NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Narwhals, Narwhals, Swimming in the…Smithsonian?

Take a behind-the-scenes look at the development process behind the new exhibition, “Narwhal: Revealing an Arctic Legend” on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

:focal(744x276:745x277)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/NHB2017-00987_2_cropped.jpg)

It’s almost spooky inside the Smithsonian’s Museum Support Center in Suitland, Maryland—shadowy and silent, except for the ever-present humming of the ventilation system maintaining a precise temperature and humidity. Lights are kept low or off until they’re needed, to protect the specimens stored here. Inside this football-field-length “pod” (one of five), massive metal shelves reach nearly to the ceiling. And here, in the area reserved for the whale collection, are row upon row of ribs, vertebrae, skulls the size of cars, and other whale parts. As the content development team for a new exhibition on narwhals at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, we’ve come here to see the fabled narwhal tusk up close.

Narwhals are toothed whales that live only in the Arctic and are uniquely adapted to move, breathe, and feed among sea ice. Their tusks conjure images of the unicorns narwhals may have helped inspire, and raise many questions: What does that tusk do? Why did it evolve? And why are narwhals still so mysterious?

Why a Narwhal Exhibit?

Narwhals are having a moment. New research into tusk function and feeding strategies have brought this elusive animal into the news, while declining sea-ice cover has drawn new attention to its Arctic ecosystem. While the world narwhal population is currently stable at around 173,000 individuals, climate change in the Arctic may pose the narwhal’s biggest threat.

Blame or thank the catchy “narwhal song” that went viral in 2015, but narwhals’ cool factor seems undeniable. We saw great potential to build on narwhals’ unusual pop-culture cachet to educate visitors about narwhal biology, the people who depend upon them, and their fragile ecosystem.

First Things First

Every exhibition at the National Museum of Natural History begins with an exhibit proposal. Narwhal: Revealing an Arctic Legend came from curator Dr. William Fitzhugh and research associate Dr. Martin Nweeia, who are experts in Arctic cultures and narwhal tusk research, respectively. After approval by Museum officials, the exhibition got its core team: the people who take it from concept to reality. The core team included the content experts, plus a project manager, a designer, educators, fabricators, and an exhibition writer (that’s me).

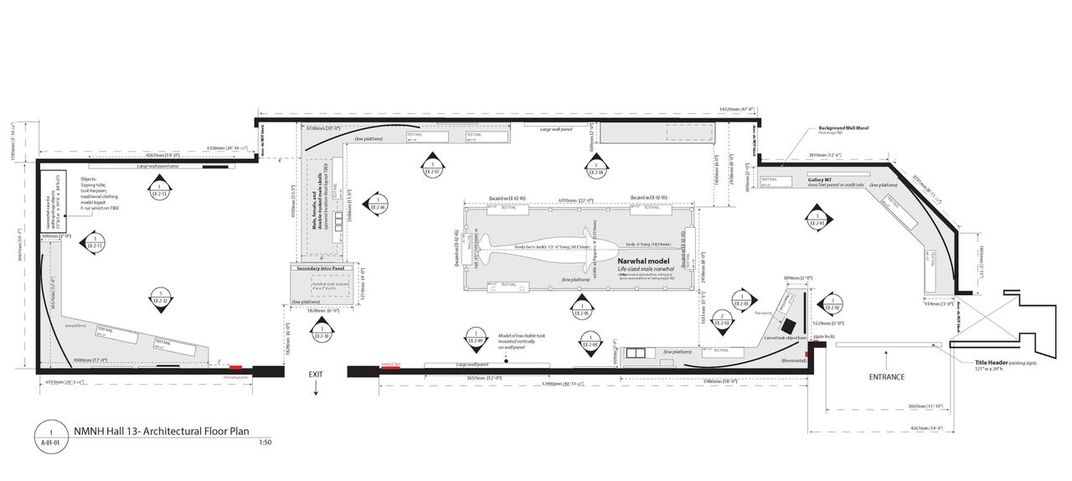

We began working on the exhibition in spring 2015. We carefully considered the physical space we’d have, and what needed to fit there. The exhibition gallery is a long, thin rectangle, and exhibit designer Kim Moeller knew she needed to leave plenty of room for the star of the show: a 13.5-foot, life-sized model of a male narwhal with a six-foot tusk.

