NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

A Brief Balance of Power—The 1778 Treaty with the Delaware Nation

The Treaty with the Delaware Nation, signed at Fort Pitt in September 1778, represents a time when the newly independent United States needed American Indian allies to drive British troops from forts and outposts west of the Appalachian Mountains. Despite the treaty’s provisions, however, conflict continued in the Ohio Territory, leading the Delaware people to look for safer lands farther north and west. This month, delegations from the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown, in southern Ontario; the Delaware Tribe of Indians, in northeastern, Oklahoma; and the Delaware Nation, in central Oklahoma, came to the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., to see the Treaty of Fort Pitt placed on exhibit and to honor their forebears, who made their marks to secure the future of their people.

:focal(716x172:717x173)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Fort_Pitt_Unveiling_1500_x_785.png)

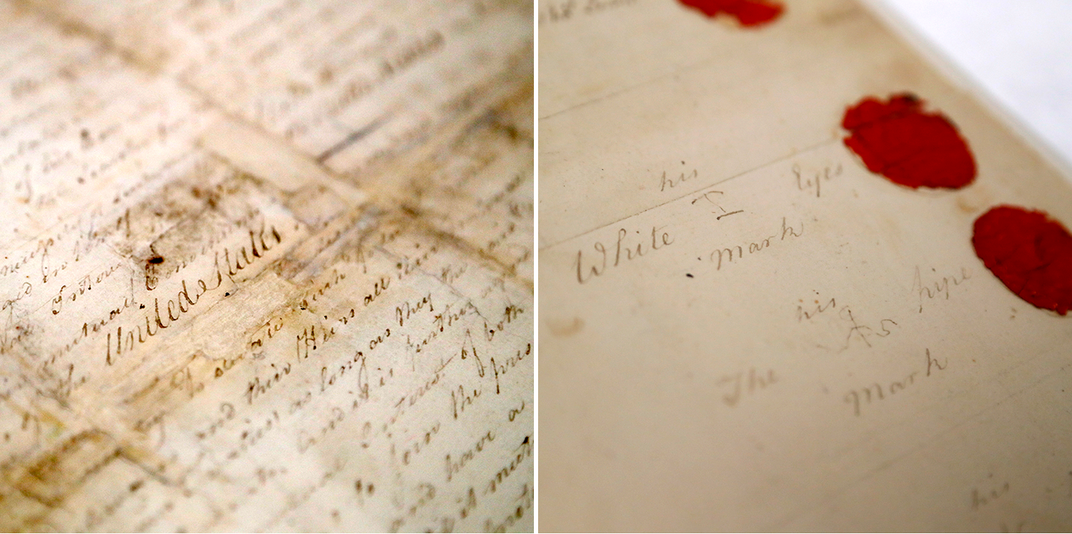

On September 17, 1778, the newly formed United States Continental Congress dispatched a treaty commission to the confluence of the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers to negotiate America’s first treaty of peace with an American Indian tribe. Three leaders—named in the treaty as "Capt. White Eyes, Capt. John Kill Buck, Junior, and Capt. Pipe, Deputies and Chief Men of the Delaware Nation"—represented the Lenape (Delaware) people. During colonial times, Lenape communities had been compelled to move west from their historic home along the Delaware and lower Hudson River watersheds to lands between modern-day Pittsburgh and Detroit. General Andrew Lewis and his brother Thomas served as commissioners on behalf of the United States. Eleven other Americans witnessed what would become known as the Treaty of Fort Pitt.

On Thursday, May 10, 2018, three current Delaware tribal leaders brought delegations to Washington, D.C., to witness the unveiling of the treaty their ancestors made as it was installed in the exhibition Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations at the National Museum of the American Indian. The three tribal leaders are President Deborah Dotson, Delaware Nation (Anadarko, Oklahoma); Chief Chester “Chet’ Brooks, Delaware Tribe of Indians (Bartlesville, Oklahoma); and Chief Denise Stonefish, Delaware Nation at Moraviantown (Thamesville, Ontario, Canada).

