NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

Spotlight on Collections: Reuniting Objects and Expedition Field Notes

The collections of the National Museum of the American Indian include thousands of objects and images acquired during expeditions conducted or sponsored by our predecessor institution, the Museum of the American Indian–Heye Foundation. While some expeditions are well documented in collectors’ field notes and early publications, much of the information about specific objects or the individuals associated with them was never recorded on the museum’s catalog cards. A long-term, multi-institutional project to reconstruct objects’ acquisitions histories is reuniting this information with the collections. Here are a few things we’ve learned so far.

:focal(1247x855:1248x856)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Soboba_olla_071952_EH_Davis_sketch_copy.jpg)

The collections of the National Museum of the American Indian include thousands of objects and images acquired during expeditions conducted or sponsored by our predecessor institution, the Museum of the American Indian–Heye Foundation (MAI). The MAI often sent staff anthropologists and collectors to Native and Indigenous communities in the Americas to collect material and gather information. While some expeditions were well documented through publications or in collectors’ field notes, much of the information about specific objects or the individuals associated with them was never recorded on the museum’s catalog cards. As part of our ongoing Retro-Accession Lot Project, we are working on reuniting this information with the collections. Below are a few of the discoveries we’ve made so far.

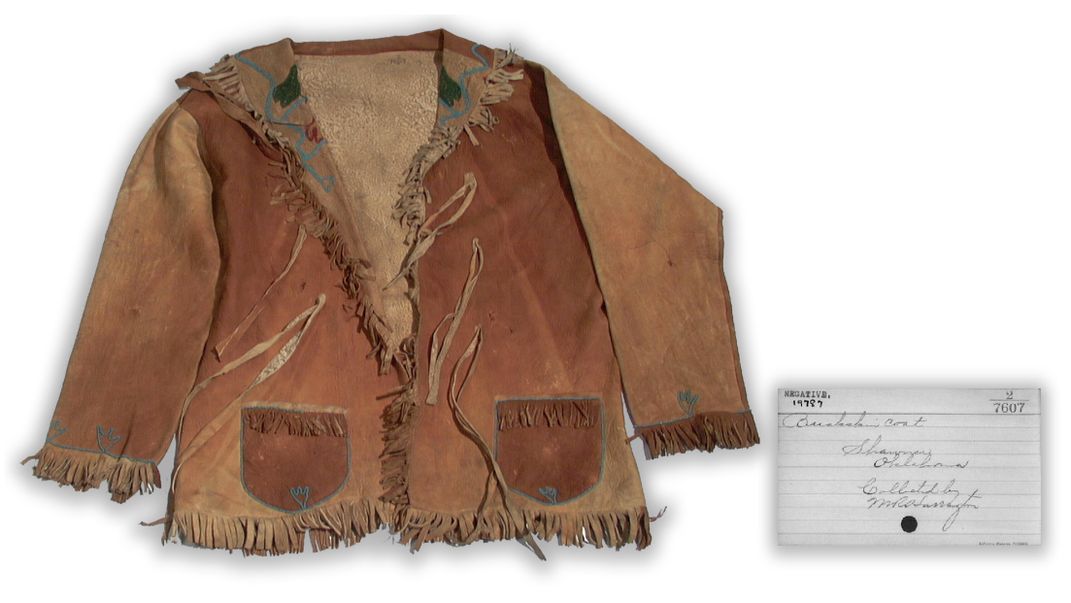

Anthropologist and archaeologist Mark Raymond Harrington (1882–1971) worked for George Heye and the MAI, which Heye founded, from 1908 to 1928. During that time, Harrington traveled extensively to Native communities throughout the United States collecting objects of material culture and shipping them to New York City to be catalogued. In 1910, he visited communities in Oklahoma and collected hundreds of objects, including this Shawnee coat.

As you can see from the catalog card, the only information originally recorded for this coat was a brief description, the culture, and that it had been collected by Harrington in Oklahoma. Harrington, however, was a dedicated fieldworker and kept detailed field notes about objects he collected, including the names of the individuals from whom he purchased them, the prices he paid, and the names of objects in Native languages. He also often took photographs documenting how things were worn or used. His notebooks and photographs—maintained in the Archives of the National Museum of the American Indian as Museum of the American Indian/Heye Foundation Records—indicate that this coat belonged to Chief Joe Billy, the traditional leader of the Big Jim Band of Absentee Shawnee. One hundred years later, the coat has been reconnected to its Native owner.