Moeller also wanted to highlight breathtaking panoramas of the Arctic, so she designed several walls within the gallery to feature large-scale landscape images, plus maps created by Smithsonian cartographer Dan Cole. And then there were the tusks—including two that belonged to a remarkable, rare, double-tusked skull.

Our advisers—marine mammal specialists, narwhal genetics experts, liaisons to Inuit (indigenous Arctic) communities, and climate-change scientists—weighed in with advice and concerns as we developed the exhibition outline.

Welcome to Pond Inlet

From the earliest days of developing Narwhal, we wanted the deep involvement of the Inuit—the people who know the animal best. Content curator Martin Nweeia introduced the team to Pond Inlet, an Inuit community of about 1,600 people on the northeastern edge of Baffin Island in Nunavut, Canada.

We set up phone interviews with some Pond Inlet community members to learn more about their lives and the narwhal’s significance in them. During our phone calls to the Arctic, I made an intensive effort to spend more time listening than I did talking. I tried to be especially conscious of not paraphrasing what I thought the community members were suggesting when they paused during our conversation. I wanted to make sure all had the time and space to tell their stories at their own pace.

To avoid the pitfall of “mythicizing” or insensitively portraying Inuit culture, core team members had a debriefing with Smithsonian anthropologist Stephen Loring, where we discussed appropriate language usage for the exhibition text. A word like “village,” for example, sounds innocuous. But it can carry unintended connotations of primitiveness or underdevelopment. That’s why “community” is a better choice when writing about indigenous people’s homes.

Throughout exhibition development, our Pond Inlet collaborators weighed in on our content, providing critiques and suggestions. One particular highlight was a visit from two Pond Inlet residents to the Museum—Elder, hunter, and Pond Inlet mayor Charlie Inuarak, and his son, hunter Enookie Inuarak.

What Happens in the Arctic…

…doesn’t stay in the Arctic, unlike Las Vegas. Climate change in the North has far-reaching, global effects on animals, on food stability for humans, on weather patterns, on shipping, travel, and energy production, and on geopolitical relationships. The Narwhal exhibition team wanted to keep this message at the front of our visitors’ minds.

Our experienced colleagues from the exhibitions and education departments at the Museum advised us on our approach to climate change in the exhibition. They cited research about climate-change education, reminding us that often the public “tunes out” talk of climate change or global warming because the topic is so widespread in the news media. In addition, the statistics are uniformly grim, which can lead to feelings of hopelessness, despair, and “shutting down,” rather than the discussions of innovation for change that we wanted to inspire.

We decided to tie our climate-change content very closely to narwhals themselves—to draw our visitors’ interest, and to emphasize the interconnectedness of climate change to the species and people that live in the Arctic.

Science in Progress

Increased narwhal research means new discoveries seem to be happening all the time. In May 2017, we got some exciting news from Dr. Marianne Marcoux, one of the exhibit team’s content curators and a narwhal research scientist. She and her colleagues at Fisheries and Oceans Canada had used a drone flying close to the water to capture footage of a narwhal appearing to “stun” fish before eating them by hitting them with the tusk. While Inuit hunters had reported this behavior before, it had never been documented on video.

We wanted visitors to have access to the most up-to-date science once the exhibit opened, so we worked quickly to update the exhibition text, and to add the fascinating footage to a short video in the exhibit about the importance of Inuit traditional knowledge in guiding science.

Putting it All Together

Fabricator Jon Zastrow and the exhibit production team built three new cases for the exhibition, while modifying three existing cases to display Inuit-made objects like a hunting visor, parka, and narwhal-ivory tube for sipping melted water. Graphics, lighting, and audio-visual specialists printed the panels, designed and installed the exhibition lighting, and perfected the video and soundscape presentations.

All told, it took 28 months from the Narwhal exhibition kick-off meeting until the day the exhibition opened for the public—about twice as long as the narwhal gestational period. The continued, complex environmental changes underway in this region will bring uncertainty in the future. We hope the Narwhal exhibition opens our visitors’ eyes to the interconnectedness of Arctic ecosystems, marine mammals, and the people who rely upon them.

Special thanks to the other members of the exhibition core team: content experts Bill Fitzhugh, Martin Nweeia, and Marianne Marcoux; project manager and exhibit developer Christyna Solhan; designer Kim Moeller, and educators Trish Mace and Jennifer Collins, and to all the members of the Museum’s fabrication, audio/visual, and production teams.