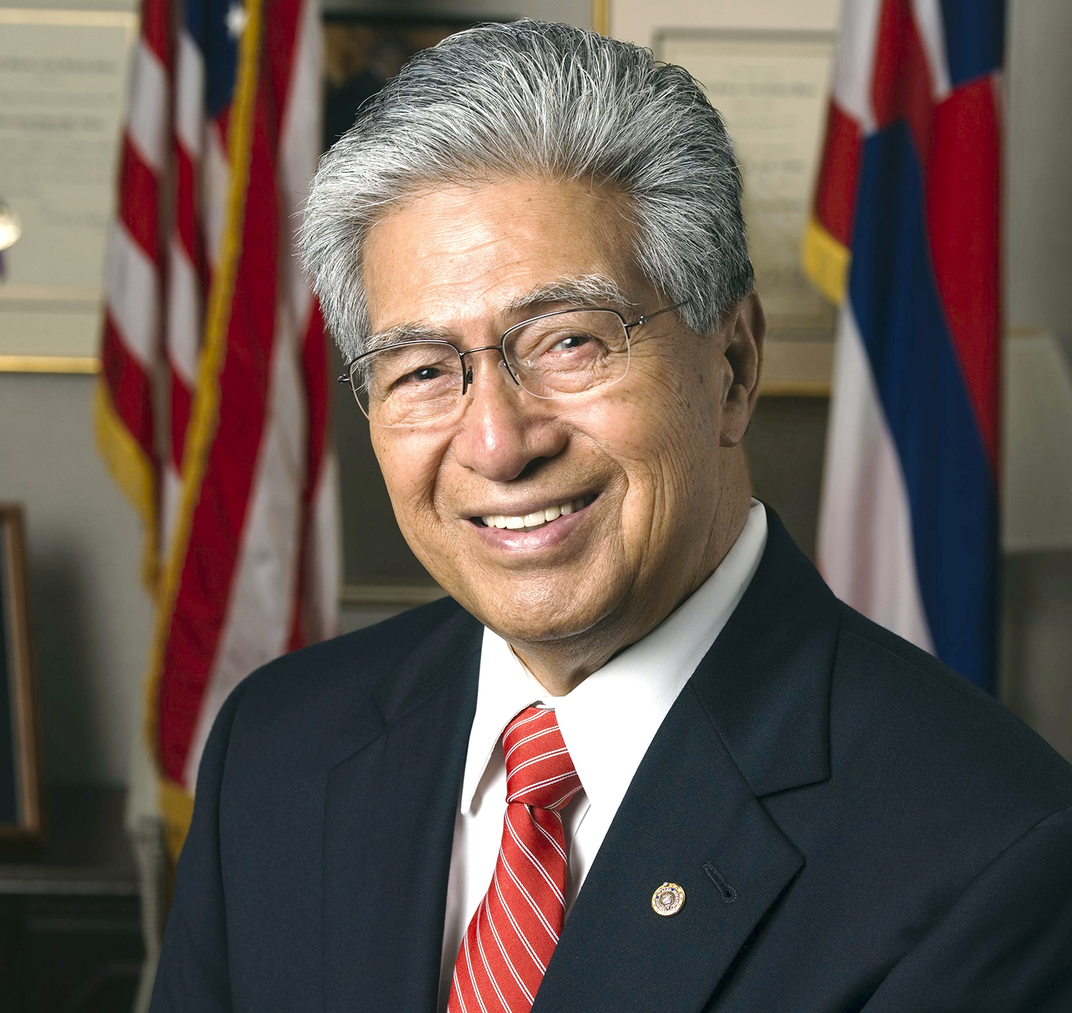

“The Spirit of Aloha Means Nothing Unless We Share It”—Senator Daniel Akaka (1924–2018)

Daniel Kahikina Akaka, who died today at the age of 93, was the first Native Hawaiian to serve in the U.S. Senate. In 2013, shortly after he retired, he spoke with the museum about his determination to protect the languages, cultures, and traditions of the world’s Indigenous peoples; support for Hawaiian self-determination; and hopes for Native Hawaiian young people. We’re republishing Sen. Akaka’s interview tonight in remembrance of his life of service.

:focal(198x95:199x96)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Sen_Akaka_2009.png)

Established in 1989 through an Act of Congress, the National Museum of the American Indian is an institution of living cultures dedicated to advancing knowledge and understanding of the life, languages, literature, history, and arts of the Native peoples of the Western Hemisphere, including the Native people of Hawai‛i. Daniel Kahikina Akaka (1924–2018) is the first Native Hawaiian to serve in the U.S. Senate. In 2013, shortly after he retired, he spoke with the museum. We're republishing Sen. Akaka's interview today in remembrance of his life of service.

Please introduce yourself with your name and title.

