NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

How Native Americans Bring Depth of Understanding to the Nation’s National Parks

On National Park Service Founders Day, the museum looks at the changing relationship between Native Americans and the National Park Service through the eyes of three Native rangers and interpreters: “I think Native interpreters steeped in their own tribal cultures are inclined to go the extra mile to educate the public about other vantage points of an historical event or issue,” writes Roger Amerman (Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma). “I worked extremely hard to tell a complicated story. Even when I was off the clock, I was still thinking of how to add to the story of my park.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Indigenous_wedding_on_Assateague_Island.jpg)

The artist George Catlin proposed the idea of national parks in 1841, in his book Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians. Ten years before, Catlin had set out for St. Louis to see the United States’ new western lands. In 1832, he began a journey that took him 1,800 miles up the Missouri River. All along the way, he met and sketched Native tribes and individuals where they lived. Through these travels and interactions, Catlin grew concerned that the expansion of the United States would threaten the Indigenous nations and the beautiful wilderness and wildlife of the land. In the Dakotas, Catlin wrote that this world should be preserved “by some great protecting policy of government . . . in a magnificent park, . . . a nation’s park, containing man and beast, in all the wild and freshness of their nature’s beauty!”

In 1864, the federal government began to act on Catlin’s vision when it granted Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of giant sequoias to the state of California to be “held for public use, . . . inalienable for time.” In 1872, the United States pioneered a different modelwhen it established Yellowstone as a national park—perhaps because the Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho territories had not yet been organized into states. The National Park Service was created by the Organic Act of 1916, signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on August 25. On this 104that National Park Service Founders Day, we recognize and celebrate the preservation and conservation efforts of the National Park Service.

The National Park Service protects 400 areas—lands and waters in each of the 50 states, U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia that total 84 million acres. Iconic parks include the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Grand Canyon National Park, Everglades National Park, Yosemite National Park, and the National Mall and Memorial Parks in Washington, D.C. Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve in Alaska is the largest park. The National Park Service also protects more than 121 million museum objects; 68,000 archaeological sites; 27,000 historic structures; 2,461 natural historic landmarks; 40 national heritage areas; and 17,000 miles of trails.

Although the word wilderness has come to mean areas uninhabited, and largely unchanged, by humankind, in fact hundreds of Native sites are located on National Park Service lands. Yellowstone alone was cleared of its Shoshone, Bannock, Crow, Nez Perce, and other Native peoples by the treaties of Fort Bridger and Laramie, signed in 1868, before the park was established; Department of the Interior policies enforced by the U.S. Army during the 1870s and ’80s; the Lacey Act of 1894, which prohibited hunting within park boundaries, including traditional tribal hunting rights; and Supreme Court decision in Ward v. Race Horse (1896), which determined that the creation of the national park and the Lacey Act took precedence over treaty rights.

The Supreme Court overruled the Race Horse decision in 1999, after a challenge by the Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians, although tribal rights continue to be argued in state courts. And today the National Park Service works with Native partners to preserve archaeological, historic, and natural sites. Collaborations include the Tribal Preservation Program, American Indian Liaison Office, and Ethnography Program. In many parks, Native American experts interpret Native sites for the Park Service and its many visitors. For Founders Day, the museum has asked three individuals affiliated with National Park Service Native sites to share their experiences—two old hands who helped create greater roles for Native staff members and communities, and one young interpreter whose career will bring changes we can only imagine.

“One of the biggest challenges was getting the Park Service to say that almost all its sites have a tribal story.”

My name is W. Otis Halfmoon. I was born in 1952 in Lewiston, Idaho—twelve miles away from my hometown of Lapwai, Idaho, on the Nez Perce Indian Reservation. My father is Richard A. Halfmoon. My mother is Nancy Jackson Halfmoon. On both sides of my family, I have ancestors who fought and died in the Nez Perce Campaign of 1877.

In the ways of the Nez Perce people, I have had three names bestowed to me. When I was a young boy, my name was Koosetimna (Water Heart). Then when I was a teenager, I was given the name of Peopeo Talmalwiot (Leader Pelican). When I became an adult, my mom gave me my present name of Pahkatos Owyeen (Five Wounds). The last name was “official” because my family had a huge giveaway.

