NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

Educator’s Blog: Land Acknowledgments as a Tool Towards Social Justice in Your Classroom

Teaching about Land Acknowledgments in Your Classroom or Community

Have you heard about land acknowledgments but wonder what they are? Today, land acknowledgments are used by Native peoples and non-Natives to recognize Indigenous peoples who are the original stewards of the lands we live on. Land acknowledgments are mostly used in the (now) Americas, Australia, and New Zealand. Land acknowledgments can be written or spoken and are presented at the beginning of important events.

Land acknowledgments are not new to Native people. Native nations from throughout the Americas have, for centuries, practiced different ways of acknowledging land ownership. In the Pacific Northwest, Native nations would visit their neighbors on canoes, announce themselves from the sea, and ask permission before coming ashore. They often brought gifts and food items to establish good relationships with the home community. This protocol recognized the land tenure and stewardship of different Native nations and still occurs throughout the Pacific Northwest today. This centuries-old practice of respect is echoed differently throughout many Native nations.

Today, land acknowledgments provide an opportunity for people of any ancestry to gather and recognize the rich history and culture of the land’s Native nations and the home that we now share. They start by telling a more complete truth about colonial history and recognize that we are (mostly) uninvited guests on this land. Colonialism, government policies—such as broken treaties—and settlers took land that belonged to Indigenous people of the Americas. These histories are still visible today and many times prevent Native people from stewarding their ancestral lands. Land acknowledgments are a first step in recognizing this history and can begin to shed light on how your role today could support past injustices. They present a more honest history that includes—and even privileges—Native American perspectives, values, and systems of knowledge that might support ways of living that are sustainable and equitable for everyone.

Why do we do them? They can be a moment to come together and to recognize the land we live on. While everyone is encouraged to participate in the honoring of a land’s history, it can be particularly significant for Native people, especially kids, to hear their tribe's name and heritage acknowledged by others. Native people were deeply rooted to their homelands for thousands of years, learning how to become stewards of the land and building spiritual connections with the environment. A culture’s customs, food practices, burial grounds, sacred sites, art traditions, and even language are tied to the land. A respectful recognition of that ancestral relationship can be powerful for Native people to hear. In an educational setting, where new ideas are fostered, teachers giving land acknowledgments can be a powerful way for Native American kids to feel “seen” and recognized as the original peoples of the United States.

A growing number of school districts, historical societies, museums, and even yoga studios are adopting land acknowledgments and committing to the important work required to establish them. How can you help to ensure that they aren’t just part of a trend and play an active role in this movement towards more meaningful social or environmental justice? Here are eight ideas or key concepts to use in crafting acknowledgments that honor Indigenous peoples and this land we call home.

Begin where you are

Land acknowledgments start with first acknowledging that we all live on land that sustains us. They begin by honoring the land and waters, the many wondrous creatures, and all that Mother Earth gives us. In my tribe, I was taught to thank the land I am standing on to begin with. From there, we thank different elements in the natural world, sometimes with particular emphasis, depending on our clan. Like many Native peoples, the Haudenosaunee (a confederacy of six tribes) have a rich and ordered way of thanking the elements and each tribe often calls upon its own traditions and language. Read the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address - Greetings to the Natural World (si.edu). Take responsibility for your own backyard, for nearby community spaces, and local public lands or national parks. Build reciprocity with the land. Advocate for using more native plants and trees that provide oxygen and homes for insects, which in turn provide food for birds and are crucial to saving ecosystems! Do creek cleanups, join the homegrown national park movement (HOMEGROWN NATIONAL PARK), or create “butterflyways.” Devise strategies to defend the land and water by spending time there, deepening your relationship with it, providing voice to its protection, and ultimately sowing seeds of hope and beauty for future generations.

Cultivate your own learning

First, you need to know who to acknowledge as the original stewards. If you do not know where to start, I recommend the website Native-Land.ca | Our home on native land, which is a Canadian, Indigenous-led not-for-profit organization. After familiarizing yourself with local place names and learning about Indigenous groups in your community, you may want to reach out to local tribal museums or libraries. After all, Native people are the best source of Native perspective, and you can learn a lot from tribal members in your region. However, if you cannot receive individual guidance from a Native citizen in your area, there are other ways to learn from and support them. Land acknowledgments can play a role in enhancing awareness and developing supportive and respectful relationships with the Native people of the land. If you wish to incorporate a land acknowledgment into a school setting, you may start by having students do the research into their neighborhood, school, or town. It’s okay if, as you dig into the research, you generate more questions and curiosity with your kids; they can have a role in uncovering what might be “hidden history” around them. Further, you might establish a Native advisory group in your school, have representation on the PTA and bring in Native presenters to speak about Native topics, or facilitate a session for school administration and teachers to listen to Native parents.