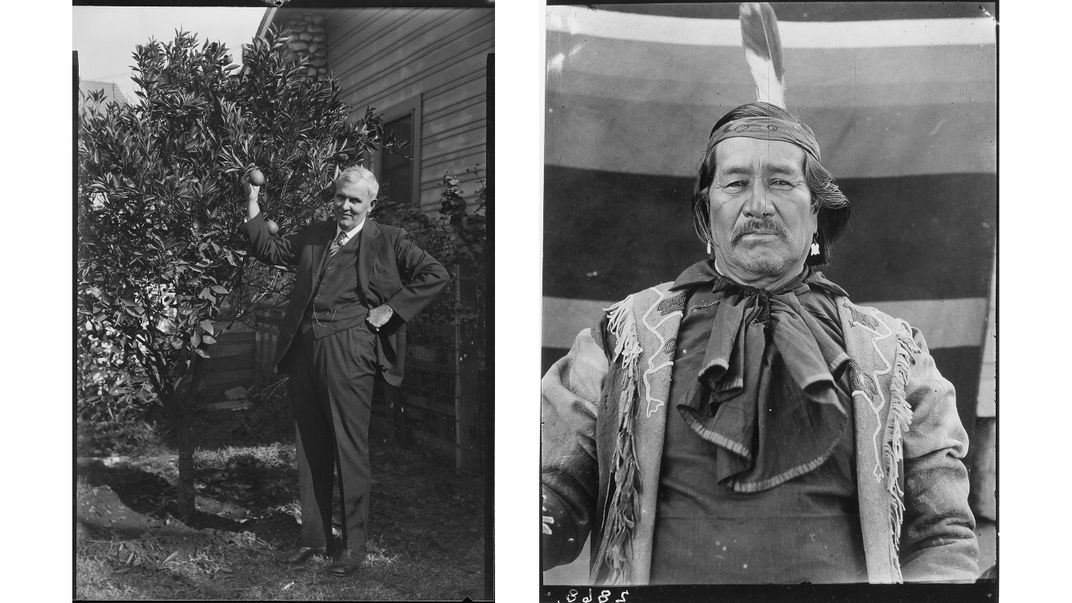

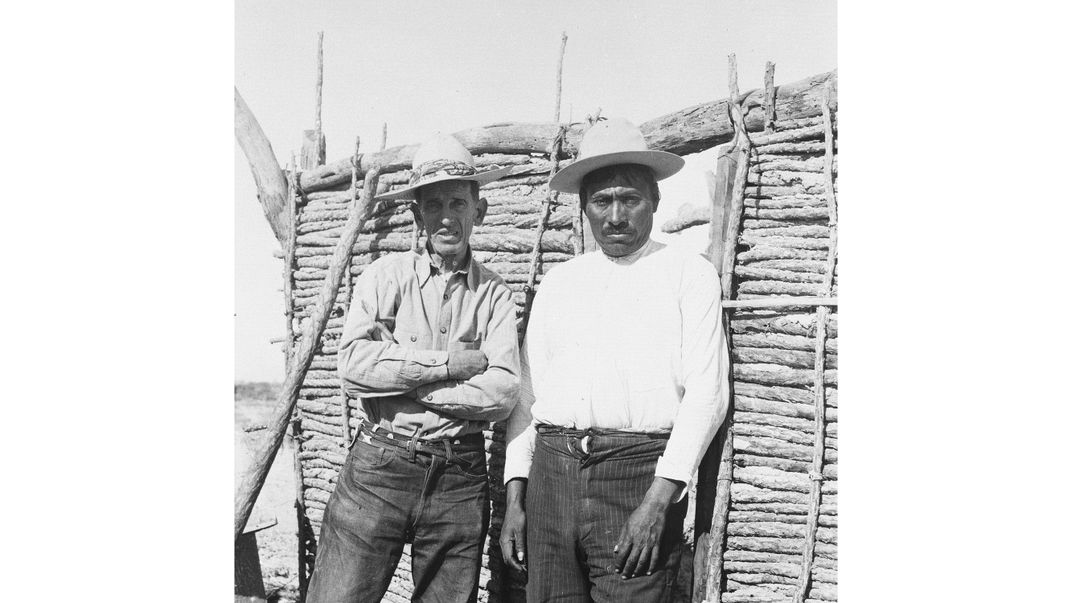

Edward H. Davis (1862–1951) was a field collector for the MAI, working primarily in Southern California and Northern Mexico. Davis, originally from New York, settled on a ranch in Mesa Grande, California, northeast of San Diego, and soon became friendly with members of local Native communities. He began collecting objects and building relationships with his Indigenous neighbors and used photography to document their lives and cultures. He recorded information about the objects he collected in his journals, and his artistic skills are evident in his sketchbooks, which illustrate objects and landscapes he encountered on his trips.

Davis’s journals and sketchbooks are part of the Huntington Free Library Native American Collection—formerly held by the MAI, now the centerpiece of the Cornell University Library’s Rare and Manuscript Collections. As part of our project, the museum has received copies of this material from Cornell. Our Archives maintain additional material from Davis, including field lists and correspondence, as well as the Edward H. Davis photograph collection. Taken as a whole, these sources help create a clearer picture of how objects Davis collected were used in traditional Native life.

In 1917, during a collecting trip in Southern California, Davis purchased an olla—shown at the top of this article with a drawing of the olla made in one of his sketchbooks—from Soledad Lala, a Soboba Luiseño woman. Davis also took a photograph of Mrs. Lala with the olla and another he purchased. On the back of the photograph, he wrote, “Soledad Lala [Laila]. Sobaba [sic] Nov. 13 1917. California. Bought these olas [sic] & 2 gambling games.”