I was raised on Nez Perce homeland, reservation land, and ceded land. My father took me to the mountains and taught me the ways of fishing, hunting, and gathering foods. He also taught me the spirituality of the mountains, waters, and elements of nature. Even as a young boy, I went with my dad to the sweat lodges to listen to the older men, and as I got older, to participate in the sweat. As a teenager I participated in the war dances and ceremonial dances of the Nez Perce. I learned the songs from the older Nez Perce singers. It has to be stated that my father was one of our leaders with the governing body called the Nez Perce Tribal Executive. He also instilled in me the importance of getting an education. I received my BA from Washington State University.

Back in 1965, my father and his friends were tearing down this old structure. Soon, an Anglo guy showed up and told my dad and the rest of the crew to stop tearing down the building because the National Park Service was going to create a new site. At that time, my father was the chairman of the tribe, and he had never heard this news. Once he was back in his office, he delegated a couple of the members to research the project, and they found it was true. The tribe contacted Senator Frank Church to inquire into it. To make a long story short, the Tribal Council decided to endorse the project, and that was the beginning of the Nez Perce National Historical Park. The main intent behind the site was to interpret Nez Perce history and culture, Lewis and Clark, and the missionaries that came into Nez Perce homeland.

As a teenager, I used to go to “the park” to listen to the Anglo interpreters talk about my people. I got a kick out of it, because sometimes those stories were really changed. I knew my tribal history, and the interpreters didn’t like having this teenager correct them. That was my first exposure to the National Park Service, and it did get me thinking that I could do this work.

In the mid-1970s, I applied to be an interpreter for Nez Perce National Historic Park. The requirements were some college credits and knowledge of Nez Perce culture. They hired an Anglo person over me. When I followed up with the superintendent, he told me I wasn’t selected is because of my college transcript: My grades were good, but I didn’t have any Native American history or literature. I was shocked. When I went to college, I wanted to learn more about the White People. I already knew how to be an Indian! Anyway, in 1990 I was hired into the National Park Service as an interpreter at the Big Hole National Battlefield near Wisdom, Montana.

My Park Service career was varied. From Big Hole I transferred to the Big Horn Canyon National Recreation Area on the Crow Indian Reservation as an interpreter in their Visitor Center. Then I was asked to be the first unit manager at the Bear Paw Battlefield near Chinook, Montana. This was the opportunity I was waiting for, because this site, like the Big Hole National Battlefield, was all Nez Perce stories and the Nez Perce War of 1877. From there I was promoted to Idaho unit manager for the Nez Perce National Historical Park—again, protecting Nez Perce sites on my homeland.

I was content until I was recruited by Gerard Baker to be his tribal liaison for the Lewis and Clark National Historical Trail, where my main responsibility was to get the Indigenous tribes to talk about their encounters with the Corps of Discovery of 1805–06. Easier said than done. Many tribes, including mine, were not happy to remember this history. But it led me to encourage them to tell our side of these encounters. Through the years, it has been Anglo ethnographers, anthropologists, etcetera, telling our stories. I realized that’s what I was doing all along: telling our side of the stories.

This concept was so easy to understand, it is amazing how much pushback I received from some of the older Anglo individuals within the Park Service, the Old Bulls. But in Santa Fe, as tribal liaison for the National Trails System, then as the tribal liaison for our Washington, D.C., office, I was gaining allies. I used to point out to the Old Bulls that they spent big bucks on non-Indian “Indian experts” to give presentations, but they expected the tribes to do it for free. This was not right. Some of those Old Bulls said I was an AIMster—a member of the American Indian Movement—but I knew it was time for a change.

During my career, and whenever I went to training, I kept in contact with other Indigenous Park Service employees, and I put together a mailing list I called the NPS Tribe. I knew I was stepping on toes when an older Indigenous employee told me to remember who paid me. But I was American Indian first, National Park Service second.