Kevin Gover, director of the National Museum of American Indian, opened the unveiling ceremony by welcoming the visiting tribal delegations. He then introduced the Honorable David. S. Ferriero, archivist of the United States. Mr. Ferriero spoke about the fact that treaties are still relevant today. He also announced an important new initiative at the National Archives to digitize 377 ratified Indian treaties and make them available online in a public catalogue. The leaders of the three Delaware Nations then addressed the audience. All agreed that it was a proud day for their people and an honor to recognize the leaders who put their marks on the Treaty of Fort Pitt.

The negotiations at Fort Pitt, convened by the United States, took place during the early years of the Revolutionary War after many Native nations had allied themselves with the British. The Americans sought from the Delaware security, assistance, and trade. The Delaware, who had clashed with other Native groups as they sought to re-establish their nation beyond European–American settlement, wanted to protect their new lands in the Ohio Territory and strengthen their position in the region.

The two nation's goals stand out clearly in the treaty. The first article calls on both parties to forgive any grievances between them. The second refers to their “perpetual peace and friendship” going forward and states that the two nations shall assist each other if either is “engaged in a just and necessary war with any other nation or nations.”

The treaty’s third and longest article refers to the United States’ war against the king of England. It specifies that the Delaware people will allow American troops safe passage across Delaware lands to attack Britain’s western posts and forts; provide the Americans with food and supplies, including horses, for reasonable compensation; and assist the American forces “with such a number of their best and most expert warriors as they can spare, consistent with their own safety.”

The fourth article calls for the resolution of future disputes between the two nations and their citizens through negotiations and courts that will respect the “laws, customs, and usages” of both peoples, as well as “natural law.” It also requires the arrest and extradition of “criminal fugitives, servants, or slaves.” The fifth article recognizes that the alliance makes it impossible for the Delaware people to continue to trade with the British and their allies and calls for the establishment “as far as the United States may have it in their power” of fair and well-regulated trade between the United States and the Delaware Nation.

In the last article of the treaty, the United States recognizes Delaware sovereignty. The new nation promises “to guarantee to the aforesaid nation of Delawares, and their heirs, all their territorial rights in the fullest and most ample manner, as it hath been bounded by former treaties, as long as they the said Delaware nation shall abide by, and hold fast the chain of friendship now entered into.” The article also suggests, “should it be conducive for the mutual interest of both parties,” that the Delaware “invite any other tribes who have been friends to the interest of the United States” to join a Delaware-led confederation that would become, with the approval of Congress, a new state with representation in the U.S. Congress.

Robert N. Clinton, Foundation Professor at the Sandra Day O’Connor School of Law and a faculty member of the Arizona State University American Indian Studies Program, says that we can see a balance of power in this treaty, negotiated by the United States during the Revolutionary War, when its survival was in question.

That balance did not last. White Eyes died not long after the treaty was signed, while he was serving as a lieutenant colonel in the Continental Army. Historians disagree over how he died; at the unveiling, Chief Brooks referred to his murder and the Americans' attempt to conceal it. The United States could not protect the Ohio Territory from the British or from American settlers who continued to push west. Many Delaware groups joined forces with the British.

In 1779 a Delaware delegation visited Philadelphia to raise their grievances with the Continental Congress, without success. In March 1782 Pennsylvania militiamen killed approximately 96 Delaware people at Gnadenhutten, in what is now eastern Ohio. Forced by the British from their homes there the year before, the Delaware group had returned to harvest what they could salvage from their fields. The families of the victims eventually established the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown, Ontario. By 1782 violence compelled the group known as the Absentee Delaware, now the Delaware Nation, to move into Spanish territory west of the Mississippi River. Pressured by European–American settlement backed up by new treaties and laws, most of the Delaware people continued to move west, to Indiana, then Missouri, then Kansas, and finally Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. Some moved to upstate New York, then to Wisconsin.

No American Indian state was ever created.

The Treaty of Fort Pitt is the ninth treaty to be lent to the museum by the National Archives for display in Nation to Nation. It will be on view until fall 2018. The next treaty to go on display will be the Treaty with the Sioux and Arapaho negotiated at Fort Laramie in 1868. For more information on U.S.–American Indian treaties and other American Indian records at the National Archives, see the Archives' website on Native American Heritage.