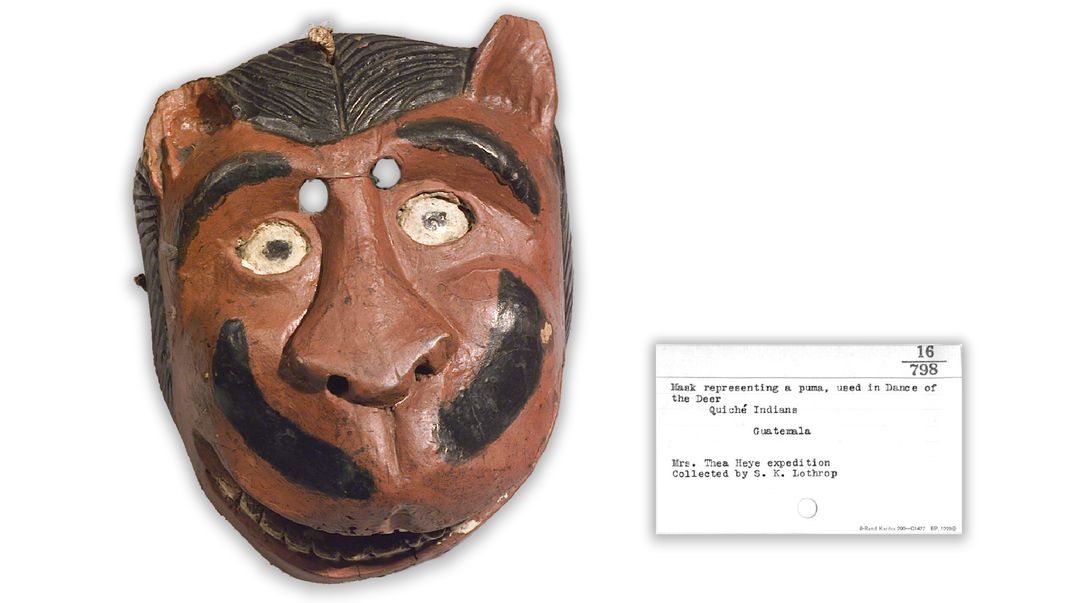

Anthropologist and archaeologist Samuel K. Lothrop (1892–1965) worked primarily in Latin America. Like other professional anthropologists, Lothrop was associated with several institutions throughout his career, and his papers are dispersed in multiple archives. He was a member of the staff of the MAI from 1923 to 1931, after which he accepted a position at his alma mater, Harvard, on the staff of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. We sought out his records in the Peabody Museum Archives to discover more about his work for the MAI. Lothrop kept beautifully illustrated journals of his expeditions, documenting his daily experiences and the people he encountered, and including colorful hand-drawn maps of the areas where he worked.

In 1925 and 1926, Lothrop conducted MAI’s Central American Expedition. During this trip, he traveled in Guatemala, collecting for the museum. Among the things he acquired there is a group of K'iche' Maya (Quiché) masks and costumes used in different dances. An excerpt from Lothrop’s notes in the Peabody Museum Archives (Samuel K. Lothrop and Joy Mahler papers collection #996-27) describes his visit with Miguel Chuc, a well-known K'iche' Maya mask-maker:

Then we went to the house of Miguel Chuc, the maker of masks. . . . His father, grandfather, have all been makers of masks. He invited us to his private salita where I explained my mission. There upon he led us through series of no less than 10 dusky rooms lined with shelves and piled ceiling high with costumes—and offered to sell me anything I could pay for, pointing out that some were expensive.

After returning to New York, Lothrop documented the masks and costumes, and the dances in which they were worn, in a paper for MAI’s Indian Notes. In 1928, Lothrop returned to Guatemala on an expedition funded by Thea Heye, George Heye’s wife, and again visited Miguel Chuc. On Monday, March 12, 1928, Lothrop wrote in his journal:

Off early for Totonicapan. . . .Thence I went to the mask maker’s, Miguel Chuc. He is a dear. I presented my pamphlet & he was pleased to see his things in print. We then pulled over his stock & I picked out some good duplicate material for exchange.…

As the museum’s Retro-Accession Lot Project moves forward and we work to create more accurate provenance records, we’ll continue to reconnect the objects in our collections with the individuals who made and used them, as well as the collectors who acquired them. In the process, we hope to learn more about these people and their lives.

You can read more about the Retro-Accession Lot Project here. Discover more objects and photographs in the museum’s collections at the Smithsonian online Collections Search Center.

Nathan Sowry, the museum's reference archivist, just published an article on the career and correspondence of Mark R. Harrington on the Smithsonian Collections Blog.

Maria Galban is collections documentation manager at the National Museum of the American Indian. She began her career with the museum in 2003 working on the move of the collections from New York to Maryland, and later served as research assistant for the exhibition Infinity of Nations: Art and History in the Collections of the National Museum of the American Indian. Since 2012 she has worked as the primary researcher on the Retro-Accession Lot Project.