One of the biggest challenges in all of this was getting the Park Service to say that almost all its sites have a tribal story. These stories should be told, the good and the bad. In some cases, traditional lands were taken and the tribes had to fight just to enter and gather medicinal plants for the people. Tribal consultation was needed, and listening sessions had to be initiated with the impacted tribes. My argument to the superintendents was that the sites had rich stories; including the tribal stories would make them even richer.

I had successes, but I also had my losses. The Park Service is an institution that has a hard time with change, and its history of working with tribes has a lot to be desired.

Ultimately, I reached out to other Indigenous employees, and we started the Council of Indigenous Relevancy, Communication, Leadership, and Excellence (CIRCLE). We had the support of some powerful members in the National Park Service in Washington, and these allies got us limited funding to start. Our idea was that if we were going to create change in tribal consultations, we must start with early-career professionals and win them over. These individuals would be the future superintendents. CIRCLE is still going strong, and I am pleased to say that it will continue on in the 21st century.

I encourage tribal people to work for the National Park Service. The Green and Gray is not so bad! You will see some beautiful country and have the opportunity to experience new adventures. You’ll have the opportunity to tell our story and that we are still here.

“I worked hard to tell a complicated story. Even when I was off the clock, I was still thinking of how to add to the story of my park.”

My name is Roger Amerman. My Indian name is Aba Cha Ha (High Above). I’m an enrolled citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. I live on the Nez Perce Reservation of Idaho—my wife’s community—but I was raised in Phoenix, Arizona; Portland, Oregon; and Pendleton, Oregon. I graduated from Pendleton High School.

In the 1980s I worked for the National Park Service on a contract basis as a science technician doing scientific avian and botanical surveys on the Little Bighorn National Battlefield. In 2015, the Park Service aggressively recruited me to be an interpreter at the Whitman Mission National Historic Site near where I grew up.

My professional title was Park Ranger, Interpretive Staff. My primary responsibility was to convey, in a balanced manner, the complex pre-statehood history of early 1800s missionary work among Cayuse Indians in the Inland Northwest , the history of early British and American trading companies in the Pacific Northwest, and the lifeways and attitudes of the Cayuse Indians. I was tasked with telling about the complex events that led in 1847 to tense, resentful, and angry Cayuse Indians killing Marcus and Narcissa Whitman at the mission they established on the Oregon Trail. Those events include the exposure of Cayuse peoples to disastrous American pandemic diseases, and to condescending and righteous missionary rhetoric and attitudes. Early colonial encroachment in the Inland Northwest caused dramatic engagements and changes to Native American lifeways. The result was terrible and violent and ended with a proud, free horse culture—the Cayuse peoples—being under siege and aggressively subdued, followed by the quick organization of statehood for Oregon and Washington.

It is paramount and respectful that the voices or narratives of the deceased Native ancestors be heard by the American public and understood. We insult visitors by telling biased, one-sided, mythical renditions of history. As National Park Service interpreters, we are conveying the soul of the nation—a sacred responsibility.

Historically, the National Park Service often told stories strongly anchored in the perceptions and experiences of colonial peoples and their descendants. In reality, the full stories—especially ones that involved Indigenous peoples—are often very difficult and much more complex. Thus, the Native American or minority story was until recent history usually diminished to be a backstory to the grander colonial narrative. In the last 25 years, the National Park Service has tried to tell a more balanced version of American history and the Native perspective. Most of the time, however, the new story is still told by Park Service employees who are colonial descendants—not deeply involved in Native American culture, perhaps not motivated to engage the Native story to the same degree, and challenged to convey a thorough and accurate Native perspective. I think Native interpreters steeped in their own tribal cultures are inclined to go the extra mile to educate the public about other vantage points of an historical event or issue

Native employees have developed strategies and tools to convey the history of Native peoples, tools and strategies non-Native employees may never have learned. Diligent Native American employees can provide the depth of commitment required to try to tell a very complex story and history accurately. Employment in the National Park Service can also be a very transient affair. I don’t think a lot of Park Service employees stay long enough at any one site to really learn the Native story or engage with contemporary Native descendants and find out their perspective. People are busy aspiring to transfer to another park where the grass is greener.