My name is Daniel Kahikina Akaka. In January 2013, I retired from the United States Senate after more than 36 years of representing the people of Hawai‘i in Congress. I began my tenure in the House of Representatives in 1977 and was appointed to the Senate in 1990, becoming the first Native Hawaiian to serve in that chamber. In November of that year, I won the special election to the Senate and would be re-elected to the seat three more times. Throughout my career in the Senate, I served on the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs. I served as its chairman in the 112th Congress.

Can you share with us your Hawaiian name and its English translation?

My Hawaiian name is Kahikina; literally translated it means "to the east.” I am named after my father.

What responsibilities do you have as a national leader and tribal elder?

As a national leader, I've committed myself to a lifelong goal of working to protect the language, culture, and traditions of Indigenous peoples. An essential component to this is grooming future leaders to ensure they practice and perpetuate their cultural values, which is why I've dedicated my time in retirement to mentor our future leaders. I hope that in the future all the work I've done in the state of Hawai‘i and in the Congress will help Native Hawaiians achieve self-determination and enable them to establish a governing entity.

Moreover, I hope that our country and world can get to a point where we all implement a good model for Indigenous peoples that protects their right to self-determination and preserves their unique cultures and traditions.

How did your experience prepare you to lead your community?

My family and upbringing instilled in me a strong foundation and life purpose—to help and serve the people of Hawai‘i. I grew up immersed in Native Hawaiian cultural practices and traditions and took pride in my heritage.

From my exposure to various cultures in the Pacific when I served in the Army during World War II to seeing first-hand the displacement of Indigenous peoples throughout the world as I visited various places as a member of Congress, I came to realize that I needed not only to serve as a leader for the Native Hawaiian community, but moreover to help all Indigenous peoples preserve their language, culture, and traditions.

As a member of Congress, I witnessed and learned more about the startling disparities faced by Native Hawaiians and was motivated to identify a way to unite Native Hawaiians and give them the capacity to govern themselves and take care of our people. This continues to be a sincere passion for me, and I firmly believe that when Native Hawaiians are successful in establishing a governing entity, they will serve as a model for Indigenous groups around the world.

Who inspired you as a mentor?

There are a number of individuals who helped groom and mentor me from my youth through my professional career. My brother, Reverend Abraham Akaka, was one of my first mentors and advocates. I admire and cherish him dearly. I still vividly remember the inspiring conversations I had with him over breakfast. Our discussions were often about faith and spirituality, but I will never forget his encouragement to embrace and understand diversity. He believed that out of diversity arises strength and power. He also advocated for raising the level of Native Hawaiians and encouraged me to do whatever I could to bring our people together.

My wife, Millie, is also my lifelong supporter who made it possible for me to accomplish all that I have in my life.

Two important individuals who specifically helped me get to the U.S. Congress were Hawai‘i Governors John Burns and George Ariyoshi. They both saw in me qualities that they believed were needed in our state and in the Native Hawaiian community. They provided me the opportunities to serve various communities throughout the state and pushed me to strive for higher office.

I am extremely grateful to these four individuals for their belief in me and their tireless support.

Are you a descendant of a historical leader?

No, I am not aware of any of my ancestors who were historical leaders.

Where is the Native Hawaiian community located? Where was the community originally from?

Our homeland consists of the islands of Hawai‘i, located in the Pacific Ocean. It is made up of eight major islands and 124 minor islands encompassing 4,112,955 acres. Hawai‘i was originally settled by voyagers from central and eastern Polynesia who travelled great distances in double-hulled voyaging canoes to arrive in Hawai‘i, perhaps as early as 300 AD.

What is a significant point in history from your community that you'd like to share?

On January 16, 1893, at the order of United States Minister to Hawaii John Stevens, a contingent of Marines from the USS Boston marched through Honolulu to a building located near both the government building and the palace. The next day local non-Hawaiian revolutionaries seized the government building and demanded that Queen Lili‘uokalani abdicate the monarchy. Minister Stevens immediately recognized the rebels’ provisional government and placed it under the United States’ protection. Since the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i, Native Hawaiians have been displaced from our land and our right to self-governance and self-determination.

It took 100 years for the United States to formally acknowledge their role in this event. In 1993 President Bill Clinton signed into law P.L. 103-150. This resolution, which I sponsored, acknowledges the role the United States and its agents played in the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i and sets forward a path towards reconciliation between the United States government and the Native Hawaiian people.

Approximately how many members are in the Hawaiian Native community? What are the criteria to become a member?

According to the 2010 census, there are more than 500,000 individuals who identify as full or part Native Hawaiian in the United States. Of that number, more than 280,000 live in Hawai‘i.

Native Hawaiians do not have a governing entity or organic documents that establish the criteria to be a member of such an entity. However, in 2011 the state of Hawai‘i enacted Act 195 to establish a Native Hawaiian Roll Commission. Individuals on the roll will participate in the organization of a Native Hawaiian governing entity. To be on this roll, an individual must be a lineal descendant of the aboriginal people who resided in the Hawaiian Islands prior to 1778, or be eligible for Hawaiian Home Lands or a lineal descendant of a person who is eligible for Hawaiian Home Lands.