Seek Indigenous perspectives

Almost every Native nation has an easily accessible website with information on their history and culture, current language revitalization activities, education efforts, and how they work to protect and maintain their lands. On these websites, you can usually find valuable information about a Native nation, told from their own perspective, as well as news about current events that are important to their community. Read Native-authored books, such as An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, and read poetry that connects you through emotion and imagery. Joy Harjo (Muskogee) is the current poet laureate for the United States! Explore her work through this Library of Congress website: Living Nations, Living Words | Poet Laureate Projects | Poet Laureate | Poetry & Literature | Programs | Library of Congress (loc.gov). Also, turn to primary sources such as quotes, photographs, and articles that are part of NMAI’s national education initiative, Native Knowledge 360˚, at www.nmai.si.edu/nk360. These can be accessible ways for you and your students or community to learn from and understand Native people and perspectives.

Our history doesn’t begin with Columbus

Land acknowledgments refer to people who lived in a particular place at the time of European arrival in the Western Hemisphere, but that is not where Native history begins. American Indians have lived on this continent for at least fifteen to twenty thousand years. Despite what the textbooks say, many of us do not subscribe to the Bering Strait theory taught in many schools. Unfortunately, it is still not presented as just one theory alongside others. What’s more, there is often no mention of new research that places Indigenous peoples in the Western Hemisphere much earlier than originally suggested. We have our own stories of how we emerged as a distinct people and who we are. As you dig into local history, work towards putting specific groups of people in a time period and know that history is complicated and became more so with the influx of thousands of people and new governments who sought Native lands and forced changes upon the people. History is messy and it’s okay to uncover more questions and leave some unanswered with your kids, students, and friends as you seek to understand more and think like historians together.

Speak with care

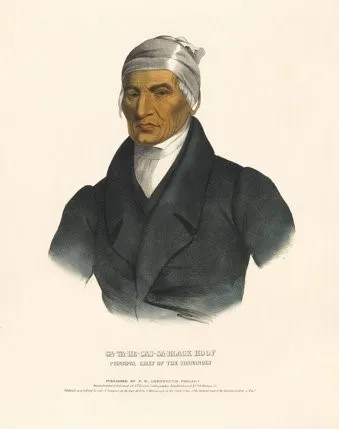

Be aware that names change over time and that the name a nation is using may be different from the name they are most commonly known by or that colonizers gave them. For example, the Pueblo Ohkay Owingeh (formerly San Juan Pueblo) is a name that reflects the tribe’s history and interaction with the Spanish in New Mexico. In my tribe, the Shawnee, we call ourselves Shi-wi-ni, which means “warm or moderate weather people,” a name that tells more about who we are and is an important identity marker as some of us relearn our language and teach it to younger generations. A lot of tribes are reclaiming their original names and you should always strive to use those in land acknowledgments or in other materials that you create. For guidance, use The Impact of Words and Tips for Using Appropriate Terminology | Helpful Handout Educator Resource.

History is ongoing

When writing your acknowledgment or referring to Native peoples, begin with the understanding that Native people are still here today. American Indian history is one of cultural persistence, creative adaptation, renewal, and resilience. Native individuals, groups, and institutions continue to resist oppression and protect heritage. Native people can speak for themselves, so be careful never to speak for or represent Indigenous communities. Instead, seek out their diverse voices. Write in the present tense when writing about Native nations. If you need to refer to historical Native groups in the past tense, it is important to always provide context to the time you are referencing. Otherwise, you may be misrepresenting present-day Native cultures as no longer existing. In fact, it is very likely that Native people live in your community on the land you call home today. Native people are our neighbors in the suburbs, on reservations and rural areas, and especially in big cities. There was actually a 1956 U.S. law intended to encourage American Indians to leave reservations or traditional lands to assimilate into the general population in urban areas.

Build relationships

Support Indigenous peoples by lifting the burden of education off of their shoulders. Check out the videos and websites listed below to learn about the Land Back movement, which has existed for generations and advocates for Indigenous rights in land governance. See: What Is Land Back? - David Suzuki Foundation. Learn more about a recent Land Back campaign that officially launched on Indigenous Peoples Day, October 12, 2020, and seeks to dismantle white supremacy and systems of oppression. Their goal is to coordinate efforts to put public lands back into Indigenous hands and build a movement for collective liberation.

Keep going

Know that land acknowledgments are a first step in creating collaborative, accountable, continuous, and respectful relationships with Indigenous nations and communities. Do not stop with a land acknowledgment and consider that you’ve “done your part.” True reconciliation and relationship building requires ongoing effort and practice. If you are a teacher, strive to build a classroom dedicated to social justice by consulting programs such as Teaching for Change - Building Social Justice Starting in the Classroom and NMAI’s Native Knowledge 360˚ initiative, www.nmai.si.edu/nk360. Be sure to peruse the wonderful list of social justice books for young people here: Multicultural and Social Justice Books - Social Justice Books. Make continuous efforts in your classroom and home to ground yourself in learning beyond the textbooks. Take active steps to care for Indigenous land, and know that the work you do matters toward building a more equitable and just society for humans and our relatives in the natural world.