Interpreters are also charged with telling the story of the modern-day descendants of historical communities, and their status and state of affairs in current times. The history of their ancestors, good and bad, has a profound influence on modern communities’ status. It is not easy for non-Native Park Service employees to research these topics or engage with contemporary Native American communities. It is easier to let it slide.

When I think of a highlight from my experiences, what comes to mind is a partnership with the Pendleton Round-Up staff. It brought together National Park Service employees from the Whitman Mission National Historic Site and Nez Perce National Historic Monument and the members of the Umatilla Indian Reservation—people from the Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Umatilla tribes. With the help of a very supportive superintendent, I was instrumental in coordinating the one and only time my park was actively involved and highlighted at the world famous Pendleton Round-Up, which is well attended and includes more than a dozen tribes from the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia. Plus, it was in my hometown! We were in a very positive modern-day setting, engaged with the descendants of Cayuse peoples. I felt it to be an historical timeline of sorts.

For obvious reasons, telling the American public and Christian community about the mixed and hard effects on tribal peoples of Manifest Destiny, early missionary work with the Indians, and aggressive and destructive elements of American colonialism is not ever easy. I felt I had a lot of depth to add to the National Park Service and my park. I did not, however, feel that some of my co-employees valued my ideas and efforts to go the extra mile in conveying the story of our site. This could be very disappointing. I am highly educated, I am very knowledgeable of the American and Native American history of southeast Washington and northeast Oregon, and I worked extremely hard to tell a complicated story. Even when I was off the clock, I was still thinking of how to add to the story of my park.

Yet I’ve experienced a variety of professional opportunities in my life, and working for the National Park Service Interpretive Program is the most memorable and fulfilling. I would recommend the Park Service professions to any Native American who is an enthusiast of history, rural areas, natural resources, scenic beauty, and engaging the public. If you like working with Native peoples, many of our western parks are adjacent to or near Indian reservations and other Native communities.

As a ranger with National Park Service, I met people from every state in the United States and from countries all around the world. Our National Parks are remarkable—respected, treasured, and valued worldwide. True gems in this United States.

“Our ancestors have entrusted us with the duty to protect the lands that make us who we are and define our past, present, and future.”