Is your language still spoken on your homelands? If so, what percentage of your people would you estimate are fluent speakers?

Yes, our language is spoken on our homelands due to the persistence of dedicated professionals in our community who worked tirelessly to ensure our language was preserved. Our language was nearly lost due to a number of significant historical events. First, after the arrival American missionaries, our oral language transitioned to a written language. Later the language was banned in all schools and displaced by English. I experienced first-hand the impact of this ban and was forbidden to speak my native tongue.

In 1984 a movement began to perpetuate our language, and the first Hawaiian language immersion preschool was opened. Hawai‘i is now the only state with a designated native language, Hawaiian, as one of its two official state languages. Moreover, it is now possible to receive an education in Hawaiian immersion from preschool through a doctoral degree. Hawaiian language content is now available through multiple media sources, such as the Internet, television programs, and websites.

According to the 2006–2008 American Community Survey, nearly 25 percent of Hawai‘i’s population speaks a language other than English at home. Of this group, more than 6 percent are Native Hawaiian speakers.

What economic enterprises does your Native community own?

Our community does not own any economic enterprises. However, Native Hawaiians are successful business owners and many participate in the U.S. Small Business Administration’s 8(a) Business Development Program as a means to support the community.

What annual events does the Native Hawaiian community sponsor?

Many different organizations in our community hold different annual events. These can range from annual conferences with government and community officials, to family days, workshops with cultural practitioners, language seminars, and hula festivals.

One of the more prominent and longer-running events is a hula festival called the Merrie Monarch Festival. It's a week-long event hosted every spring in Hilo on the island of Hawai‘i. Many hālau hula, or hula schools—not just from across the state, but from across the nation and even internationally—participate in hula exhibitions and competitions. Merrie Monarch has received worldwide attention and is noted for its cultural significance and community impact.

What other attractions are available for visitors on your land?

Hawai‘i is known worldwide for its natural beauty. Many people are familiar with our sandy beaches and our lush mountains, such as one popularly known as Diamond Head on O‘ahu. However, we also have National Parks that have great cultural significance, such as Haleakalā National Park on Maui, or Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park and Pu‘uhonua O Hōnaunau National Historical Park on the island of Hawai‘i.

Hawai‘i is also home to sites of national historical significance, such as the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument where the USS Arizona Memorial is located, as well as the Battleship Missouri Memorial and the USS Bowfin Submarine Museum and Park. In addition ‘Iolani Palace on O‘ahu is the only site in the United States that was used as an official residence by a reigning monarch. It's a National Historic Landmark listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Another noteworthy place in Hawai‘i is the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. While it isn’t an attraction available for visitors, Papahānaumokuākea is the single largest conservation area in the United States and one of the largest ocean sanctuaries in the world. This place speaks to the splendor and uniqueness of my home.

How is your traditional Native community government set up?

Prior to Western contact, our island nation had an organized and stable land tenure system under the stewardship of chiefly rulers. Native Hawaiians evolved a system of self-governance and a highly organized, self-sufficient, subsistent social system based on communal land tenure, with a sophisticated language, culture, and religion. This society was marked by reciprocal obligation and support between the chiefs and the people.

In 1810 the Native Hawaiian political, economic, and social structure was unified under a monarchy led by King Kamehameha I. The authority of the king was derived from the gods, and he was a trustee of the land and other natural resources of the islands, which were held communally.

Is there a functional, traditional entity of leadership in addition to your modern government system? If so, how are leaders chosen?

Native Hawaiians have not reorganized a governing entity since the kingdom was overthrown in 1893. Although we have many prominent leaders throughout our communities who are successful because of their strong characters and respect of our culture and traditions, Native Hawaiians do not have a governing entity that is chosen and led by our people.

What message would you like to share with the youth of your Native community?

Foremost, I encourage the youth of my Native community to take pride in the place we call home—Hawai‘i. Learn, internalize, and appreciate our Native language, culture, traditions, people, and natural environment. We will lose our identity as Hawai‘i if we lose this. Commit yourselves to preserving the identity of Hawai‘i and the identity of Indigenous peoples around the world.

As I see it, Hawai‘i is the piko—a navel or center—of the universe. We have so much to offer and we need to do all we can to share what we have with the world. Ultimately I encourage the youth to give back to people and the world by using all that makes up our special identity as Native Hawaiians.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

This is something I have said before, but it remains very important to me and the Hawaiian people: If at any time in your life you are given aloha, appreciate it, live it and pass it on, because that's the nature of aloha and that is the spirit of aloha. It means nothing unless you share it.

Mahalo, thank you, for giving me the opportunity to share a little about my community and our people with you.

Thank you.