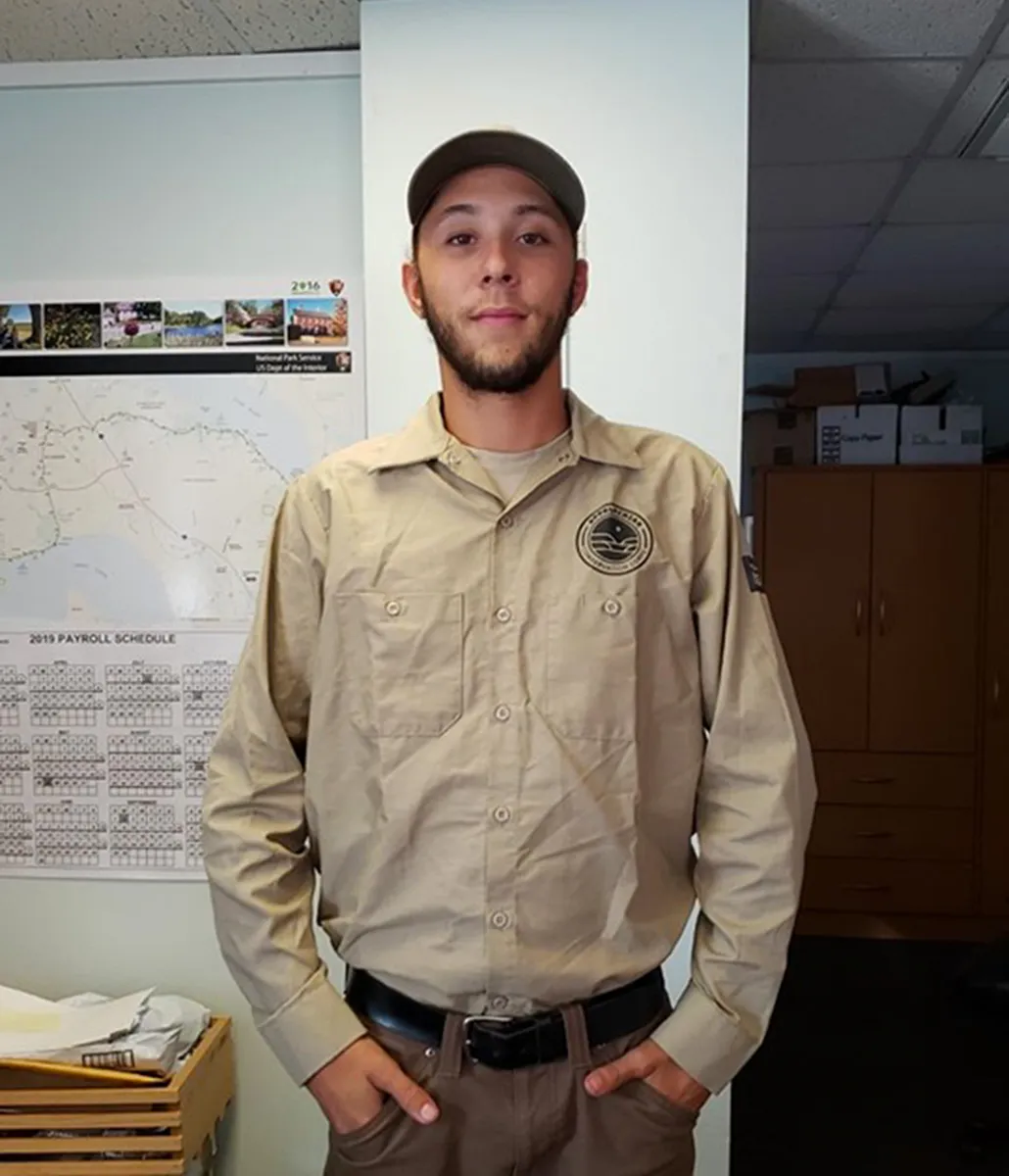

My name is Connor Tupponce. I come from the Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe in King William, Virginia, as well as the Chickahominy Tribe in Charles City, Virginia. I was raised in Glen Allen, Virginia, and I currently live back in my tribal community in King William, Virginia.

I have been longtime friends with Cindy Chance from the Captain John Smith National Historic Trail. She advised me of an internship with one of my tribe’s sacred sites, which is now part of the National Park System. I am a Werowocomoco Ancestral Lands individual placement intern, currently working out of Colonial National Park at Jamestown and Yorktown, as well as the Captain John Smith National Historic Trail at the site of Werowocomoco.

I believe it’s important for Natives to work on Native sites, because it allows full transparency from the Park Service side for area tribes to see the day-to-day operations of their historical and sacred sites. It is more important that we as Native people look after these sites, because our ancestors have entrusted us with the duty to protect the lands that make us who we are and define our past, present, and future.

A very vivid memory that will always stick with me from my time with the Park Service is my first experience at Werowocomoco. The power and strength I drew from being on the site, knowing its history Chief Powhatan’s headquarters during his encounters with the English colonists at Jamestown and its spiritual significance to my family, will be a feeling I could never forget.

My biggest challenge within the National Park Service so far has truly been not getting caught up in the moment while on site at Werowocomoco or Jamestown. It is very hard to stay on task when you’re a person like me where, most days, I will be looking around, imagining all the history of these sites.

To other Natives interested in this kind of career, I would say that it is such a great opportunity to visit, protect, and oversee plans for our own traditional lands that are protected within the National Park Service. It is such a unique workplace where, on my end, it is education, more than work. Native people in the National Park Service are working to guard what our ancestors fought to build, and it is our duty to carry on that legacy and educate others on our perspective on national parks.

I am very grateful to the National Park Service as well as Conservation Legacy and AmeriCorps for allowing me, in this internship, to oversee my tribe’s sacred site in a way where I can learn as well as educate others.